Alternate format: 2019 update: Cyber threats to Canada's democratic process (PDF, 6.81 MB)

About us

The Communications Security Establishment (CSE) is Canada’s centre of excellence for cyber operations. As one of Canada’s key security and intelligence organizations, CSE protects the computer networks and information of greatest importance to Canada and collects foreign signals intelligence. CSE also provides assistance to federal law enforcement and security organizations in their legally authorized activities, when they may need CSE’s unique technical capabilities.

CSE protects computer networks and electronic information of importance to the Government of Canada, helping to thwart state-sponsored or criminal cyber threat activity on our systems. In addition, CSE’s foreign signals intelligence work supports government decision-making in the fields of national security and foreign policy, providing a better understanding of global events and crises and helping to further Canada’s national interest in the world.

Launched on 1 October 2018 as part of CSE, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is a new organization, but one with a rich history. The Cyber Centre brings operational security experts from across the Government of Canada under one roof. In line with the National Cyber Security Strategy, the launch of the Cyber Centre represents a shift to a more unified approach to cyber security in Canada.

CSE and the Cyber Centre play an integral role in helping to protect Canada and Canadians against foreign-based terrorism, foreign espionage, cyber threat activity, kidnapping of Canadians abroad, attacks on our embassies, and other serious threats with a significant foreign element, helping to ensure our nation’s security, stability, and prosperity.

Table of contents

Executive summary

Here’s what you need to know in 2019:

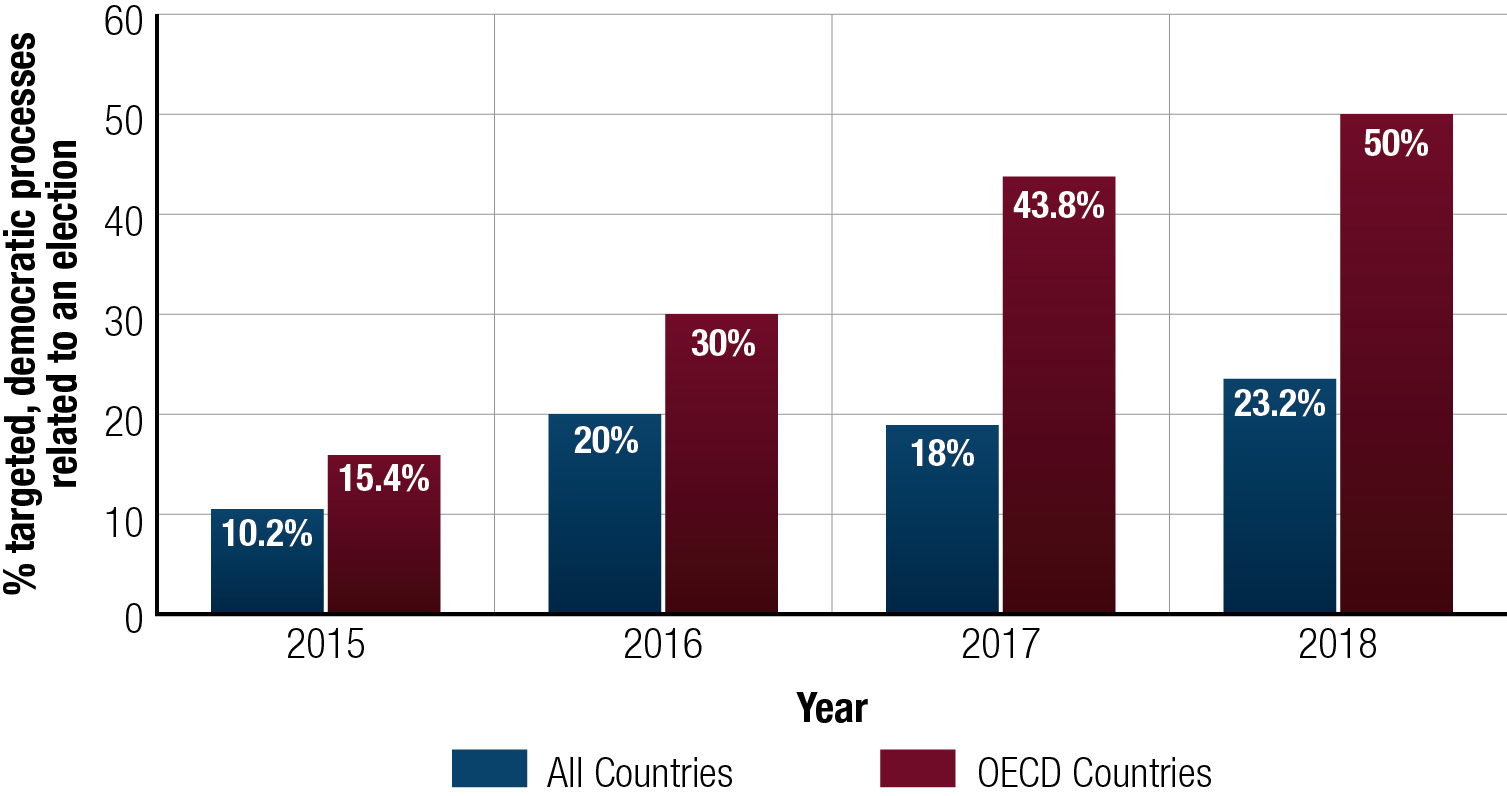

- In 2018, half of all advanced democracies holding national elections had their democratic process targeted by cyber threat activity. This represents about a three-fold increase since 2015 and we expect the upward trend to continue in 2019.

- Foreign cyber interference – interference activity enabled by cyber tools – targeting voters has become the most common type of cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide. Cyber threat actors manipulate online information, often using cyber tools, in order to influence voters’ opinions and behaviours.

- We judge it very likely that Canadian voters will encounter some form of foreign cyber interference related to the 2019 federal election. However, at this time, it is improbable that this foreign cyber interference will be of the scale of Russian activity against the 2016 United States presidential election.

- We judge it very likely that foreign cyber interference against Canada would resemble activity undertaken against other advanced democracies in recent years. Foreign adversaries have attempted to sway the ideas and decisions of voters by focusing on polarizing social and political issues, promoting the popularity of one party over another, or trying to shape the public statements and policy choices of a candidate.

- Since our 2017 report, political parties, candidates, and their staff have continued to be targeted worldwide by cyber threat activity - though to a lesser extent than voters. Cyber threat actors use cyber tools to target the websites, e-mail, social media accounts, and the networks and devices of political parties, candidates, and their staff.

