Alternate format: Cyber threat bulletin: Cyber threat to operational technology (PDF, 1543 KB)

About this document

Audience

This Cyber Threat Bulletin is intended for the cyber security community. Subject to standard copyright rules, TLP:WHITE information may be distributed without restriction. For more information on the Traffic Light Protocol, see https://www.first.org/tlp/.

Contact

For follow up questions or issues please contact the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security at contact@cyber.gc.ca.

Table of contents

Assessment base and methodology

The key judgements in this assessment rely on reporting from multiples sources, both classified and unclassified. The judgements are based on the knowledge and expertise in cyber security of the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (the Cyber Centre). Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems provides the Cyber Centre with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment, which also informs our assessments. The Communications Security Establishment (CSE)’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insight into adversary behavior in cyberspace. While we must always protect classified sources and methods, we provide the reader with as much justification as possible for our judgements.

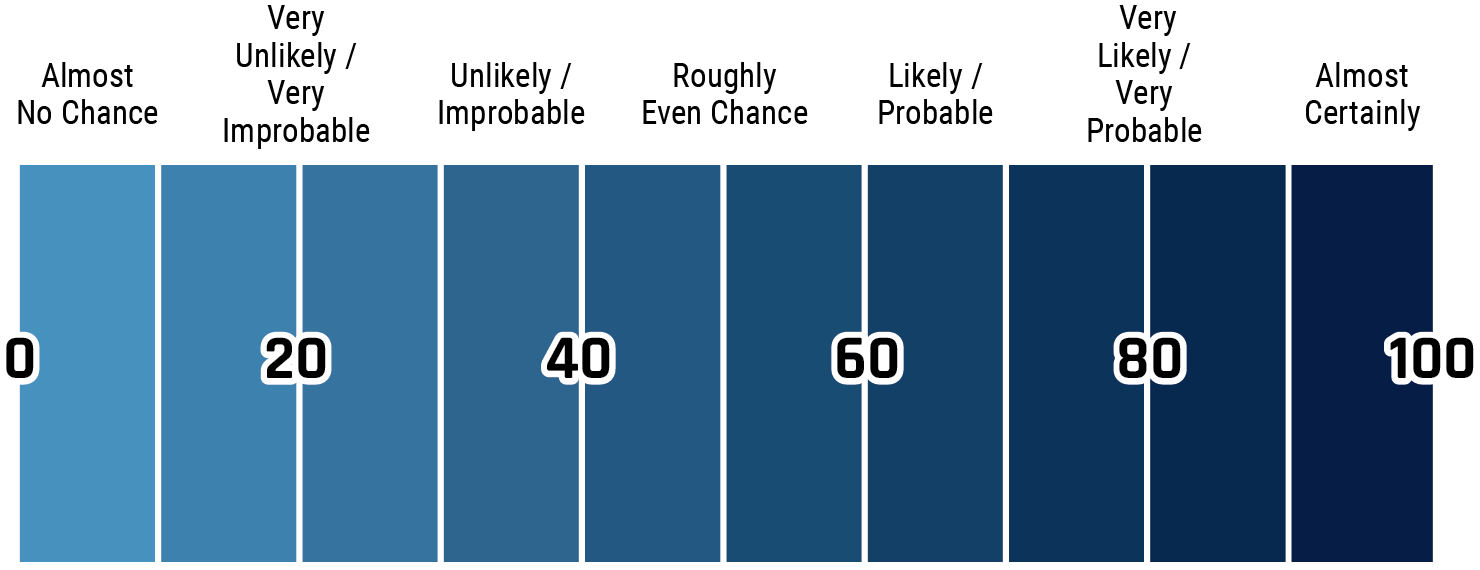

Our judgements are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases and using probabilistic language. We use terms such as “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly”, “likely”, and “very likely” to convey probability.

The contents of this document are based on information available as of 1 November 2021.

Estimative language

The chart below matches estimative language with approximate percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language

- Almost no change – 0%

- Very unlikely/very improbable – 20%

- Unlikely/improbable – 40%

- Roughly even chance – 50%

- Likely/probably – 60%

- Very likely/very probable – 80%

- Almost certainly – 100%

Key judgements

- We assess that the digital transformation of operational technology (OT)—the process of infusing OT with technology derived from the information technology (IT) domain—is almost certainly providing cyber threat actors with new opportunities to access and disrupt OT systems by exploiting the increased computing power and connectivity of OT devices. We judge that this almost certainly includes the OT systems in Canada’s critical infrastructure (CI).

- 2020 saw a spike of cyber threat activity against OT systems and OT asset owners around the world. This increase in malicious activity consisted mostly of fraud and ransomware attempts by cybercriminals against OT asset owners’ IT networks, as well as a lower level of sabotage attempts by state-sponsored actors. We expect that these trends will very likely continue in the next 12 months.

- We judge that cybercriminals are almost certainly improving their capabilities, and are very likely to attempt to target high-value Canadian organizations with large OT assets, including those in CI, in search of larger ransom payments and valuable data. Cybercriminals are also increasingly likely to directly access, map, and exploit OT for extortion with custom ransomware.

- We assess that the OT in critical infrastructure is almost certainly subject to the cyber threats experienced by any large, valuable organization, and in addition, is almost certainly a strategic target for state-sponsored cyber activity for power projection in times of geopolitical tensions.

- We assess that state cyber actors very likely have an interest in obtaining information on the OT in Canada’s critical infrastructure, and pre-positioning cyber tools within it as a contingency for potential future sabotage, in part because of integration with North America-wide systems. We judge that, in the absence of international hostilities, it is very unlikely that state-sponsored cyber threat actors will intentionally seek to disrupt Canadian critical infrastructure and cause significant damage or loss of life.

- Sophisticated cyber threat actors target the OT supply chain and service providers for two purposes: to obtain sensitive information about the OT of their actual target; and, as an indirect route to access the networks of OT targets. We assess that supply chain targeting by medium- to high-sophistication cyber threat actors will almost certainly continue in the next 12 months.

