Alternate format: Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process : July 2021 update (PDF, 16 MB)

Communications Security Establishment

Ottawa, ON K1J 8K6

ISSN: 2563-8165

Cat: D95-10E-PDF

Cyber Threats to Canada’s Democratic Process is an ad hoc document published approximately every two years

Table of contents

- About us

- Executive summary

- About this document

- Introduction

- Key targets in the democratic process

- Global trends

- Global baseline of known events

- Trend 1 — State-sponsored cyber threat activity focuses on specific states and regions

- Trend 2 — Most cyber threat activity against democratic processes supports strategic objectives

- Trend 3 — Targeting of democratic processes remains high

- Trend 4 — Cyber activity frequently impacts multiple targets within the democratic process

- Global baseline of known events

- Canadian context

- Conclusion

- Endnotes

List of figures

- 01 Frequency of social media use by adults, 2020

- 02 Short-, medium-, and long-term goals of state-sponsored cyber actors

- 03 Three components of online foreign influence activity

- 04 Political campaigning during the COVID-19 pandemic

- 05 How candidates adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic

- 06 Cyber threat actors target strategically significant states and regions

- 07 Strategic and incidental objectives

- 08 Cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes related to an election

- 09 Cyber threat activity can impact multiple targets

- 10 Democratic processes related to elections targeted worldwide, 2015–2020

- 11 Technology in Canadian elections

- 12 Canadians on Twitter

- 13 Measures to protect Canada's democratic process

About us

The Communications Security Establishment (CSE) is Canada’s centre of excellence for cyber operations. As one of Canada’s key security and intelligence organizations, CSE protects the computer networks and information of greatest importance to Canada and collects foreign signals intelligence. CSE also provides assistance to federal law enforcement and security organizations in their legally authorized activities when they need CSE’s unique technical capabilities.

CSE protects computer networks and electronic information of importance to the Government of Canada, helping to thwart state-sponsored or criminal cyber threat activity on our systems. In addition, CSE’s foreign signals intelligence work supports government decision-making in the fields of international affairs, defence, and security, providing a better understanding of global events and crises and helping to further Canada’s national interest in the world.

As part of CSE, the Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (Cyber Centre) is home to trusted experts in cyber security with a straightforward, focused mandate to collaborate with government, the private sector, and academia to make Canada a safer place online.

CSE and its Cyber Centre play an integral role in helping to protect Canada and Canadians against foreign‑based terrorism, foreign espionage, cyber threat activity, kidnapping of Canadians abroad, attacks on our embassies, and other serious threats with a significant foreign element, helping to ensure our nation’s security, stability, and prosperity.

Executive summary

Democratic processes around the world continue to be targeted by cyber threat actors. In this assessment, we review global trends in cyber threat activity against democratic processes (which we define as including voters, political parties, and elections) and evaluate the threat to Canada, with special focus on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key findings:

Global trends

- Democratic processes remain a popular target. After increasing from 2015 to 2017, the proportion of democratic processes targeted by cyber threat actors has remained relatively stable since 2017.

- From 2015 to 2020, we judge that the vast majority of cyber threat activity affecting democratic processes can be attributed to state-sponsored cyber threat actors. These actors target democratic processes in pursuit of their strategic objectives (i.e., political, economic, and geopolitical).

- Russia, China, and Iran are very likely responsible for most of the foreign state-sponsored cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide.

- Cyber threat actors most often target some combination of voters, political parties, and election infrastructure. We judge that cyber threat actors likely perceive that directing their efforts at a combination of targets associated with a democratic process is more effective than targeting one group in isolation.

- Between 2015 and 2020, cyber threat activity was directed at voters more often than against political parties and elections. This activity included online foreign influence activity as well as more traditional cyber threat activities, like information theft or denying access to important websites. We assess that it is likely that cyber threat actors perceive targeting voters to be a more effective and relatively easy way to interfere with democratic processes.

- We assess that changes made around the world in response to the COVID‑19 pandemic, such as moving parts of the democratic process online or incorporating new technology into the voting process, almost certainly increased the cyber threat surface of democratic processes. Most significantly, threat actors can harness and amplify false narratives related to the COVID‑19 pandemic to decrease confidence in elections.

Implications for Canada

- We assess that Canada's democratic process remains a lower-priority target for state-sponsored cyber actors relative to other countries. However, we judge it very likely that Canadian voters will encounter some form of foreign cyber interference (i.e., cyber threat activity by foreign actors or online foreign influence) ahead of, and during, the next federal election. It is unlikely to be at the scale seen in the US.

- In the event of a federal election during a pandemic, Elections Canada has plans in place to protect the health and safety of all participants in the electoral process. While any modifications to the electoral process have the potential to increase the cyber threat, we assess that the planned changes do not substantially expand the cyber threat to Canada’s democratic process.