- Elections around the world have also continued to be targeted by cyber threat activity over the past years. However, as we noted in 2017, Canada’s federal elections are largely paper-based and Elections Canada has a number of legal, procedural, and information technology (IT) measures in place that provide very robust protections against attempts to covertly change the official vote count.

About this document

This document provides an update to the 2017 report released by CSE. Its purpose is to let Canadians know about the cyber threats to our democratic process in 2019.

Scope

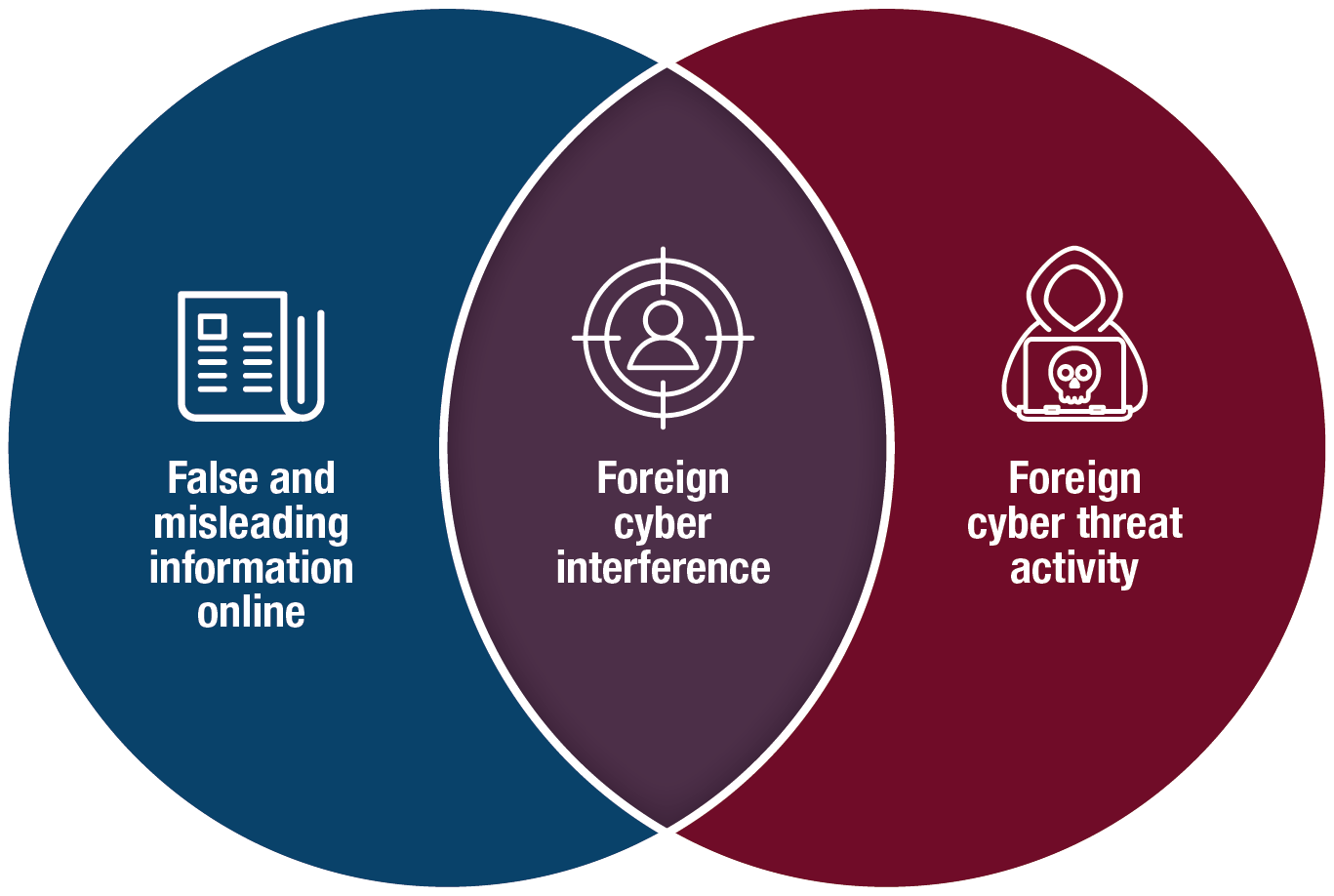

This report considers cyber threat activity – including foreign cyber interference – that affects the democratic process. Cyber threat activity involves the use of cyber tools (e.g. malware and spearphishing) to compromise the security of an information system by altering the confidentiality, integrity and availability of a system or the information it contains. Foreign cyber interference occurs when threat actors use cyber tools to covertly manipulate online information, in particular via social media, in order to influence voters’ opinions and behaviours.

Long description

This report addresses Foreign Cyber Interference, which is the intersection of False and Misleading Information Online and Cyber Threat Activity.

Sources

In producing this document, we relied on reporting from both classified and unclassified sources. CSE’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insights into adversary behaviour. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems also provides CSE with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment.

Limitations

We discuss a wide range of cyber threats to global and Canadian political and electoral activities, particularly in the context of Canada’s upcoming 2019 federal election. Providing cyber threat mitigation advice is outside the scope of this document.

More information

Further resources can be found on the Cyber Centre’s website in documents such as the Top 10 IT Security Actions and the Get Cyber Safe Campaign.

For readers interested in more detailed information about cyber tools and the evolving cyber threat landscape, we refer you to CSE’s fall 2018 publications, the National Cyber Threat Assessment and An Introduction to the Cyber Threat Environment.