- We assess that software supply chain compromises are very likely an active, increasing threat to OT security, and that activity affecting popular software vendors highlights the potential aggregate impact of a critical vulnerability in widely-used OT products.

The cyber threat to operational technology

Introduction

Operational technology (OT) plays an essential role in the management of Canada’s critical infrastructure (CI), and as a result, the cybersecurity of OT is very important to Canada’s national security. OT—the hardware and software used to monitor and make changes in the physical world—originated primarily in industry, and commonly refers to the devices controlling industrial equipment.Footnote 1 OT is extensively used to automate industrial processes in diverse sectors like manufacturing, resource extraction, and essential services such as electricity, natural gas, and water. Due to functional gains from the digital transformation of these devices (see Table 1) OT is being used to automate many other sectors like building management, municipal services, transportation, healthcare, and others.

Table 1: OT terms: What we mean when we say…

Information Technology (IT)

Hardware and software for storing, retrieving, and communicating information; the familiar computers and communications equipment used for business and administrative tasks.

Operational Technology (OT)

Hardware and software integrated into devices used to monitor and cause changes in the physical world; widely used in heavy industry and critical infrastructure for industrial control systems.

Industrial Control Systems (ICS)

Specialized OT that monitors and controls mission-critical industrial processes. An important characteristic of ICS is its ability to sense and change the physical state of industrial equipment.

Embedded systems

A computer system that controls the operation of a physical device or machine, often highly optimized for reliability, efficiency, size, and cost.

Digital transformation of OT

Integrating OT devices with embedded systems and a network connection to allow automated decision-making, data exchange, and efficient centralized management.

The Industrial Internet of Things (IIoT)

IIoT is a form of industrial OT that allows for a higher degree of autonomy by using smart devices, Internet communications and cloud computing services.

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS)

Advanced OT, where the physical environment is deeply connected with the information world; systems that measure and control the physical world to achieve a particular goal.

The digital transformation of OT

OT came into existence before the Internet, and originally consisted of proprietary systems for industrial process control. These systems were not designed with information security in mind since they were not exposed to external threats. In the past 25 years, however, OT has adopted data processing and communications protocols from information technology (IT) to create safer, smarter, and more efficient operations. The global market for smart OT devices in 2019 was estimated to be about $205.5 billion CAD, growing at about 8% per year.Footnote 2 This digital transformation is occurring in almost all organizations with OT assets.Footnote 3 Many Canadian organizations are adopting this global trend. We judge that it is highly likely that a significant proportion of Canada’s OT is becoming accessible from the internet and other untrusted networks, and, that this will almost certainly increasingly expose these OT systems to cyber threats.

OT cybersecurity vs. IT cybersecurity

OT systems have fundamentally different operating conditions than IT systems. For example, OT devices manage equipment that may be exposed to extreme conditions such as very high temperatures and pressures, dangerous chemicals, radiation, or high voltages. The failure of an OT device could trigger the shutdown of an entire industrial process, which could be very costly. Because of this, OT design has always prioritized personal safety and process reliability (“uptime”) rather than data security, which IT networks do. Industrial assets have long lifespans, and processes tend to be stable over time, so OT devices typically have a much longer service life, often measured in decades, than IT devices. OT systems are usually managed by different groups of people than IT networks, with different backgrounds and priorities. As a result of these characteristics and conditions, OT hardware and software may be upgraded and patched less frequently, communication protocols may lack basic encryption, authentication or integrity protection features. Similarly, OT systems generally do not have security functions like intrusion detection which could delay communications, leading to a degradation of performance and safety of the system.

Historically, OT asset owners countered cyber threats by segregating or “air-gapping” OT systems from IT systems and the Internet to prevent malicious access to OT devices. However, for various reasons, such as extraction of billing and performance data, as well as device configuration and maintenance, OT systems are now nearly always permanently connected to the owner’s IT network and, increasingly, directly to the Internet.Footnote 4 We assess that the design characteristics of OT systems, and the long-term trend to network previously offline OT systems have almost certainly increased their susceptibility to cyber threat activity.

OT exposure in Canada: A snapshot

In March 2021, roughly 128,000 network ports associated with OT services responded to scans from Shodan (a search engine for Internet-connected devices) from about 62,800 unique internet protocol (IP) addresses that geolocated to Canada. About 13% of those IP addresses advertised a software version with at least one publicly-reported vulnerability from the Common Vulnerabilities and Exposures (CVE) list—a reliable, but not absolute indicator of vulnerability. We assess that this likely represents a range of Canada-based industrial OT devices that are accessible via the Internet, including equipment typically used by highly-automated CI sectors, and that a small but significant proportion of these devices are likely exploitable through known vulnerabilities (see Table 2 for the top 10). The IP addresses geolocated to every province and territory, with the highest concentrations in Ontario and Quebec. We assess that the picture of the OT attack surface from Shodan is almost certainly an under-representation of actual OT communications on public networks, since Shodan does not discover devices that use the Internet for communications, but are not directly connected. The United Kingdom (UK) and the United States (US) have issued warnings of the presence of state-sponsored cyber threat actors on Internet infrastructure such as routers, switches, and firewalls.Footnote 5 We assess that these capabilities could likely be used by cyber threat actors to collect and analyze OT communications, and to identify potentially-vulnerable devices that are not listed in widely-available databases like Shodan.

| Rank | OT network port | Approximate number of devices online | Primary use |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2222 | 39,500 | General industrial automation |

| 2 | 20000 | 24,000 | Utilities |

| 3 | 9600 | 13,500 | Manufacturing |

| 4 | 5007 | 13,000 | Manufacturing |

| 5 | 4000 | 13,000 | Oil and Gas |

| 6 | 1883 | 4,500 | IIoT, Manufacturing |

| 7 | 1911 | 3,000 | Building automation and control |

| 8 | 47808 | 3,000 | Building automation and control |

| 9 | 44818 | 2,500 | General industrial automation |

| 10 | 18245 | 2,000 | General industrial automation |

The OT of the future: Cyber-physical systems

Cyber-Physical Systems (CPS) are the intended end state of the digital transformation of OT. CPS merge advanced OT components featuring tight integration of computing, networking, and physical process management with the global information infrastructure and large-scale analytics into high-level smart-systems, such as smart factories, smart grids, and smart cities. Critical infrastructure is projected to lead in the deployment of CPS. We assess that the transition of OT to CPS will likely increase the ways that cyber threat actors might value the OT target. This could potentially come from the generation of large quantities of valuable data or follow-on access to connected clients. We assess that the transition to CPS will very likely facilitate malicious OT access, due to the expansion of the attack surface of vulnerable entry points. We assess that these changes will likely alter the cost-benefit analysis of targeting decisions by cyber threat actors. The increased value of these targets, combined with easier access, will likely lead to a large increase in the cyber threat activity against OT, including that in CI and all other sectors transitioning to CPS.

