Alternate format: Public content provenance for organizations - ITSP.10.005 (PDF, 1.0 Mb)

Overview

This publication is intended for security and public communications practitioners. It lays the foundation in explaining what public content provenance is and why it's an important tool for organizations to establish a verifiable historical record of the content they make available online. It provides information about the range of technologies which help to establish trust in digital records along with examples of how they might be used to meet different requirements.

This publication has been jointly researched and co-authored by the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) and the United Kingdom’s National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). The Cyber Centre and the NCSC do not directly endorse the products, services or methodologies in this publication. The tools and standards described are a means to demonstrate how to improve cyber resilience in different contexts using combinations of technologies.

Table of contents

- 1. Securing trust in digital content: Why public content provenance matters

- 2. The challenge of securing digital trust in today’s complex information environment

- 3. Provenance: Selecting suitable systems and technologies

- 4. Deploying public content provenance systems: Considerations and example use cases

- 5. Next steps

1. Securing trust in digital content: Why public content provenance matters

In today's digital age, information on the Internet cannot be relied on consistently as a source of truth. The rapid rise in the volume of available information and the accelerated pace of content generation, particularly through Artificial Intelligence (AI), mean the Internet has become a battleground for interference and malicious cyber activities.

In this environment, organizations are finding it increasingly challenging to ensure the authenticity and integrity of their information. As such, they must rethink how they establish and maintain trust with their audiences. As highlighted in the NCSC’s Impact of AI on cyber threat from now to 2027 and the Cyber Centre’s Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process: 2025 update, AI-enabled capabilities continue to proliferate to cyber criminals. States are beginning to integrate AI-enabled technologies into their cyber capabilities. Organizations will therefore need tools to improve their resilience and security to protect the integrity of data and information. A cornerstone of these efforts is the establishment of provenance for digital content.

Provenance refers to the place of origin. It is used in the physical world to verify the authenticity of artefacts, but it is also relevant in the online world. Many organizations already employ versioning and logging systems to establish provenance for internal documents. However, these systems are often useful only within the organization. To build stronger trust with external audiences, organizations need to improve how they address the public provenance of their information

2. The challenge of securing digital trust in today’s complex information environment

Today’s information environment comprises a wide variety of forms of communication, ranging from traditional media and social media to telephone conversations and even signs on lampposts. This makes it easy to access large amounts of information quickly. Different processes within this environment collect and reorganize data and metadata to meet the needs of various groups such as information seekers, publishers and advertisers. Additionally, social media platforms enable widespread republishing and the option to add commentary.

Although the information environment benefits both content creators and consumers, it also presents challenges. An original piece of content may be collected, reorganized, summarized, aggregated, reformatted, republished and modified throughout its lifecycle. Modifications may be made deliberately or otherwise, and with or without intent to deceive. These modifications can be difficult to detect as the information rarely persists in its original form. This means we cannot be certain that the intended meaning of the content is retained. Or worse, that it has been distorted.

For security practitioners, protecting information in this environment poses significant challenges. They have traditionally focused on protecting the confidentiality, integrity and availability of digital data directly controlled by the organization but now must also focus on protecting publicly available information about their content, which is outside of their control. To address this, organizations can use public trust mechanisms to verify the source and history of content.

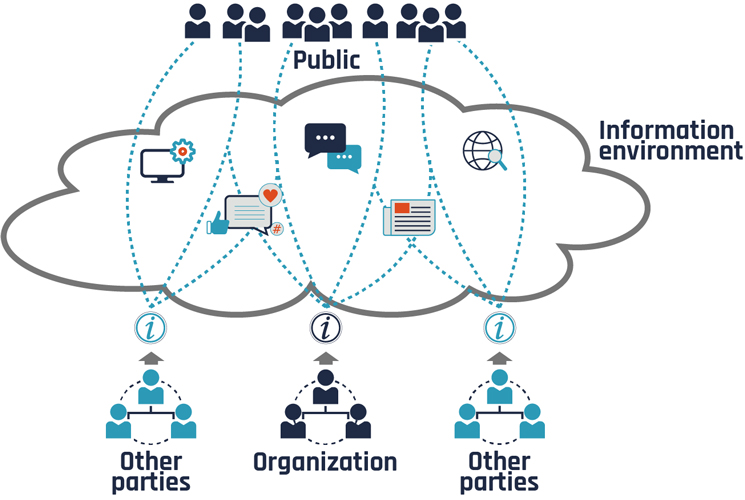

Figure 1: Communicating an organization’s information in the information environment