Assessment process

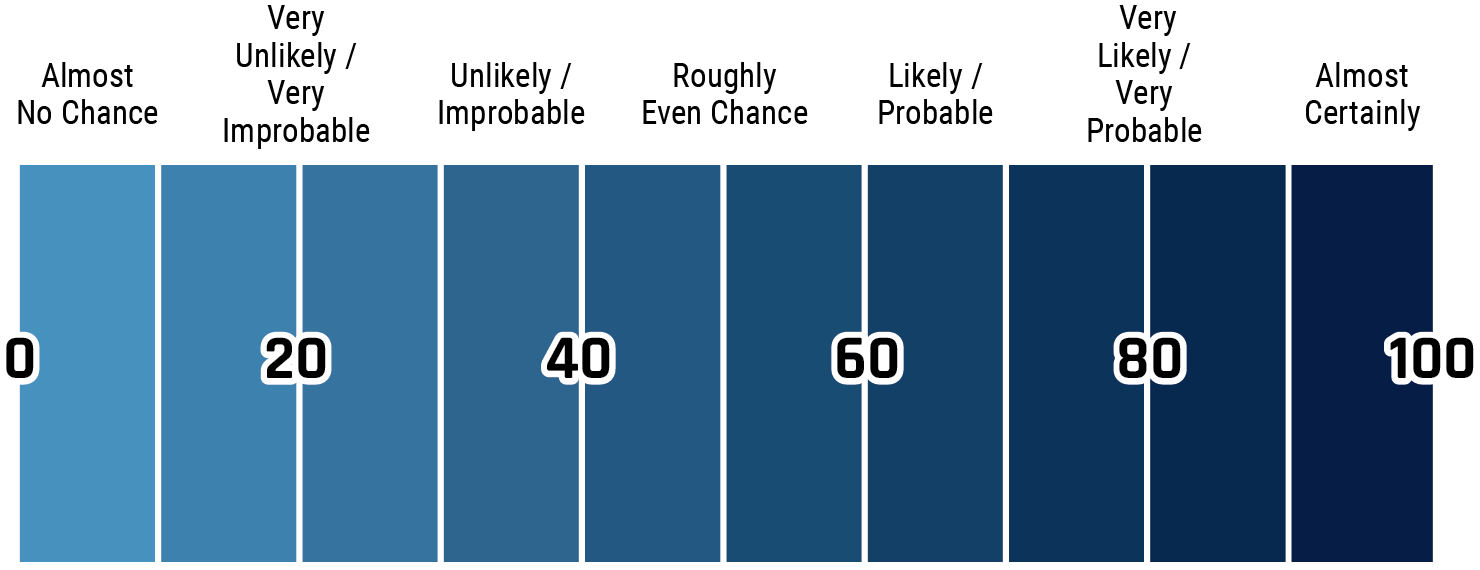

This assessment is based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases, and using probabilistic language. We use the terms “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly,” “likely,” and “very likely” to convey probability.

Estimative language

The chart below matches estimative language with approximate percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Long description - Estimative language

- Almost no change – 0%

- Very unlikely/very improbable – 20%

- Unlikely/improbable – 40%

- Roughly even chance – 50%

- Likely/probably – 60%

- Very likely/very probable – 80%

- Almost certainly – 100%

This threat assessment is based on information available as of 1 March, 2019.

Update on cyber threats to Canada's democratic process

Introduction

In June 2017, CSE released its assessment on Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process. The report looked at cyber threat activity directed at democratic processes around the world. The key judgements in that assessment remain valid today, including:

- Cyber threat activity is increasing around the world and Canada is not immune;

- A small number of nation-states have undertaken most cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide;

- At the federal level, political candidates, parties and voters – through online media platforms – are more vulnerable than elections themselves.

Since we published our June 2017 report, cyber threat activity against democratic processes has become even more prevalent worldwide. We assess that the likelihood of cyber threats targeting Canada’s democratic process during the 2019 federal election has increased.

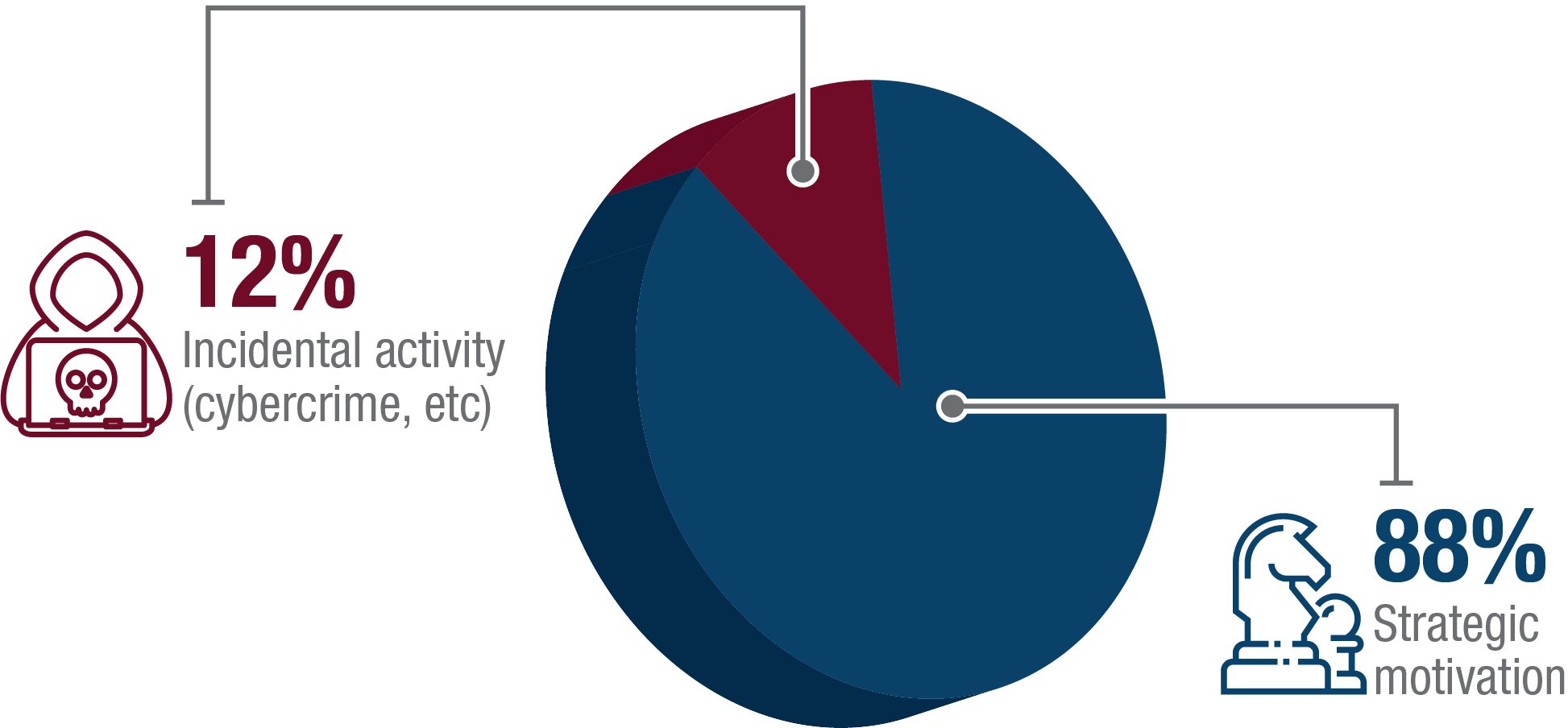

This update focuses on cyber threat activity undertaken by foreign adversaries with the intention of interfering with democratic processes. We distinguish these foreign adversaries from other threat actors, such as cybercriminals, who generally do not have the intention to interfere with democratic processes, but may do so incidentally as they pursue other objectives. While it is extremely difficult to measure the effect of cyber threat activity on the outcome of an election, even the perception of foreign interference can diminish trust in democracy.