The role of OT in critical infrastructure

We assess that the digital transformation of OT to CPS will likely increasingly expose Canadian CI to cyber threats. Canada’s CI (see box “Critical Infrastructure”) includes many large industrial assets, such as electricity generation stations and the grid, water treatment facilities, oil and gas pipelines, and factories. OT is central to the management and control of these industrial processes and assets. Canadian CI has been characterized as massive, geographically dispersed, and highly-interconnected.Footnote 6 To increase the reliability and economy of critical services, the owners and providers have embraced digital transformation of the OT assets in critical infrastructure.

Cyber sabotage of OT systems in Canadian CI poses a costly threat to owner-operators of large OT assets, and could conceivably jeopardize national security, public and environmental safety, and the economy. In early May 2021, for example, Colonial Pipeline, operator of one of the largest refined products pipelines in the US, suffered an incident attributed to DarkSide, a Russia-based ransomware group. Although the activity was reported to be restricted to the IT systems, the company chose to shut down its operations, which resulted in record price increases, panic-buying and gasoline shortages.Footnote 7 A ransomware incident in late May 2021 forced the meat processing company, JBS, to halt production in multiple facilities in three countries, including a meat processing plant in Brooks, Alberta, threatening food security at a time of high demand.Footnote 8

Critical infrastructure: the processes, systems, facilities, technologies, networks, assets, and services essential to the health, safety, security or economic well-being of Canadians and the effective functioning of government.Footnote 9

The cyber threat to OT

Direct vs indirect targeting

Cyber threat actors have a choice of several routes through which to direct cyber threat activity against OT. Cyber threat activity, by definition, is digital information intended to harm the security of an information system.Footnote 10 There are two common methods of moving digital information between domains—online and offline.Footnote 11 Online threats move through the network, and offline threats are stored on digital media, such as a USB key, and moved manually.

We assess that a threat actor of medium to high sophistication (see Annex A for details of sophistication) will almost certainly consider different targeting options for both online and offline threat activity. This includes targeting an organization directly, by exploiting Internet-connected devices in the organization’s OT system, or moving laterally through OT network connections to an organization’s IT network. Another option is indirect targeting of an OT system, through targeting second and third parties in the OT supply chain of products and services. We judge that the complexity of supply chain targeting very likely limits medium- to low-sophistication actors to direct targeting.

Direct threats

The cyber threat to OT from direct targeting derives from two main sources: financially-motivated, medium-sophistication cybercrime groups, and politically-motivated, high-sophistication state-sponsored cyber threat actors. Other potential actors, such as terrorists, hacktivists, and thrill seekers tend to be low-sophistication and present a much lower threat.Footnote 12

From the beginning of 2010 to the end of 2020, the Cyber Centre noted 26 significant publicly-reported cyber incidents from around the world where OT was targeted or affected (Figure 1).Footnote ** We assess that these incidents are likely representative of significant OT cyber incidents, but very likely do not include numerous low-impact incidents that many organizations are exposed to, but do not report.

From 2010 to 2019, there were on average about 2 significant incidents per year, but in 2020, that number increased to 8. We assess that the 2020 spike in cyber activity that affected OT was almost certainly due to an increase in criminal actor activity against large industry, where the OT effect was a by-product of targeting IT networks, as well as OT targeting by states.

While we have observed an increase in activity, we assess that overall sophistication of cyber activity against OT has very likely not changed over time. We judge that the cyber threat activity impacting OT targets has to date consisted of a mix of fraud and ransomware attempts by cybercriminals, as well as espionage and pre-positioning of cyber tools by state-sponsored actors. Hacktivists, thrill seekers, and disgruntled individuals appear to have only caused small-scale disruptions in OT performance.

Long description

| Year | Cybercriminal | Others | State-sponsored |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2011 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 2012 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2013 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 2014 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 2015 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2016 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2017 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2018 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 2019 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 2020 | 6 | 0 | 2 |

Threats to OT from cybercriminals

We assess that cybercrime groups will almost certainly continue to target large organizations with OT assets, including organizations in Canada, in medium-sophistication attacks to try to extract ransom, steal intellectual property and proprietary business information, and obtain personal data about customers. In 2020, we assessed that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to scale up their ransomware operations and attempt to coerce larger payments from victims by threatening to leak or sell their data online.Footnote 13 We assess that cybercriminals are almost certainly increasingly targeting heavy industry and the essential services in CI in order to increase their chances of obtaining a large ransom.