Long description - Figure 1: Communicating an organization’s information in the information environment

To communicate with the public, organizations share their information in the information environment. This environment comprises all forms of communication between the organization and the public audience and can include social media, content aggregation sites, web search services, traditional media such as radio and television, as well as others. Other parties can add to the communications with their own content in the form of comments, selective filtering and so on. The overall message that a member of the public audience receives or accesses may not be what is intended by the originating party. It may not even be accurate.

2.1 Digital content provenance explained

The term provenance is defined as the “place of origin” and is used as a guide to the authenticity and quality of a given artefact. It is traditionally used in the context of art and history. In digital environments the concept can be applied in many ways to deal with specific challenges in domains such as Internet content history, supply chain integrity, data management, software certification, scientific process management, financial transactions tracking as well as legal chain of custody management. Each has its own unique requirements.

The focus of this publication is public content provenance. Content provenance provides factual information about the history of digital content without making assertions about the value or truth of the content itself. Decisions on the veracity of the content are left to the consumer, but additional verifiable information is provided to aid them in making a final determination. Content provenance can provide different types of verifiable information including, but not limited to the following:

- individual or entity making a claim about the content

- date and time of a claim

- image against its verified thumbnail

- claims such as location, device or edits made with software

- statements about whether the work is creative or AI-generated

- assignment of rights to others (for example, via Creative Commons or other public copyright licenses)

By clearly establishing the facts about the history of its public digital content, such as its origin, authenticity and quality, organizations can build better trust with their audiences, customers and stakeholders.

2.2 Digital content provenance analogy

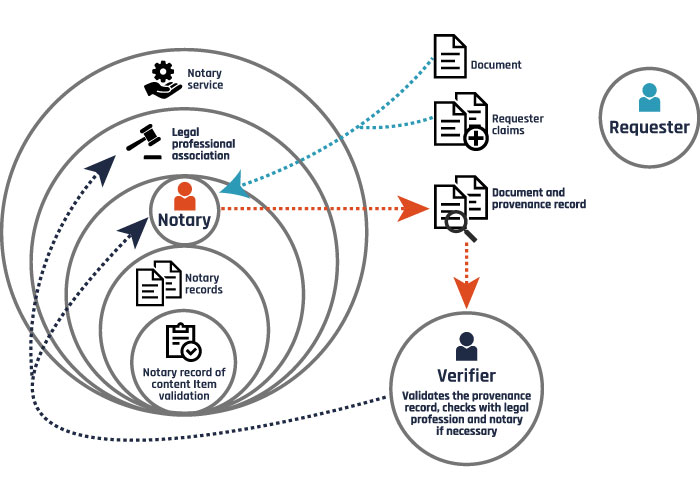

A good analogy for provenance is that of a notary. Many legal systems employ the concept of a notary to witness signatures as part of legal proceedings. The notary is a trusted third-party who performs the witness activity in a way that is acceptable for legal requirements.

Members of the public who need documentation for legal requirements visit the notary, who confirms their identity and ensures they are signing willingly. The notary then attests to the content of their documentation, as well as the date and time the attestation was done. This attestation involves a formal declaration that the document is genuine and the signatures are valid. Notarized documents are legally recognized and can be used as evidence in court.

In a similar way, digital content owners use an attestation service to verify the details of the content, such as hash or thumbnail image, and establish verifiable evidence such as the location, time, and the notary details. This is done using cryptographic methods rather than paper documents.