Despite the increasing global cyber threat to democratic processes, there have been some positive developments since the publication of our 2017 assessment. Extensive media coverage and analysis of foreign cyber interference has greatly raised public awareness of the potential threat, as has more frequent reporting and public attribution of major cyber incidents by CSE and allies. Internet companies have indicated a willingness to reduce the illegitimate use of their platforms that could lead to foreign cyber interference.

Furthermore, in 2018, authorities charged individuals based in Russia with interfering in the 2016 United States presidential election, representing a shift from identifying and defending against malicious activity to confronting and prosecuting cyber threats to the democratic process in the United States.

Why target Canada's democratic process?

Canada in the world

Canada is a G7 country, a NATO member, and an active member of the international community. As a result, the choices that the Government of Canada makes about military deployments, trade and investment agreements, diplomatic engagements, foreign aid, or immigration policy are of interest to other states. Canada’s stance can affect the core interests of other countries, foreign groups, and individuals. Foreign adversaries may use cyber tools to target the democratic process to change Canadian election outcomes, policy makers’ choices, governmental relationships with foreign and domestic partners, and Canada’s reputation around the world.

Canada is online, as are foreign adversaries

Living in one of the most connected societies in the world, Canadians must be more vigilant against cyber tools than those in less connected nations. The vast majority of Canadians use the services provided by major Internet companies to obtain information, communicate with one another, and build communities.Endnote1 Foreign adversaries wanting to interfere with the democratic process in Canada may take advantage of our highly connected society and use cyber tools to amplify their interference activity in Canada.

Foreign adversaries have invested in cyber power

Cyber capabilities have become another means for nation states to further their interests around the world. Increasingly, foreign adversaries consider cyber power as a way of pursuing their strategic objectives: national security, economic prosperity, and even advancing a regime’s political and broader ideological goals. Foreign adversaries use cyber tools because they are relatively cheap and deniable ways to complement traditional diplomatic or military action or espionage.

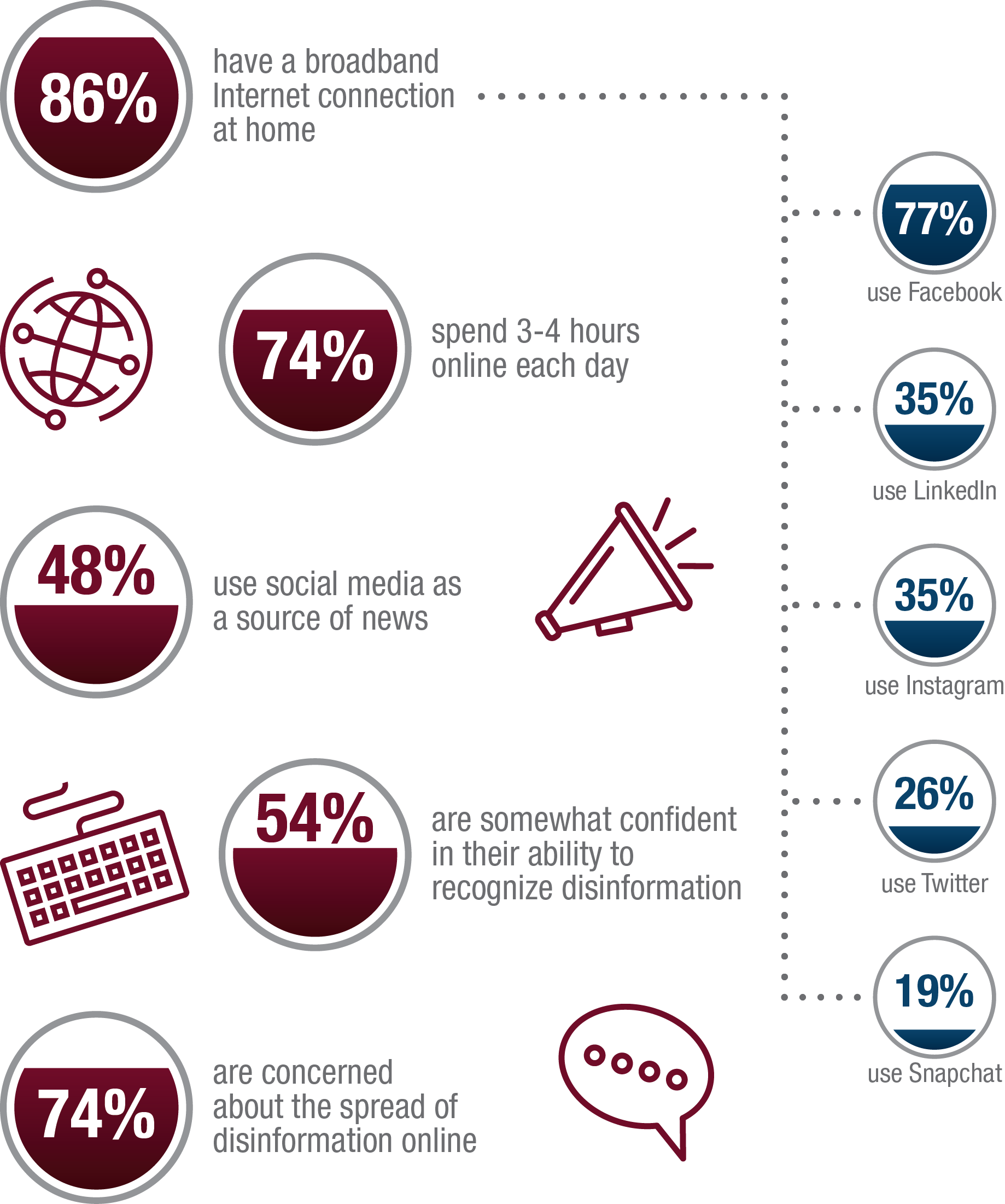

Figure 1: Canadians and the Internet (based on CIRA.CA dataEndnote2)

Long description

Canadians use the Internet a great deal in their lives and to access information according to the Canadian Internet Registry Authority: 86% have a broadband connection at home; 74% spend 3-4 hours online each day; 48% use social media as a source of news; 54% are somewhat confident in their ability to recognize disinformation; 74% are concerned about the spread of disinformation line; 77% use Facebook; 35% use LinkedIn; 35% use Instagram; 26% use Twitter; and 19% use Snapchat.