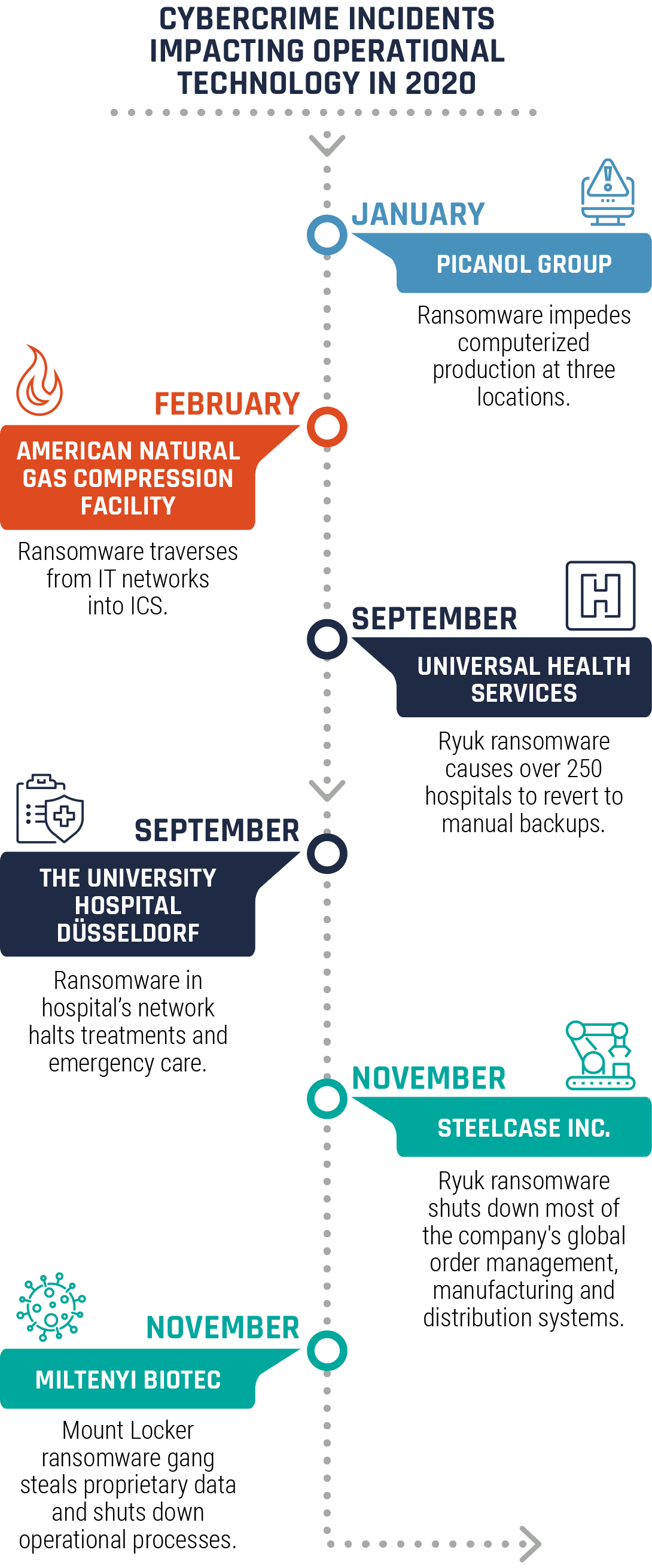

Even if the cyber activity is contained in the IT network of an OT asset owner, there is still a possibility of an OT shutdown.Footnote 14 In 2020, ransomware attacks that affected OT systems spiked (Figure 1); the incidents were severe enough to force at least six OT asset owners to shut down some or all of their industrial OT operations for safety or business reasons. The impact of a ransomware attack on an OT asset owner varies according to the specific circumstances of the industrial process and the reaction of the site staff. For example, in March 2019, a Norwegian aluminum company was impacted by a ransomware event that disrupted logistical and production data, and the company decided to shut down those OT systems with limited manual mode operations, in some cases relying on paper copies of orders.Footnote 15 During Fall 2020, a wave of ransomware hit the healthcare sector,Footnote 16 including a September incident where Ryuk ransomware locked the computers in more than 250 US hospitals, forcing staff to revert to manual processes and delaying medical procedures.Footnote 17

We have previously assessed that ransomware operators have almost certainly improved their ability to impact large corporate IT networks to the point that they can detect connected OT systems.Footnote 18 In January 2019, a ransomware variant called EKANS or SNAKE emerged, with instructions to terminate OT processes that would normally only run on OT workstations.Footnote 19 Ransomware can also migrate to OT through network misconfiguration (see “Emerging OT Vulnerability” text box). In February 2020, ransomware impacted a US natural gas compression facility, traversing Internet-facing IT networks into the OT system responsible for monitoring pipeline operations, prompting a shutdown.Footnote 20 We assess that cybercriminals are aware of OT systems, and are almost certainly improving their capabilities to eventually attempt to access, map, and exploit the OT of their targets for extortion with customized ransomware.

Long description

| Date | Lead | Description |

|---|---|---|

| January | Picanol Group | Ransomware impedes computerized production at three locations. |

| February | American Natural Gas Compression Facility | Ransomware traverses from IT networks into ICS. |

| September | Universal Health Services | Ryuk ransomware causes over 250 hospitals to revert to manual backups. |

| September | The University Hospital Düsseldorf | Ransomware in hospital’s network halts treatments and emergency care. |

| November | Steelcase Inc. | Ryuk ransomware shuts down most of the company's global order management, manufacturing and distribution systems. |

| November | Miltenyi Biotec | Mount Locker ransomware gang steals proprietary data and shuts down operational processes. |

Emerging OT vulnerability: Identity and Access Management (IAM) spanning IT and OT

IAM synchronization between IT and OT networks (for ease of administration) is an emerging OT vulnerability. Cyber actors are learning to exploit IAM servers to facilitate lateral movement in a network. Synchronizing or mirroring the IAM service into an otherwise protected OT network gives these actors access to vulnerable OT assets. An incident using this method was reportedly the cause of a US pipeline shutdown from ransomware in 2019.Footnote 21