About this document

This document provides an update to the 2017Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process reports and 2019 Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process reports released by CSE. Its purpose is to inform Canadians about cyber threats to the democratic process.

Scope

This report considers cyber threat activity that affects the democratic process, which we view as a combination of voters, political parties, and elections. Cyber threat activity involves the use of cyber tools (e.g., malware and spear-phishing) to compromise an information system by altering the confidentiality, integrity, and availability of a system or the information it contains. This type of activity is conducted by state-sponsored actors, cybercriminals, hacktivists, politically motivated actors, and thrill-seekers. There is a significant amount of false and misleading information online, but this assessment primarily considers online foreign influence activity targeting voters. This influence activity happens when foreign threat actors covertly manipulate online information, often using cyber tools, in order to influence voters’ opinions and behaviours. We define foreign interference as covert, deceptive, or coercive activity by a foreign actor against a democratic process, conducted to advance strategic objectives. Foreign cyber interference includes cyber threat activity by foreign actors as well as online foreign influence activity. Note that these definitions are specific to our focus on cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process and that similar definitions can be used differently by other Canadian federal institutions.

Sources

In producing this document, we relied on reporting from both classified and unclassified sources. CSE’s foreign intelligence mandate provides us with valuable insights into adversary behaviour. Defending the Government of Canada’s information systems also provides CSE with a unique perspective to observe trends in the cyber threat environment.

Limitations

We discuss a wide range of cyber threats to global and Canadian political and electoral activities based on our access to information. Providing threat mitigation advice is outside the scope of this document.

More information

For readers interested in more detailed information about cyber tools and the evolving cyber threat landscape, we refer you to the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020 and An Introduction to the Cyber Threat Environment.

Further resources from the Cyber Centre are available online, including Get Cyber Safe, Don’t Take the Bait: Recognize and Avoid Phishing Attacks, and Cyber Hygiene.

Estimative language

Long description - Estimative language

Chart pairing estimative language with percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

- Almost no change – 0%

- Very unlikely/very improbable – 20%

- Unlikely/improbable – 40%

- Roughly even chance – 50%

- Likely/probably – 60%

- Very likely/very probable – 80%

- Almost certainly – 100%

Our judgements are based on an analytical process that includes evaluating the quality of available information, exploring alternative explanations, mitigating biases, and using probabilistic language. We use terms such as “we assess” or “we judge” to convey an analytic assessment. We use qualifiers such as “possibly”, “likely”, and “very likely” to convey probability.

The contents of this document are based on information available as of 12 July 2021.

The chart below matches estimative language with approximate percentages. These percentages are not derived via statistical analysis, but are based on logic, available information, prior judgements, and methods that increase the accuracy of estimates.