Possible effects of cyber threat activity against the democratic process

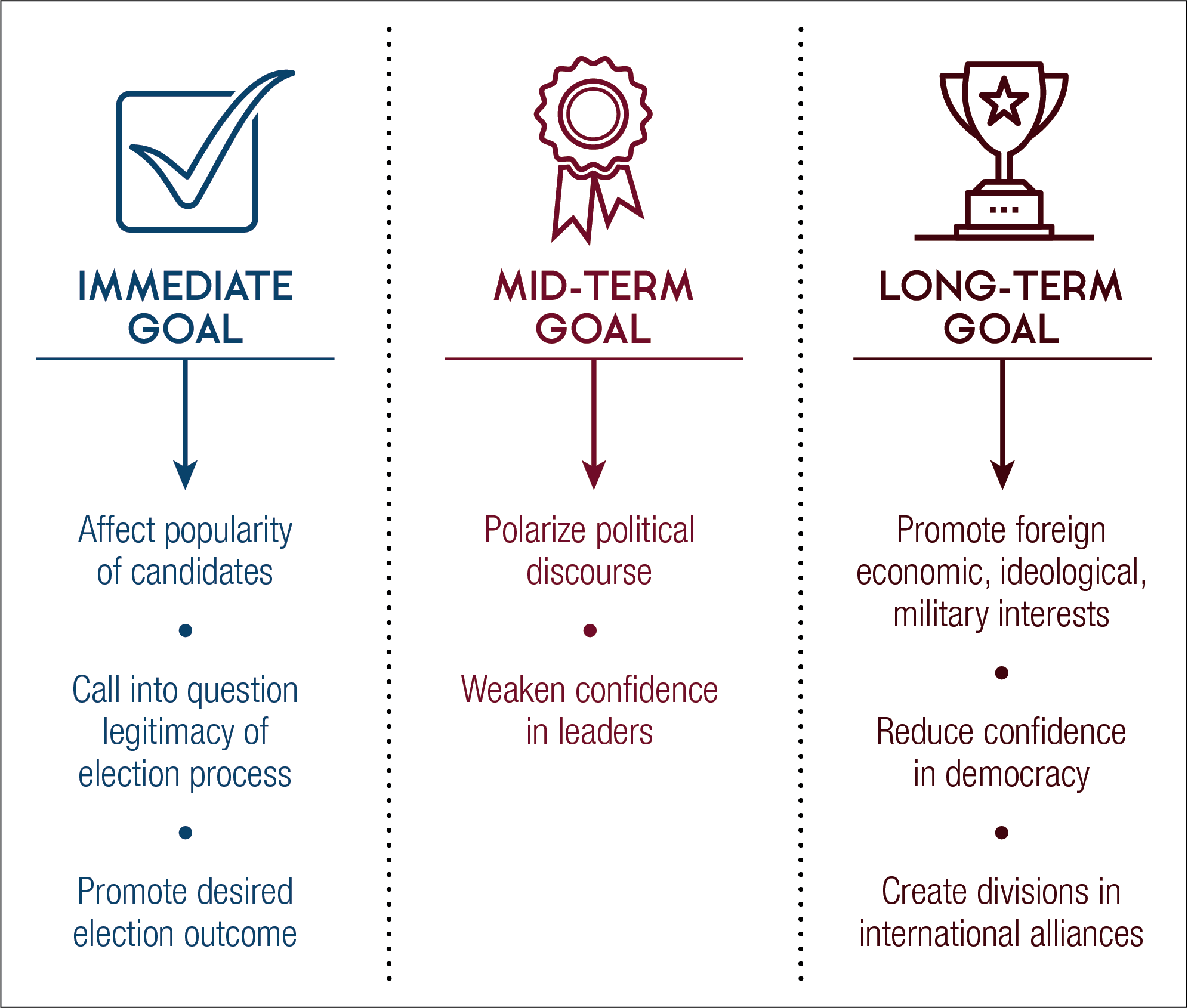

The short-term consequences include:

- Burying legitimate information or polarizing social discourse;

- Affecting the popularity of, or support for candidates;

- Calling into question the legitimacy of the election process;

- Promoting a desired election outcome; and

- Distracting voters from important election issues.

Cyber threat activity against the democratic process can also yield mid- and long-term consequences, including:

- Reducing the public’s trust in the democratic process;

- Polarizing social discourse;

- Creating divisions in international alliances;

- Weakening confidence in leaders;

- Dissuading qualified candidates from pursuing elected office; and

- Promoting foreign economic, geopolitical, or ideological interests

Figure 2: Why do nation-states use cyber capabilities to influence democratic processes of foreign countries?

Long description

There are three types of goals nation-states pursue when using cyber capabilities to influence democratic processes of foreign countries. Immediate goals include: to affect the popularity of candidates; to call into question the legitimacy of an election process; and to promote a desired outcome. Mid-term goals include: to polarize political discourse and to weaken confidence in leaders. Long-term goals include to promote foreign economic, ideological, or military interests; to reduce confidence in democracy; and to create divisions in international alliances.