Long description

| Date | Lead | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2010 | Iranian Nuclear Facilities | Stuxnet first to target OT in Iranian nuclear enrichment facilities. |

| 2012 | Saudi Aramco and RasGas | State-sponsored Iranian actors deploy Shamoon wiper malware to IT networks; OT unaffected. |

| 2013 | Bowman Dam | State-sponsored Iranian actors infiltrate the control system and gain access to flood gates. |

| 2014 | Havex Campaign | Russian-sponsored APT launches a global cyber- espionage operation against companies with OT assets. |

| 2014 | German Steel Mill | Unattributed state actors disrupt the control system, preventing a blast furnace from shutting down. |

| 2015 | Kyiv's Electricity Grid (1 of 2) | Russian Blackenergy malware used in unprecedented attack on CI: a portion of the city's grid loses power. |

| 2016 | Kyiv's Electricity Grid (2 of 2) | Russian state actors use CrashOverride malware to disrupt power supply. |

| 2017 | UK Energy Companies | State-sponsored actors penetrate the ICS of multiple UK energy companies. |

| 2017 | Istanbul Electricity Grid | Energy Minster claims a severe state-sponsored cyberattack targeted the city's power grid. |

| 2017 | Oil and Gas Facility | Russian-sponsored Triton OT malware triggers plant shutdown. |

| 2018 | Western CI Supply Chain | Russian-sponsored Dragonfly 2.0 infiltrates the supply chain of CI OT asset owners. |

| 2020 | Israel and Iran Trade CI Attacks | Iranian-sponsored APT targets two Israeli water pump stations. Israel disrupts operations at an Iranian port. |

Threats from State-sponsored Actors

We assess that OT is almost certainly targeted by states for a variety of possible reasons: espionage, theft of commercial intellectual property (IP), messaging of intent, and prepositioning for sabotage. The Cyber Centre is aware of low frequency state-sponsored cyber threat activity targeting Canadian OT-related organizations in critical infrastructure since at least 2012.

We assess that large OT asset owner-operators, especially the utilities in critical infrastructure, are not likely targets for the theft of commercial IP, because the commercially-valuable IP primarily resides in the supply chain. We judge that the purpose of cyber activity against CI OT asset owners was likely to collect information and pre-position cyber tools as a contingency for possible follow-on activities, or as a form of influence, from a demonstration of state cyber power. These early stages of a potential future cyber attack tend to resemble industrial espionage.Footnote 22 We assess that it is very likely that state actors are using the information gathered from their espionage activities to develop additional cyber capabilities that would allow them to sabotage OT used in Canada’s critical infrastructure sectors.

In the past decade, state-sponsored cyber activity against OT, especially the OT in critical infrastructure, has become a regular feature of global cyber threat activity. In 2013, one of the first reported events was an infiltration of the US Bowman Avenue Dam control systems, attributed to Iran.Footnote 23 Two years later, in 2015, an undisclosed state-sponsored actor launched a sophisticated social engineering campaign against an unnamed German steel mill. The operation disrupted the facility’s controls systems, preventing a blast furnace from shutting down properly, and caused physical destruction.Footnote 24

The first state-sponsored cyber activity to sabotage critical services occurred in 2015 and 2016 against the electricity grid in Ukraine. In late 2015, Russian cyber actors were able to de-energize seven substations from three Ukrainian regional distribution companies for three hours, causing a power outage that affected 225,000 customers. A year later, a cyber incident at Ukraine's national power company, Ukrenergo, caused a one-hour outage in northern Kyiv.Footnote 25 These incidents, conducted in the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, were a turning point in the history of cyber activity against the electricity sector, demonstrating the impact of a cyber attack against critical infrastructure, and its use during international hostilities.

Escalating tensions between Iran and Israel led to state-sponsored operations against each other’s critical infrastructure in 2020. Iranian-sponsored actors likely launched unsuccessful cyber campaigns at Israel’s water infrastructure, targeting command and control and other OT systems of two Israeli water facilities. Had these activities succeeded, the operation would have triggered pump shutdowns and left thousands without water.Footnote 26 In response, Israel allegedly compromised a prominent Iranian port terminal, disrupting operations and knocking computers offline for several days.Footnote 27

We assess that the OT in critical infrastructure is almost certainly a strategic target for state-sponsored cyber activity, especially for power projection in times of geopolitical tensions. We judge that it is very unlikely that state-sponsored cyber threat actors will intentionally seek to sabotage Canadian critical infrastructure and cause destruction or loss of life in the absence of international hostilities. For economic and reliability reasons, Canada’s CI is integrated with that of the US, and we assess that this also likely increases the chance that a service disruption from a cyber attack against the US would be jointly felt by both Canadians and Americans. US assessments characterize the cyber threat to their critical infrastructure from state-sponsored actors as complex and aggressiveFootnote 28 and have declared that the threats to their critical infrastructure OT by foreign adversaries and sophisticated cyber criminals constitute a national emergency.Footnote 29

State-sponsored cyber capability development

In 2017, Russian cyber threat actors tested a capability called Triton (a.k.a. Trisis) to modify the performance of a Safety Instrumented System (SIS) at a Middle Eastern oil and gas facility. An SIS is a specialized OT device designed to independently detect out-of-range conditions in an industrial process and if needed, initiate a safe shutdown of the equipment. The actors gained remote access for the facility and reprogrammed the SIS controllers, inadvertently causing them to enter a failed state, resulting in an automatic shutdown of the industrial process and subsequent investigation.Footnote 30 Malicious modification of an SIS by itself can trigger a disruptive shutdown, but in combination with tampering with other OT, could have destructive consequences.Footnote 31 Triton was designed to prevent safety systems from functioning correctly, and although it was specific to the software and equipment versions at the facility,Footnote 32 we assess that these actors would likely be able to modify their capability to target similar systems, and that actors of similar sophistication would likely be able to use these methods to develop a similar capability.

Other Actors

We assess that cyber threat actors who presently lack access to sophisticated cyber capabilities, such as terrorists, hacktivists, and thrill seekers are more likely to engage in disruptive, nuisance-level OT activity, such as the 2014 Daktronics Vanguard roadside signs incident, where individuals gained unauthorized access to digital highway signs and posted false warnings.Footnote 33 Pre-built cyber tools and training in their use are becoming readily available via the Internet (see box “Advanced Cyber Tools”), and we judge that there is an even chance that low sophistication actors with the intent to disrupt OT could adopt these tools to mount a successful sabotage attack.