Additionally, just as notaries maintain a ledger of all notarised documents, attestation services can record their attestation transactions as part of their service. The basic public notary function is illustrated in figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Notary function as analogy for public provenance

Long description -Figure 2: Notary function as analogy for public provenance

The notary function serves as an analogy for public provenance. Many jurisdictions employ notaries to act as third-party validators of documents to be used for legal purposes. The requester submits their documents to the notary and indicates their claims. The notary validates the documents as well as the claims and provides a formal record of attestation such as a stamp or document to the requester. The notary records their actions with the requester in a record register. The requester can provide the notary’s record of attestation to any verifier. The verifier, commonly the court, can also check with the notary to validate that the attestation was done. They can also check with the legal professional association as to whether the notary is licenced to perform the notary function.

2.3 How to earn trust in digital content

To establish why organizations need to consider public provenance, it is useful to understand the broader digital trust context. The issue of trust on the Internet is not new, and it was an integral part of the development of e-commerce.

A major objective for organizations is to establish trust with their audience, customers or stakeholders.

The World Economic Forum’s 2022 report describes the following 8 dimensions of trust for digital technology. These factors are important for information assurance more broadly.

- Cyber security: mitigating the risks of both malicious and accidental uses of technology

- Safety: preventing harm (for example, emotional, physical or psychological) to people or society from technology uses and data processing

- Transparency: establishing visibility and clarity around digital operations and uses

- Interoperability: ensuring information systems can connect and exchange information for mutual use without undue burden or restriction

- Auditability: ensuring that organizations and third parties are able to review and confirm the activities and results of technology, data processing and governance processes

- Redressability: providing the possibility of obtaining recourse where individuals, groups or entities have been negatively affected by technological processes, systems or data uses

- Fairness: ensuring that an organization’s technology and data processing considers the potential for disparate impact and aims to achieve just and equitable outcomes for all stakeholders, given the relevant circumstances and expectations

- Privacy: ensuring that individuals have control over the confidentiality of their personal or personally identifiable information

Most organizations today address these 8 dimensions to some degree, but digital trust requirements are evolving as the Internet matures. These requirements are also driven by changes in how people behave on the Internet and advances in AI.

2.4 How digital content provenance helps enhance public trust in an organization

Content provenance can help to address and enhance the digital trust in an organization in a number of the above 8 dimensions, including the following:

- Cyber security: It helps verify that content is sourced from legitimate and secure origins, which reduces the risk of malicious content. It also helps with maintaining immutable records of content creation and modification to prevent unauthorized alterations.

- Safety: It can reduce the impact of inaccurate information about individuals and organizations. The verifiable provenance record can aid in refuting inaccurate online information.

- Transparency: It establishes verifiable metadata about the content itself. This metadata helps establish a content item's history, including creation and handling. The public availability of this information makes the content and related processes more transparent.

- Auditability: It establishes a digital content record as well as the means to verify it. This can be used in auditing programs.

- Fairness: It establishes a formal verifiable record of information about content. This can include information about the creator, ownership, and rights for digital content. This verifiable information can be used to adjudicate any issues around content rights and validity.

Content provenance provides the public with a means of assessing the accuracy of content created by or related to an organization. This can enhance the trust the public has in an organization.

3. Provenance: Selecting suitable systems and technologies

The subject of content provenance isn't entirely new but advances in technologies, such as generative AI, are driving requirements for it to evolve even faster.

Frameworks which offer ways of structuring provenance systems are still being established.

There are multiple facets to the provenance challenge which will require different approaches. One approach may not necessarily solve all of an organization’s content provenance requirements. Some examples of the current provenance challenge include synthetic media labelling, provenance of digital source media, deepfake detection, and provenance of aggregated content.

Organizations will have to identify a framework relevant to their needs. The key aspects to consider when selecting a framework include:

- how trust in the provenance record is established – does it use cryptographic methods such as trusted timestamps (see 3.2.1) and cryptographic identities (see 3.2.2) to secure integrity?