Key targets of Canada's democratic process

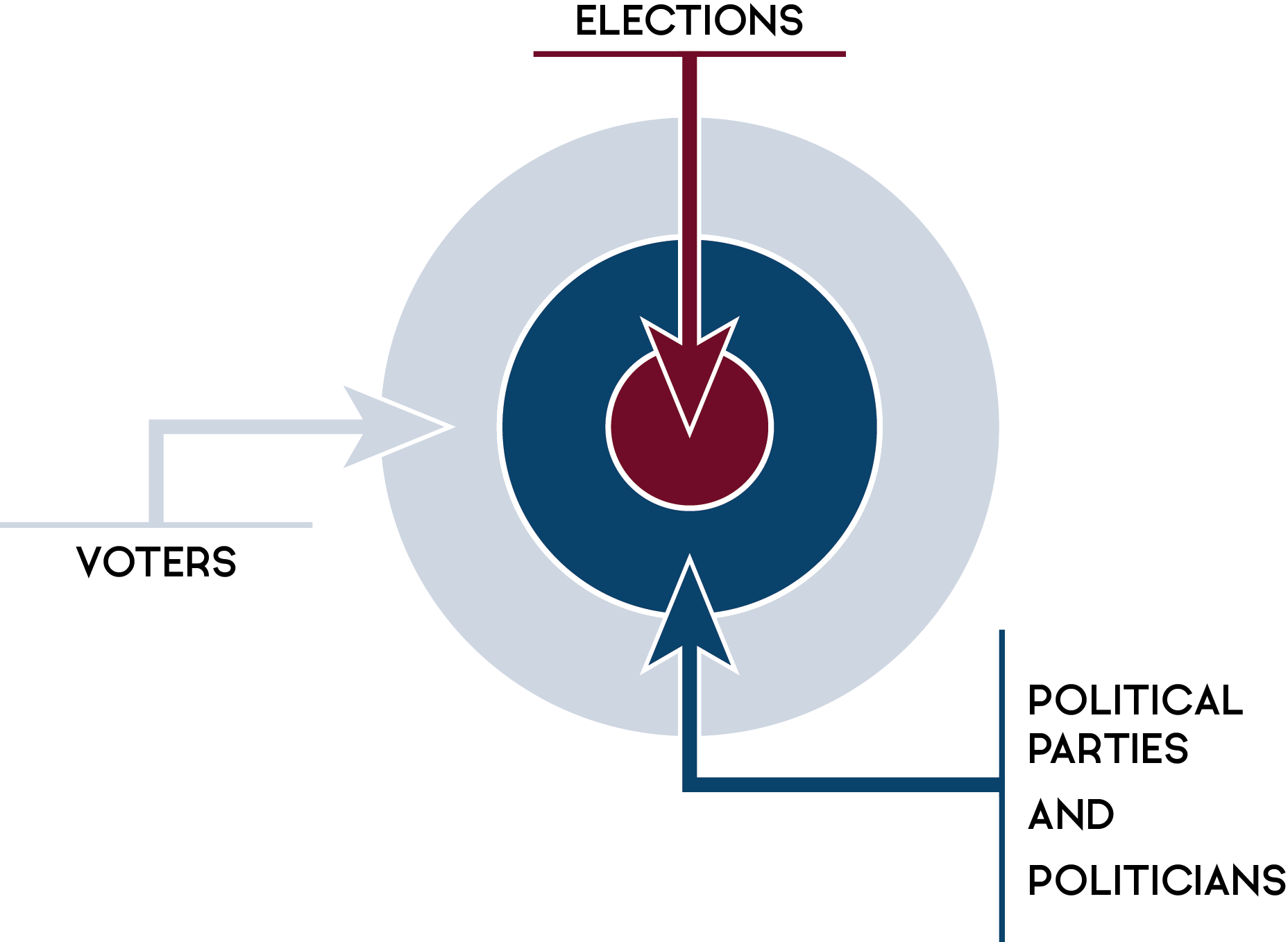

Cyber threat activity continues to target the three aspects of the democratic process

Voters engage with political parties, candidates, and other voters through traditional and social media. Cyber threat actors manipulate online information, often on social media using cyber tools, in order to influence voters’ opinions and behaviours. In the 2017 Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process we called this target “the media.” We have revised this term to focus less on the medium and more on the target itself: the voters.

Political parties, candidates, and their staff vie for attention and support in elections, relying heavily on the Internet, which they use to organize themselves and communicate with voters. Cyber threat actors use cyber tools to target the websites, e-mail, social media accounts, and the networks and devices of political parties, candidates, and their staff.

Elections include all the processes involved when Canadians vote for their Member of Parliament. For successful transitions of government to take place, Canadians must have confidence the process is legitimate. Cyber threat actors could attempt to undermine trust in our elections or suppress voter turnout by altering content on websites, social media accounts, and networks and devices used by Elections Canada.

Figure 3: Canada’s democratic process

Long description

There are three targets in Canada’s democratic process that cyber threat actors can try to affect: in the outer layer are voters, who represent the largest number of targets; in the middle layer are political parties and politicians; and in the centre of the target are elections.

Global trends and the threat to Canada

Global baseline of know events

Since issuing our 2017 report, CSE has continued to monitor cyber threat activity against democratic processes around the world. Given the covert nature of most cyber threat activity, there are likely incidents that we have not observed. We therefore assume that our data underestimates the total number of events.

As Figure 4 below illustrates, the vast majority of cyber threat activity affecting democratic processes around the world since 2010 has been strategic, meaning threat actors specifically targeted a national democratic process for the purpose of affecting the outcome. Most of the remainder of the cyber threat activity was cybercrime, such as stealing voter data in order to sell personal information or use it for criminal purposes.

Figure 4: Global cyber threat activity affecting a democratic process (2010-2018)

Long description

Strategically motivated activity represents the majority of cyber threat activity against the democratic process in our period of observation, 2010-18. The remaining 12% of cases are incidental activity, such as cybercrime.

We observe four key trends from recent global cyber threat activity against democratic processes