Advanced cyber tools and skills are becoming accessible to more threat Actors

We assess that the wide availability of free, stolen, commercial and criminal cyber capabilities and services is likely lowering the threshold of sophistication necessary to target and sabotage OT. In the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020,Footnote 34 we assessed that the development of commercial markets for cyber tools and talent has reduced the time it takes for states to build cyber capabilities and increased the number of states with cyber programs. Some of these vendors are developing OT-specific capabilities for sale to clients. As more states have access to commercial cyber tools, states that are interested in sabotaging OT, but previously lacked the capability, can now more readily undertake this type of cyber activity. The proliferation of commercial tools to state cyber programs also makes it more difficult to identify, attribute, and defend against this cyber threat activity.

There are OT-specific exploit modules in free cyber tools as well, such as the open source Metasploit framework developed and released by researchers and security professionals for testing OT network defences. These tools are widely available to actors of all sophistication levels and include documentation and tutorials in their use.Footnote 35 The Cyber Centre is aware of high-impact crimeware such as Trickbot, Qakbot, Dridex, etc., using the leaked commercial cyber tool Cobalt Strike to target large organizations and critical infrastructure in Canada. Both Metasploit and Cobalt Strike are in wide use by states and criminal groups to facilitate cyber espionage and ransomware activity.Footnote 36 In addition, a large illegal market for cyber tools and services is greatly reducing the start-up time for cybercriminals and enabling them to conduct more complex and sophisticated campaigns. Many online marketplaces allow vendors to sell specialized cyber tools and services that users can purchase and use to commit cybercrimes, including espionage, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, and ransomware attacks, any of which could be used by actors intending to sabotage OT systems.

Indirect cyber threats to OT from the supply chain

We assess that medium- to high-sophistication cyber threat actors are increasingly likely to consider targeting OT indirectly, by first targeting the OT supply chain. Cyber threat actors target the OT supply chain for two general purposes: to obtain commercially-valuable intellectual property and information about the OT in use; and, as an indirect route to access an OT network. Large industrial asset operators, including those operating CI, depend on a diverse supply chain of products and services from laboratories, manufacturers, vendors, integrators, and contractors, as well as Internet, cloud, and managed service providers for daily operation, maintenance, modernization, and development of new capacity. OT asset owners’ dependency on the supply chain is a critical vulnerability that gives cyber actors inside information on, and opportunities for access to otherwise protected OT systems. We assess that medium- and high-sophistication actors will almost certainly continue to target the OT supply chain for these purposes for the next 12 months and beyond.

Obtaining sensitive information about OT

We assess that high-sophistication cyber threat actors almost certainly target the OT supply chain to obtain sensitive information about clients’ OT assets that they can use to develop cyber sabotage capabilities. For example, in 2014, and again in 2017, Russia-associated cyber threat actors undertook an espionage campaign against a variety of supply chain targets that were later linked to exploitation of energy sector targets.Footnote 37 In 2019, reports linked Iran to cyberespionage activity against manufacturers, suppliers, and operators of ICS equipment.Footnote 38

Accessing OT systems indirectly

A supply chain compromise occurs when products are deliberately exploited and altered prior to use by a final consumer.Footnote 39 While a supply chain compromise could occur in hardware or software, threat actors have often focused on malicious additions or injections to legitimate software in distribution or update channels (see box on dependency confusion/substitution attacks). Frequently, threat actors tamper with the end product of a given vendor so that it carries a valid digital signature, and unwitting end-users obtain the signed product through trusted download or update sites.Footnote 40 In 2014, Russian state-sponsored cyber actors compromised the networks of three OT vendors and replaced legitimate software updates with corrupted packages that included Havex malware. Users of the OT products downloaded what they believed were updates, and unknowingly installed Havex in their OT systems, giving the cyber threat actors access to various organizations related to the European energy sector.Footnote 41

Emerging supply chain cyber threat: Substitution attacks on public source code.

Most software is an assembly of components from both private and public sources.Footnote 42 Public sources provide developers with a wide range of high-quality, free code, but many large public code sharing systems allow authors to share their software “packages” without proof of identity. The availability of quality, free software makes development more efficient, but dependencies on public sources are a potential source of malware.

One method of exploiting the development process is called the “substitution attack” (or “dependency confusion”) where public sources are manipulated to fetch similarly named but malicious versions of packages.Footnote 43 An ethical hacker recently fooled e-commerce company Shopify into installing a benign package called “shopify-cloud” into their software, and after notifying the company of the breach, received a bug bounty.Footnote 44 Substitution attacks could allow a malicious cyber actor to put malware into numerous OT devices, covertly, without access to either the manufacturer or the target OT system.

In December 2020, FireEye discovered a global intrusion campaign, almost certainly the work of the Russian Intelligence Services (SVR),Footnote 45 who created malicious updates of the widely-used SolarWinds Orion network monitoring and management software by exploiting access to the company’s build process.Footnote 46 The updates were deployed to more than 16,000 SolarWinds clients,Footnote 47 and the actors were able to compromise a smaller subset of target networks with additional malware for cyber espionage, including, potentially, critical infrastructure organizations and other private sector OT asset owners,Footnote 48 as well as members of the OT supply chain.Footnote 49 We assess that software supply chain compromises are very likely an active, increasing threat to OT security, and that activity affecting large-scale software vendors highlights the potential aggregate impact of a critical vulnerability in widely-used OT products. We judge that supply chain compromises are very likely to be in software rather than hardware, but a malicious hardware alteration is not out of the range of abilities of the most sophisticated state-sponsored cyber threat actors (see box US supply chain security order).