- how members of the public can verify provenance – are the mechanisms simple and understandable by the public in general?

Organizations will have their own content provenance requirements but should be mindful of the rapidly evolving requirements and standards in public provenance infrastructure. They should consider standards used in their specific solution to ensure provenance functionality, such as verification work at scale.

In addition to choosing a provenance solution which meets its specific objectives, an organization will need to decide which technologies to use. This decision will be driven by organizational objectives as well as the availability of technology solutions.

3.1 What to consider when selecting provenance systems

Provenance systems vary in complexity, cost and effectiveness and organizations will choose their solution to meet their specific objectives. It is also important to consider that digital provenance technologies are in their infancy and that organizational requirements will inevitably evolve. For this reason, an organization may choose to implement partial or iterative solutions.

This section provides information on the aspects to consider when choosing provenance methods.

3.1.1 Source of trust

What is the source of trust for the content provenance record? Organizations may use internal services but will need to consider ways to mitigate the perception of "self-signing" the provenance record. This challenge can potentially be addressed by using third-party operators or auditors. Organizations will need to consider the reputation and stability of third-party organizations used for establishing the provenance record.

3.1.2 Extent of provenance record

How far back does the provenance record go? At a minimum, it should trace the content back to its publication date, and identify whether the information came from a real-world device or was generated by an AI system. Ideally, the provenance should be traceable all the way back to the creation of the original source material and include provenance information about other components it contains, such as images.

3.1.3 Ease of verification

How simple is it to verify the provenance of a content item? In most cases, the verifier will be a member of the general public. The verification mechanism must be simple to use and yield an easily understandable and accurate provenance record.

3.1.4 Cost of providing provenance

How much does it cost to provide the provenance record? The organization must be able to sustain the costs.

3.1.5 Strength of provenance claim

How strong are the provenance claims? Can facts about the identity and time claims stand up to scrutiny? Cryptographic validation by other parties can strengthen the claims and improve public trust in the content’s provenance record.

3.1.6 Duration of the provenance claim

How long will the provenance record need to exist? If it's in the range of years or decades, then consider the sustainability of both the content store and the verify mechanisms.

3.1.7 Utility of the provenance

How does the provenance mechanism aid in reducing errors or distortion of an organization's information? Does the mechanism aid the public in making decisions about the organization’s content? Other information correction measures may be more effective for an organization’s specific challenges.

3.1.8 Redress requirements

How is inaccurate information corrected? All countries have established legal mechanisms for responding to at least some inaccurate information claims against organizations in the form of libel laws. Most countries have laws in place to address copyright and trademark infringement issues. These and other laws can be used by organizations to seek redress for inaccurate information about them.

In some cases, such as copyright, there are very structured requirements for identifying infringing material and notifying hosting services to remove it, such as labelling and deploying automated processes for submission and response. Existing and potential future legal remedies and processes should be considered, as well as the cost and time required to use the redress mechanisms.

3.1.9 Privacy considerations

Can privacy of individuals be addressed? Identity of actors is an important provenance detail, but it is not always possible to use it such as where there may be risk to life, reputation or other concerns of individuals providing content. In some cases, it may be required by law to shield an individual’s identity.

3.2 What to consider when selecting content provenance technologies

In addition to choosing a provenance solution which meets its specific objectives, an organization will need to decide which technologies to use. This decision will be driven by organizational objectives as well as the availability of technology solutions.

Technologies that may be relevant for an organization include:

- cryptographic integrity mechanisms, such as public key infrastructure (PKI) identities, hashing and trusted timestamps, which can be used to bind together parts of the provenance solution to ensure the veracity and integrity of provenance records

- authentication for devices and software, individuals and trust anchors, which is an essential part of establishing accountability in the provenance record

- decentralised storage, which can help

- address the continuity challenges with content and records when organizations are eventually disbanded

- ensure that one party does not have full control over the digital content or ledger records

- tamper-proof ledgers, which address the challenge of permanence in the provenance record by creating records that are impossible to alter without a record of the alteration and are independent of the content

Consideration should also be given to which parties implement the various technologies, to maximise the trust created. Organizations that create or “self-sign” their own provenance record are unlikely to see improvements in the trust of their content.