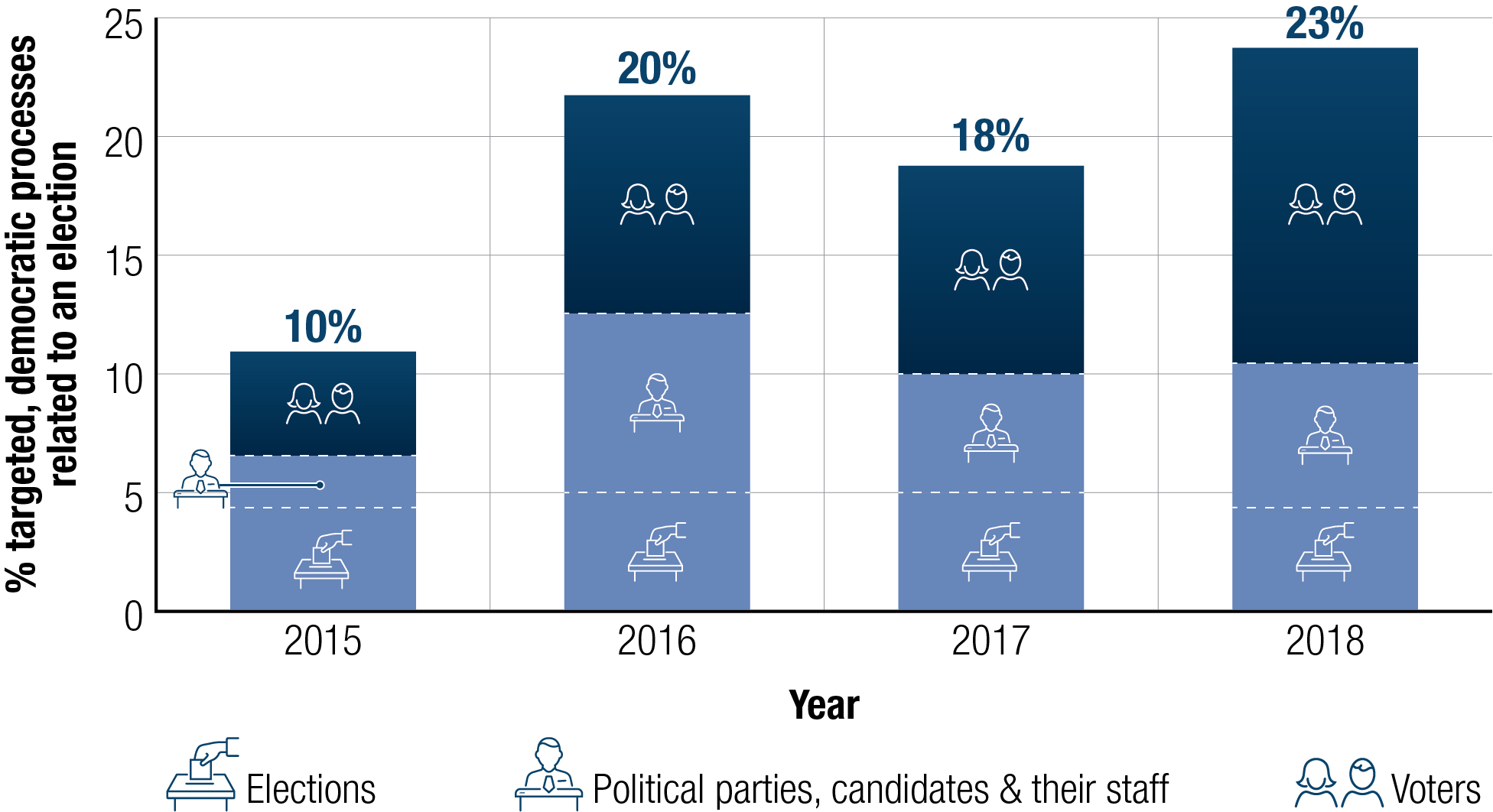

Trend 1: Cyber threat activity against democratic processes is increasing worldwide

The proportion of national elections targeted by foreign cyber threat activity has more than doubled since 2015. When looking at economically advanced democracies similar to Canada, such as members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), Figure 5 below shows that the proportion of elections targeted by cyber threat activity has more than tripled. In fact, half of all OECD countries holding national elections in 2018 had their democratic process targeted by cyber threat activity.

Figure 5: Cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes related to an election increasing

Long description

Cyber threat activity related to an election is represented according to worldwide incidents and its subset, activity in countries that are members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) from 2015 to 2018.

- In 2015, 10% of countries around the world and 15% of OECD countries experienced cyber threat activity related to an election.

- In 2016, 20% of countries around the world and 30% of OECD countries experienced cyber threat activity related to an election.

- In 2017, 18% of countries around the world and 44% of OECD countries experienced cyber threat activity related to an election.

- In 2018, 23% of countries around the world and 50% of OECD countries experienced cyber threat activity related to an election.

These findings uphold the forecast we made in 2017, which anticipated increasing cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide. In the 2018 National Cyber Threat Assessment, CSE noted that cyber tools are an attractive option for adversaries because:

- Nation-states have continued investing in their cyber programs;

- Attributing and deterring cyber threat activity remains difficult;

- There is a copycat dynamic whereby successful cyber threat activity inspires similar activity; and

- Cybercrime marketplaces provide cheap and easy-to-use cyber tools.

The increase in cyber threat activity has occurred despite important countervailing trends, such as greater media coverage and public awareness, improved cyber security practices, and public attribution and legal indictments against threat actors. We judge that while it is likely these trends have raised the costs for cyber threat actors seeking to target democratic processes, the cost is still not high enough for cyber threat actors to abandon their activities.

Trend 2: Cyber threat activity against democratic processes increasingly targets voters

Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms protects the freedom of expression, including the vast majority of online information. The problem, however, is that foreign adversaries have developed cyber tools to manipulate information on the Internet and carry out interference activities at scale and with precision. They have used these methods to interfere with democratic processes around the world.

Figure 6: Cyber threat activity targeting voters increasing worldwide

Long description

Cyber threat activity targeting voters is increasing around the world.

- In 2015, 10% of countries around the world experienced cyber threat activity related to an election: 4% targeted voters; 2% targeted political parties, candidates, and their staff; and 4% targeted elections.

- In 2016, 20% of countries around the world experienced cyber threat activity related to an election: 9% targeted voters; 7% targeted political parties, candidates, and their staff; and 5% targeted elections.

- In 2017, 18% of countries around the world experienced cyber threat activity related to an election: 8% targeted voters; 5% targeted political parties, candidates, and their staff; and 5% targeted elections.

- In 2018, 23% of countries around the world experienced cyber threat activity related to an election: 13% targeted voters; 6% targeted political parties, candidates, and their staff; and 4% targeted elections.

As Figure 6 shows, voters now represent the single largest target of cyber threat activity against democratic processes, accounting for more than half of global activity in 2018. This shift seems to have started in 2016, which is likely due in part to the perceived success among cyber threat actor.

Most foreign adversaries weigh the costs and benefits of possible cyber threat activities before undertaking them. It is likely that they perceive targeting voters to be a more effective or efficient way to interfere with democratic processes than targeting elections, or political parties, candidates, and their staff.

Factors that contribute to the increase in voter targeting very likely include:

- Voters rely on the Internet, including social media, as a key source of information;Endnote3

- False and misleading information, often spread through cyber tools, can be difficult to distinguish from trustworthy and reliable information and sources,Endnote4 legitimate advertising, and other forms of protected speech;Endnote5 and

- A perception by cyber threat actors that targeting voters is low-cost and low-risk.

Trend 3: Cyber threat activity persists against political parties, condidates, and their staff

Globally, political parties, candidates, and their staff remain attractive targets for cyber threat activity, accounting for a tenth of cyber threat activity against democratic processes in advanced democracies (OECD countries) in 2018. Threat actors target political parties, candidates, and their staff in different ways. They may steal information and then release it to the public for the purpose of embarrassing or discrediting the political party or candidate. In order to enhance this effect, a threat actor may modify information before releasing it to the public.

Another way threat actors can target political parties and candidates is by obtaining private information through cyber espionage, and then trying to influence the individual through blackmail, bribery, or coercing the target into behaviours or activities that would otherwise not occur.

Foreign adversaries may steal voter or party databases because they fetch a price on illicit areas of the Internet, where large quantities of personal identity information are constantly bought and sold. They can steal sensitive campaign documents and communications and sell or release them. And they can disrupt or destroy a party’s information, networks and devices using malware, such as ransomware.

New technology has created an emerging threat called deep fakes, which are synthetic videos often indistinguishable from real footage. Foreign adversaries can use this new technology to try to discredit candidates, and influence voters by, for example, creating forged footage of a candidate delivering a controversial speech or showing the candidate in embarrassing situations.