US supply chain security order

Executive Order (EO) 13920 of 1 May 2020 authorizes the US government to work with the electricity sector to secure the US bulk power system (BPS) supply chain by eliminating high-risk foreign components. This EO prohibits the acquisition, transfer, or installation of BPS equipment with “foreign interests.” This EO also requires that such equipment in use by US asset owners be identified, isolated, and replaced.Footnote 50

In addition to targeting the supply chain, it is very likely that foreign state-sponsored actors and cybercriminals are attempting to leverage service providers’ privileged access to their clients’ systems as an indirect route into their true targets, including OT systems. For example, since at least 2019, ransomware operators have compromised MSPs and used remote management software to automatically install ransomware on multiple client networks at once. In August 2019, the cybercriminals responsible for REvil ransomware compromised a US MSP to infect 22 US municipalities and demanded cryptocurrency valued at $3 million CAD at the time. On 4 April 2017, the Cyber Centre warned of ongoing malicious cyber activity targeting MSPs internationally,Footnote 51 and in 2018, Canada and its Allies attributed the activity to a Chinese state-sponsored actor.Footnote 52 We assess that as OT systems evolve to CPS, OT systems will become increasingly integrated into service provider systems, and so subject to provider security measures, which may not consider OT-specific threats in their assessments.

Conclusion

The cyber threat landscape experienced by the OT asset operators in Canada is evolving, and cyber threat actors continue to adapt their activities to try to stay ahead of defenders. In this assessment, we show that cyber threats to OT are also threats to Canada’s essential services and critical infrastructure. We identify trends within the OT threat landscape, including the growing threat from cybercriminals, the threat from state-sponsored actors, as well as the introduction of new threat vectors stemming from the adoption of new technology and Internet-connected devices.

As noted in the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020, many cyber threats can be mitigated through awareness and best practices in cyber security and business continuity. Cyber threats continue to succeed today because they exploit deeply-rooted human behaviours and social patterns, and not merely technological vulnerabilities. Defending Canada against cyber threats and related influence operations requires addressing both the technical and social elements of cyber threat activity. Cyber security investments will allow Canadians to benefit from new technologies while ensuring that we do not unduly risk our safety, privacy, economic prosperity, and national security.

The Cyber Centre is dedicated to advancing cyber security and increasing the confidence of Canadians in the systems they rely on daily, offering support to CI and other systems of importance to Canada. We approach security through collaboration, combining expertise from government, industry, and academia. Working together, we can increase Canada’s resilience against cyber threats. Cyber security investments will allow OT asset operators to benefit from new technologies, while avoiding undue risks to the safe and reliable provision of critical services to Canadians.

Useful resources

- An introduction to the Cyber Threat Environment

- National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020

- Cyber Threat Bulletin: The Cyber Threat to Canada's Electricity Sector

- Cyber Threat Bulletin: Modern Ransomware and Its Evolution

- Baseline Cyber Security Controls for Small and Medium Organizations

- Top 10 IT Security Actions for Internet Connected Systems

- Cyber Centre’s Advice on Mobile Security

- Ransomware: How to Prevent and Recover

- Protect Your Organization from Malware

- IoT Security for Small and Medium Organizations

- Security Review Program Fact Sheet

- Cyber Security Considerations for Contracting with Managed Service Providers

- Malicious Cyber Activity Targeting Managed Service Providers

- Application Allow Lists Explained

- Security Vulnerabilities and Patches Explained

- Joint Report on Publicly Available Hacking Tools

- Cyber Security Tips for Remote Work

- Security Tips for Organizations with Remote Workers

- Focused Guidance Surrounding COVID-19, List of Publications per Audience

- COVID-19 and Malicious Websites

- Canadian Shield – Sharing the Cyber Centre’s Threat Intelligence to Protect Canadians During the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Have You Been Hacked?

- Protecting Your Organization from Denial of Service Attacks

- Spotting Malicious Email Messages

- Implementing Multi-Factor Authentication

- How Updates Secure Your Device

- Steps to Address Data Spillage in the Cloud

- Protecting High-Value Information

- Supply Chain Security for Small and Medium-sized Organizations

- Technology Supply Chain Guidelines

- Using Your Mobile Device Securely

- Security Considerations for Mobile Device Deployments

- Best Practices for Passphrases and Passwords

- Don't Take the Bait: Recognize and Avoid Phishing Attacks

- Little Black Book of Scams

- Keyloggers and Spyware

- Doppelganger Campaigns and Wire Transfer Fraud

| Level of sophistication | Sophistication characteristics | Typical cyber threat Actors |

|---|---|---|

| Low |

|

States, hacktivists, cybercriminals, thrill-seekers |

| Medium |

|

States, cybercriminals |

| High |

|

States, cybercriminals |

Annex B: Data collection and analysis

To quantify the cyber threat to OT, the Cyber Centre collected data on global cyber incidents from available open-source cyber incident databases, international media outlets, and vendor reporting, and collated a list of significant cyber incidents that occurred between 2010 to 2020. Details for each incident were examined, including date, victims, and sectors impacted. Threat actor type and motive, and sophistication of the incident were also assessed. If the victim organization owned an OT system, the Cyber Centre attempted to determine whether the OT asset was impacted (directly or indirectly) by the cyber activity. This includes OT shutdowns indirectly resulting from cyber activity in administrative IT networks.

Annex C: OT-Related cyber security incidents

| Year | Target | Description | Alleged origins | Sophistication assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2010 |

|

Stuxnet first to target OT in Iranian nuclear enrichment facilities. The malware disrupted the industrial computers at Iran’s uranium enrichment plants, dropping productivity by 30% over the course of a year. TTPs: Stuxnet malware, Zero-day exploits.Footnote 53 |

State-Sponsored | high |

| 2012 |

|

State-sponsored Iranian actors deploy Shamoon wiper malware to IT networks, deleting data on 30,000 computers and infecting (without causing damage) OT control systems. TTPs: Shamoon Malware.Footnote 54 |

Iran | medium |

| 2013 |

|

Iranian cyber threat actors gain access to the Bowman dam’s flood gate control system, but were not able to have any effect because the flood gates were offline for maintenance. TTPs: Undisclosed Malware, Spear-phishing.Footnote 55 |

Iran | low |

| 2014 |

|

Russian state-sponsored threat actor Dragonfly launches a global cyber-espionage operation against US and European companies with OT assets. TTPs: Havex Remote Access Trojan (RAT), Watering Hole Attacks.Footnote 56 |