3.2.1 Trusted timestamps

Trusted timestamps are a useful provenance mechanism in that they establish a trusted timestamp for content state. When implemented properly, no one should be able to change a timestamp once it has been recorded. This concept is standardised in the RFC 3161: Internet X.509 Public Key Infrastructure Time-Stamp Protocol (TSP) and American National Standards Institute Accredited Standards Committee X9.95 standard (ANSI ASC X9.95).

The mechanisms use cryptographic methods to calculate a hash of the document and the timestamp. A third-party organization generally performs the timestamping to improve trust in the mechanism. Commercial services are available to perform this function.

3.2.2 Cryptographic identity

Cryptographic identities are part of PKI. They are bound to a private cryptographic key known only to that entity. The identity can be an individual, an organization, a machine entity such as a device or service, or can be anonymous.

Cryptographic identities are commonly anchored in public certificate authorities. They can play an important part in content provenance since they can bind individuals and devices to content and assertions on content. This can strengthen the provenance of the content.

3.2.3 Digital ledgers (Blockchain)

Blockchain is a decentralised digital ledger technology that records transactions in a secure, tamper-proof manner. Each transaction, or block, is cryptographically linked to the previous one, forming a continuous chain. This chain of blocks provides a complete and transparent history of all transactions, making it virtually impossible to alter or manipulate without detection.

Blockchains are often implemented in a decentralised file system, meaning that they are not owned by any one individual or organization and they have no single point of failure. Organizations can use public blockchains or they may choose to use a more private implementation, depending on specific provenance needs.

The NCSC has published guidance on the use of distributed ledger technology to aid in determining whether distributed ledger is an appropriate technology for a given scenario.

3.2.4 Web archiving

Web archiving refers to the process of collecting and preserving digital content from the World Wide Web so that it will be accessible in the future, even if the content is removed from a website. The primary goal of web archiving is to create a permanent record of web content, capturing website evolutions and online information changes. This process is invaluable for the preservation of digital media provenance because it captures digital assets' original form, context, and ownership, as well as subsequent versions. The Internet Archive Wayback Machine is an example of a general web archiving service.

The web archiving approach can be expanded into a more robust provenance mechanism using cryptographic signatures and timestamps. The archived data can be used to verify the authenticity and integrity of digital content and establish its historical context.

3.2.5 Digital watermarking

Digital watermarking is not a provenance mechanism but is included here because it is often considered for addressing digital trust challenges. Digital watermarking can be overt or covert.

Overt watermarking entails adding a visible or easily detectable watermark to content such as images or video. It is often a pattern which the viewer can see. Editing the watermark will result in distortions to the image or video that may be detectable by the end viewer if unsophisticated editing changes are made.

Covert watermarking entails adding a watermark the viewer cannot detect to the content. It will become distorted if the image or video is edited. Distortions will not be readily detectable by viewers but will be detectable by those implementing the watermarks.

Overt and covert watermarks may provide a means of detecting some attempts at altering digital content. Many forms of overt watermarks can be removed using modern editing software. Covert watermarks are limited in effectiveness by the small number of parties that can detect changes. These considerations may therefore limit the usefulness of watermarks in addressing digital trust requirements. However, watermarking can still add value as part of a layered defence implementation.

3.2.6 The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity

The Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA) is an industry organization that aims to address the prevalence of misleading online information through technical standards. It has established an open specification for documenting and certifying the source and history of media content.

The Content Authenticity Initiative (CAI), which includes major technology and media companies, is responsible for promoting the C2PA standard. C2PA is a relatively new but major standard in the provenance space, and it is still under development.