Improvements in artificial intelligence (AI) are likely to enable interference activity to become increasingly powerful, precise, and cost-effective. Evolving technology underpinned by AI, such as deep fakes, will almost certainly allow threat actors to become more agile and effective when creating false or misleading content intended to influence voters, and make foreign cyber interference activity more difficult to detect and mitigate.

Figure 7: A selection of recently observed global cyber threat activity against political parties

Long description

There are a variety of cyber threat activities observed against political parties, including: stealing sensitive campaign documents, stealing a party’s voter information, releasing unauthorized information, and impeding a party’s use of its devices and networks.

Trend 4: Elections continue to be targeted by cyber threat activity, though less frequently than voters, political parties, condidates, and their staff

Cyber threat activity targeting election processes continues to occur, accounting for slightly less than a fifth of all cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide in 2018. In general, cyber threat actors could try to affect voter eligibility, ballot casting on election day, the counting and recording of votes, and the dissemination of results to the public.

The most common cyber threat activities noted to date affect election agency websites, or involve the theft of a voter database. In carrying out these activities, foreign adversaries generally attempt to sow doubt about the validity of an election result, rather than covertly change the result.

Cyber threat activity very rarely affects the IT systems that electoral agencies use for recording, storing, and transmitting election data, such as the vote count. Such activity accounted for less than four percent of all cyber threat activity against elections globally in 2018. Cyber threat actors very likely see changing a vote count in a national election as difficult and very likely consider it impossible against elections that use hand-counted paper ballots, such as the Canadian federal election.

Cyber Espionage Against Political Parties in Australia

A cyber threat actor compromised the information systems of Australia’s parliament and three major political parties in February 2019, a year in which Australia will hold national elections. The Australian Prime Minister noted that Australia’s “cyber experts believe that a sophisticated state actor is responsible for this malicious activity.” The case highlights that the information of democratic institutions, including political parties, represents an attractive target for state-sponsored cyber threat activity in an election year.Endnote6

Canadian context

Foreign influence and interference outside the election period

Since the 2015 federal election, Canadian political leaders and the Canadian public have been targeted by foreign cyber interference activities. For example:

- More than one foreign adversary has manipulated social media using cyber tools to spread false or misleading information relating to Canada on Twitter, likely to polarize Canadians or undermine Canada’s foreign policy goals;

- Foreign state-sponsored media have disparaged Canadian cabinet ministers;Endnote7 and

- A foreign adversary has manipulated information on social media to amplify and promote viewpoints highly critical of Government of Canada legislation imposing sanctions and banning travel of foreign officials accused of human rights violations.Endnote8

Techniques used by foreign adversaries to undertake cyber interference on Twitter

Foreign adversaries hijack other users’ accounts or build Twitter personas by using new accounts that tweet about popular and uncontroversial subjects in order to build followings and credibility so that they can reach broader audiences when they broadcast false and misleading information and other content designed to influence opinions. These accounts appear normal, typically gaining friends and followers by sharing material about sports or entertainment. However, these accounts then switch to political messaging with Canadian themes following international events involving Canada.

Forecast of foreign interference during the 2019 election

We assess that an increasing number of foreign adversaries have the cyber tools, the organizational capacity and a sufficiently advanced understanding of Canada’s political landscape to direct cyber interference during the 2019 federal election, should they have the strategic intent.

Even if a foreign adversary does develop strategic intent to interfere with Canada’s democratic process, we consider foreign cyber interference of the scale of Russian activity against the 2016 United States presidential election improbable at this time in Canada in 2019. However, we judge it is very likely that Canadian voters will encounter some form of foreign cyber interference ahead of, and during, the 2019 federal election.

False report about Canadian troops

In 2016, false information appeared on social media about a “failed Canadian raid” on Russian separatist positions in Ukraine, alleging that 11 Canadian military personnel had been killed. Users shared an Englishlanguage version of this fictional report over 3,000 times on Facebook. A similar false report about three Canadian soldiers dying after their vehicle hit a landmine in Ukraine spread on pro- Russian websites in May 2018.Endnote9The authors of the false reports likely intended to portray Canadian troops – who are present in Ukraine in non-combat roles – as reckless and ineffective in their operations.

We judge it highly likely that foreign cyber interference against Canada would resemble the cyber interference campaigns undertaken against other advanced democracies in recent years. Foreign adversaries have attempted to sway the ideas and decisions of voters by focusing on polarizing social and political issues, promoting the popularity of one party over another, or trying to shape the public statements and policy choices of a candidate using cyber tools or social media platforms.

The Canadian federal election is paper-based, and Elections Canada has a number of legal, procedural, and IT measures in place that provide very robust protections against attempts to covertly change the official vote count in Canada.

It is likely, however, that adversaries will try to deface a website or steal personal information that could be used to send out incorrect information to Canadians, causing an inconvenience or disruption to the election process. The aim of such activity would be to sow doubt among voters, causing them to question the legitimacy of the election. This activity may even discourage certain voters from participating in the democratic process entirely.

Internet research agency

Russia’s Internet Research Agency (IRA) continues to create illegitimate websites to host false and misleading information framed as independent online journalism or personal blogs. Botnet accounts rally to automatically spread and promote the information, which often consists of a headline and a hyperlink, across various social media platforms. This covertly promoted false and misleading information ends up in the feeds of genuine users, most of whom are likely unaware of its malicious origin and deceptive intent. IRA employees use fabricated accounts and botnets to engage genuine users and defend the authenticity of IRA content.

The IRA-linked website ReportSecret.com automatically disseminated and illicitly amplified Canadian-themed articles on Twitter. One campaign in September 2017 attempted to replicate the political discord surrounding protests in the American National Football League in a Canadian context by promoting headlines such as “The Canadian Football League is Protesting THEIR OWN National Anthem!” and “Canadian NHL Player CONSIDERING ‘Taking a Knee’ During U.S. Anthem.”

Looking ahead

The Government of Canada recently announced the creation of a Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force, comprised of officials from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), Global Affairs Canada, and CSE. In anticipation of the 2019 election, the SITE Task Force will help the government assess and respond to foreign threats.

CSE will assist Canadian political parties and elections administrators, as appropriate. CSE, in coordination with its Cyber Centre, has offered to provide cyber security advice and guidance to all major political parties, in part through a Cyber Security Guide for Campaign Teams. CSE will continue to work closely with Elections Canada to protect its infrastructure.

We encourage Canadians to consult the Cyber Centre’s online brochure for cyber security advice and guidance, and social media tips. CSE’s Get Cyber Safe campaign will also continue to publish relevant advice and guidance on www.getcybersafe.gc.ca in advance of the 2019 Federal Election.