Russia | high |

| 2015 |

|

Cyber threat actors infiltrated a German steel mill via a social engineering campaign, and caused physical destruction by disrupting controls systems that prevented the blast furnace from shutting down properly. TTPs: Spear-Phishing, Social Engineering.Footnote 57 |

Likely State-Sponsored | high |

| 2015 |

|

Russian Blackenergy malware used in unprecedented attack on Ukrainian critical infrastructure. Coordinated incidents targeted and damaged several regional distribution power companies’ SCADA systems, resulting in a 3–6-hour outage affecting approximately 225,000 Ukrainians. TTPs: Blackenergy Malware, Spear-Phishing, DoS.Footnote 58 |

Sandworm (Russia) |

high |

| 2016 |

|

Russian malware used to shut down remote terminal units from the Pivnichna power transmission facility, resulting in a partial blackout and a 20 percent power consumption loss in Kyiv. TTPs: Industroyer/ Crashoverride Malware.Footnote 59 |

Sandworm (Russia) |

high |

| 2017 |

|

The Turkish Energy Minister stated a severe cyber incident targeted electricity transmission and producing lines, causing widespread electricity cuts across Istanbul. TTPs: Undisclosed.Footnote 60 |

Unattributed | high |

| 2017 |

|

UK GCHQ issued an alert indicating hackers penetrated industrial control systems of UK energy companies. TTPs: Undisclosed Malware, Spear-Phishing.Footnote 61 |

State-Sponsored | high |

| 2017 |

|

Cyber threat actors gained remote access to a SIS engineering workstation, and reprogrammed an SIS unit with Triton malware; errors prompted an automatic shutdown of the industrial process. TTPs: Triton/Trisis Malware.Footnote 62 |

Xenotime (Russia) |

high |

| 2018 |

|

A supply chain incident where threat actors breached third-party entities and moved laterally to high-value asset owners within the energy sector; they stole confidential data on ICS and other processes. TTPs: Spear-Phishing Waterhole Domains, Host-Based Exploitation.Footnote 63 |

Energetic Bear / DragonFly (Russia) |

high |

| 2020 |

|

Israel successfully defended against two cyber incident’s targeting the command and control systems of water treatment plants, pumping stations, and sewage in the country. TTPs: Undisclosed.Footnote 64 |

Jerusalem Electronic Army (Iran) |

medium |

| 2020 |

|

Hackers disrupted operations the port, knocking computers offline for several days; impeding traffic. TTPs: Undisclosed.Footnote 65 |

Israel | high |

| Year | Target | Description | Alleged origins | Sophistication assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 |

|

A virus infected all of the power plant's machines using the Alstrom ALSPA system, disrupting operations and management systems. TTPs: Conficker virus.Footnote 66 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2012 |

|

An employee unknowingly inserted an infected USB into the network, keeping the plant offline for three weeks. TTPs: Mariposa Malware.Footnote 67 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2014 |

|

Hackers took advantage of weak password security and broke into the system; however, scheduled maintenance disconnected the mechanical devices from the control system. TTPs: Brute Force.Footnote 68 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2016 |

|

Hackers stole confidential financial records and accessed the water district's valve and flow control application responsible for manipulating hundreds of PLCs that control water treatment chemical processing. TTPs: SQL Injection, Spear-Phishing.Footnote 69 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2018 |

|

Ransomware shut down 2,000 computers for several days, costing the department an estimated 1.7 million (USD). TTPs: SamSam Ransomware.Footnote 70 |

Unattributed | medium |

| 2019 |

|

The incident disrupted operations (logistical and production), forcing some of the company's aluminum plants to switch to manual processes. The financial impact is approximately $71 million. TTPs: LockerGoga Ransomware.Footnote 71 |

Unattributed | medium |

| 2019 |

|

The ransomware shut down IT systems, affecting more than 250,000 people through regional blackouts, and prevented customers from purchasing prepaid electricity. TTPs: Undisclosed Ransomware.Footnote 72 |

Unattributed | medium |

| 2020 |

|

At three satellite locations, the incident halted computerized production as the company did not have access to its systems—an estimated 196 plant days lost. TTPs: Undisclosed Ransomware. Footnote 73 |

Unattributed | medium |

| 2020 |

|

The facility shut down operations for two days once the ransomware traversed from IT networks into ICS responsible for monitoring pipeline operations, impacting assets on the OT system like human-machine interfaces (HMIs), data historians, and polling servers. TTPs: Undisclosed Ransomware, Spear-Phishing.Footnote 74 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2020 |

|

The incident caused over 250 hospitals to revert to manual backups, divert ambulances, and reschedule surgeries; it may have contributed to four deaths. TTPs: likely Ryuk Ransomware, Phishing, Emotet Trojan.Footnote 75 |

likely WIZARD SPIDER | medium |

| 2020 |

|

Through an unpatched vulnerability, hackers penetrated the hospital’s network with ransomware, forcing planned and outpatient treatments and emergency care to have to occur elsewhere. TTPs: Undisclosed Ransomware, Code Exploit.Footnote 76 |

Unattributed | low |

| 2020 |

|

The incident caused an operational shutdown of most of the company's global order management, manufacturing and distribution systems, significantly delaying shipments. Plant-days lost is an estimated 140 days. TTPs: Ryuk Ransomware.Footnote 77 |

likely WIZARD SPIDER | medium |

| 2020 |

|

The organization shut down operational processes for two weeks worldwide; hackers stole approximately 150 GB of company data. TTPs: Mount Locker Ransomware.Footnote 78 |

Mount Locker ransomware gang | low |

| Year | Target | Description | Alleged origins | Sophistication assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 |

|

Hackers accessed a backdoor into the ICS system that allowed access to the key control mechanism for the company's internal heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC) units. TTPs: Undisclosed Malware, Code Exploits.Footnote 79 |

Thrill-Seeker | low |

| 2014 |

|

Threat actors hacked into roadside signs and posted bogus warnings. TTPs: Code exploits.Footnote 80 |

Thrill-Seeker | low |