C2PA leverages cryptographic methods to establish provenance on media content. This is organized around a manifest that is stored as part of the content. The manifest can capture information about changes to an item, including the author/editor, timestamp and location, and cryptographically bind it to the content. There can be multiple manifests stored in a manifest store reflecting the history of changes to the content. This manifest store is also known as a Content Credential (represented by the “CR” icon). The standard leverages trusted timestamps and watermarking.

3.3 Why private provenance systems aren’t suitable for public content

Most organizations have some sort of internal versioning and logging systems to track details of changes to content. These systems are private in the sense that the systems and supporting integrity mechanisms such as PKI certificate authorities are often internal to the organization.

A private provenance infrastructure works well for corporate and some legal requirements but is largely unusable for public provenance requirements. This is mainly because the mechanism is wholly managed by the organization and designed for restricted internal use only. Additionally, private provenance systems rely heavily on separation of duties as the main mechanism for integrity of records.

Private provenance systems lack the visibility, transparency and accountability features necessary to make their provenance capability useful for establishing public trust in an organization’s information. To address public requirements, organizations need to reconsider provenance mechanisms for at least some of their content.

4. Deploying public content provenance systems: Considerations and example use cases

Not all organizations will have the same requirements for public provenance of their content. Requirements depend on factors such as the organization’s:

- particular public information trust challenges

- overall strategy for addressing public information trust

- audience

- volume of content

- financial resources

Specific requirements may evolve quickly given the rapid changes in the information environment driven by cyber criminal and state use of AI.

4.1 Points for organizations to consider

When considering deployment of a public content provenance system, there are a number of questions organizations should ask themselves.

4.1.1 Strategy to establish public information trust

Public information trust strategies will vary depending on factors such as the subject domain, the audience, and the objectives of actors seeking to use the organization’s public information against them.

Many organizations already have some capability for establishing trust in their public information and countering claims made against them. Using public provenance will help establish trust for an organization’s content, but it may not be as effective or have the same return on investment as other strategies.

Organizations should decide whether to use provenance as an approach to countering the challenges they face. Those choosing to use provenance technologies will also have to consider how to implement them.

4.1.2 Introduction of provenance in content lifecycle

Organizations can have a lot of content. Some of this content is publicly available. Other content, such as drafts, may not be publicly available now but will become public in the future.

The content may be at various stages of update and editing in preparation for publication. It may be distributed across a variety of systems and may be subject to changes by many individuals.

Organizations may also have some content that they never intend to make public. Some content may pose challenges or risks to the organization itself. As a result, organizations may choose strong provenance measures only for some types of content. They may also choose to protect content at the point of publication rather than at point of creation.

4.1.3 Timeframe for content verification

The public’s requirements for information verification can vary in timeframe depending on the information context. Some information verification requirements will be aimed at short-term concerns such as elections, while others will be aimed at generational issues such as evidence concerning distant historical events.

For short-term events, the organizational risk is that it will take longer to verify the provenance information than the event timeframe requires. Timeframe issues can impact how long provenance records must be maintained, as well as how readily-accessible the records need to be.

4.1.4 Cost

Digital provenance mechanisms are relatively new and have associated implementation, operation and maintenance costs. In most cases, organizations will have to change business processes to make effective use of provenance mechanisms. In addition, provenance technologies are evolving rapidly, and near-term implementations may quickly become obsolete.

Organizations may choose to prioritise non-provenance public information trust responses or they may choose to implement interim or partial solutions, for example using public provenance measures only for critical content.

4.1.5 Audience and format

The audience for provenance information may not necessarily be the same as an organization's core audience. This will depend on an organization's strategic and tactical response to the use of their information.

Formats for provenance information will be different depending on the system used by the specific audience.

Media companies have copyright on their information and may be able to use copyright tools to remove infringing material from the Internet. In this case, the audience for provenance evidence are legal professionals, Internet service providers and social media companies. Provenance information would need to be formatted to meet their different evidence requirements. A media company's implementation of provenance mechanisms will likely differ from that used by organizations whose provenance information audience is the general public.

4.1.6 Maturity of public provenance technologies

Organizations should also consider the maturity of public provenance technologies. Technologies for versioning and logging to meet an organization’s internal provenance requirements are mature. Public provenance technologies are less developed, although some of the related technologies used in private provenance, such as cryptographic hashing, can be used in public systems.

Publicly accessible provenance systems have additional requirements, for example, end-point devices such as cameras that can cryptographically sign content, and tamper-proof ledgers. These technologies are developing, but immature.

Organizations may choose to do partial and trial implementations. They may also choose to establish architectures that allow newer technologies to be integrated as they become available.

4.2 Example use cases

As we have seen, requirements for public provenance will vary between organizations depending on the challenges they face in communicating facts to their audiences and their public information trust strategy and tactics. These different requirements will shape the provenance infrastructure.

Here we provide analysis of 5 different use cases, using the provenance characteristics identified in Section 3.1 What to consider when selecting provenance systems.

4.2.1 Use case 1: Organization wants provenance of all its public content

An organization that wishes to establish provenance of its own public content can either:

- establish an irrefutable provenance record, including date and time at time of publishing

- create content provenance records for all the intermediate steps of creating the content

The provenance record then becomes a tool for the organization’s communications staff, as well as for others who review and provide fact-checking on the content, to validate or refute content veracity claims.

The public needs to be able to find and verify content easily. To be useful, the verification mechanisms must be simple, intuitive and reliable.

4.2.2 Use case 2: Organization’s content provenance is only needed for a short time

The required duration of a provenance record can vary depending on its expected use. Like many forms of digital record, some provenance records may only be required for a relatively short period, for example content that is transitory and only has short-term significance, such as event announcements. Provenance on the announcement may have value prior to the event, but the value of any provenance record will rapidly diminish afterwards.

Provenance infrastructure that supports short-duration requirements would not need to factor in long-duration requirements, which simplifies implementation and lifecycle considerations.

4.2.3 Use case 3: Organization’s content provenance is needed for a long time

Some organizations will need their provenance records to endure well into the future. First-hand accounts of noteworthy events are one example. Future generations may need to verify the authenticity of today’s digital content. This is especially true in a world where generative AI is increasingly capable.

Proving the veracity of recorded testimony in timeframes of over 25 years could be challenging as certification components for identities and timestamps may not endure. The provenance mechanism must therefore address changes in technology, as well as turnover of business entities such as certificate providers and hosting services. The verification mechanism itself must also endure.

Maintaining the provenance and verification mechanisms over the long term will likely rely on distributed content stores and ledgers given that, in time, most organizations shut down, as part of normal organizational lifecycle. Such mechanisms are still in the early stages of development and can be expensive to implement and use.

4.2.4 Use case 4: Organization needs content to retain its anonymity and privacy

Some provenance requirements have privacy and anonymity considerations, for example in the field of journalism, where sources working in dangerous environments may need to remain anonymous for their protection. This can be done using trusted anonymous identities for individuals, or trusted capture devices that preserve user anonymity. Although this diminishes the strength of the provenance claim, it can still add value.

Other provenance methods such as trusted timestamps and provenance certification by higher level entities (in this case, the journalist organization) can strengthen the provenance record, helping to retain its usefulness.

4.2.5 Use case 5: Copyright and other legal redress

Public content provenance records can potentially be used by organizations in their efforts to redress copyright infringement of their content.

The provenance mechanism can be used to identify copyright permissions available to others using the content (for example, Creative Commons licence) in a way which the public can verify.

Many jurisdictions are currently developing mechanisms to address other forms of information misuse.

Organizations implementing provenance mechanisms for this purpose may need to consider both specialised audiences and legal redress requirements in their systems design.

5. Next steps

The content provenance space is rapidly evolving to meet emerging challenges but is still mainly in the development stage. If you are considering content provenance as part of your organization's trust strategy you should:

- understand how your information and information about your organization is received by your audience and other parties, and how this impacts your audience's trust in your organization

- consider how content provenance technologies might address your organization's public trust challenges

- stay abreast of changes in technology and emerging trust threats in the information environment