Introduction

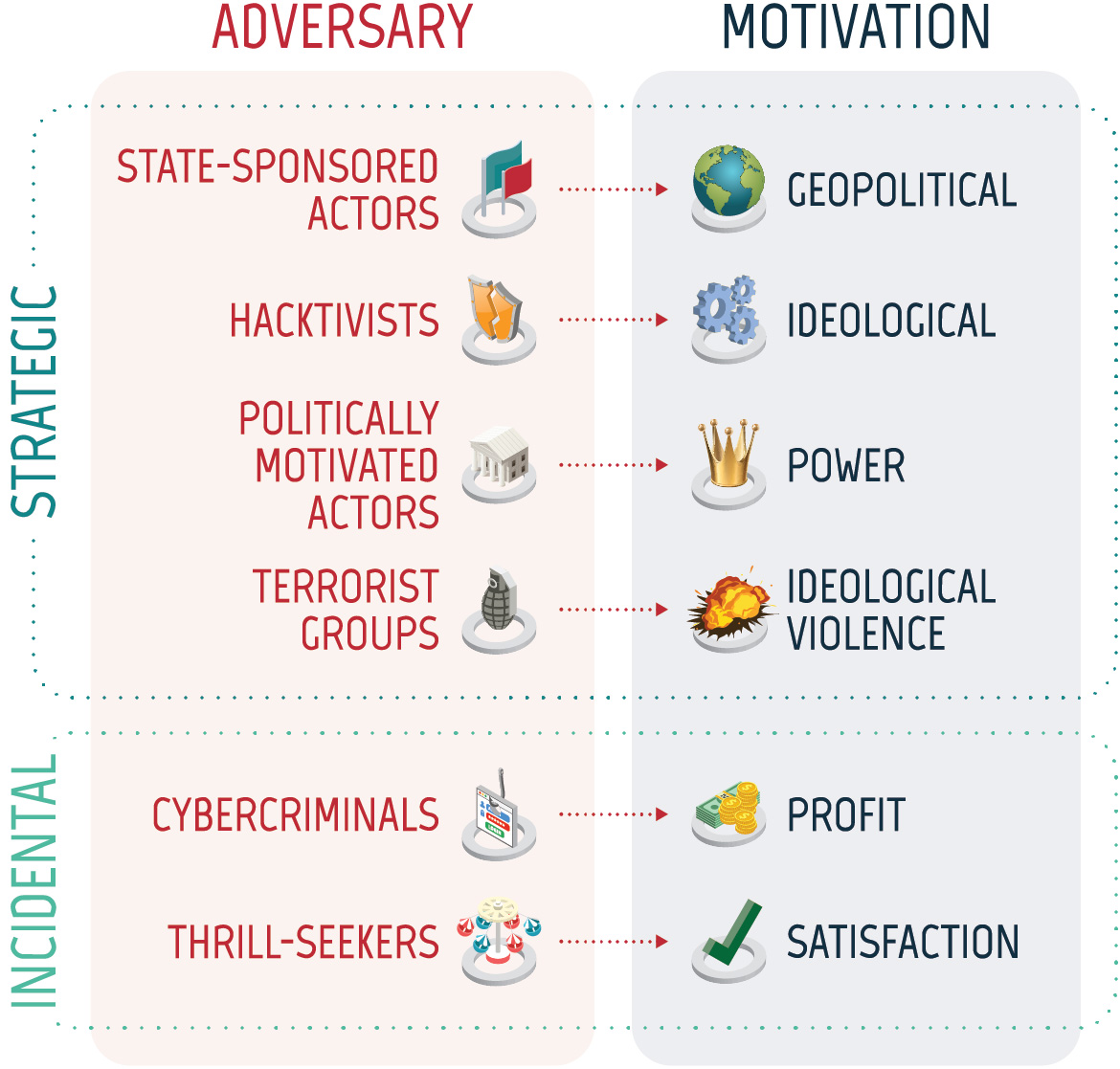

Around the world, democratic processes continue to be affected by cyber threat activity. A democratic process is made up of participants, like voters and political parties, and events, like elections. Cyber threat activity is carried out against these participants and events by state‑sponsored actors, cybercriminals, politically motivated actors, hacktivists, and thrill‑seekers. We have observed how the tactics these threat actors use have evolved over time as they adapt to emerging opportunities and new cyber tools that make it easier to target the democratic process.

Targeting democratic processes largely remains a strategic activity. State‑sponsored cyber threat actors with links to Russia, China, and Iran have conducted most of the observed cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide.

The COVID-19 pandemic has caused significant changes to how democratic processes operate around the world, including in Canada. In many jurisdictions, political parties and candidates have moved their campaigns almost entirely online. Electoral bodies responsible for elections have been forced to plan and prepare for elections while working from home. Voting procedures have also been adapted to ensure that the health of voters and poll workers is protected and that all eligible members of a society are able to vote safely. Yet, we judge that COVID‑19‑related changes to electoral procedures have had limited impacts on observed cyber threat activity against elections.

However, we have seen that COVID‑19‑related changes to elections, such as more people choosing to vote by mail or delays in the dissemination of results, have spurred falsehoods and conspiracy theories that call into question the legitimacy of election results. This is happening at a time when the online information ecosystem is already rife with false and misleading content. Both foreign and domestic actors create and share falsehoods for political or geopolitical gain or to manipulate or harm their target audience and society. Others share the content because they believe it to be true. It is increasingly difficult to determine who is sharing false information and why. In this environment, it is easier for hostile foreign actors to conduct online influence activity, fuel divisions within society, and undermine confidence in democratic institutions.

While there are many opportunities for threat actors to target democratic processes, it is important to note that, in the past few years, there have also been significant strides towards protecting democracy around the world. This includes efforts by governments, non-governmental and research organizations, civil society, traditional media, and social media and technology companies to improve cyber security practices, raise awareness, and respond to incidents quickly. For example, Canada has implemented a broad suite of measures, including legislation (i.e., the Elections Modernization Act), agreements with social media companies, as well as several initiatives to improve communication and information sharing between Elections Canada, Canadian security and intelligence agencies, other government departments, political parties, and voters.

In this assessment, we evaluate the cyber threats directed at democratic processes around the world and assess what this means for Canada, with special focus on the impacts of COVID‑19. First, we describe why an adversary would target Canada, discuss the possible consequences of cyber activity against democratic processes, and give an overview of the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on this threat. Next, we describe the cyber threats to voters, political parties, and elections around the world in more detail. Finally, we discuss global trends in cyber activity against democratic processes and what this means in the Canadian context.

Why target Canada’s democratic process?

Canada in the world

Canada takes an active role in the international community, participating in key multilateral forums, including the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the Organisation for Economic Co‑operation and Development (OECD), the Group of 20 (G20), and the Group of 7 (G7).Footnote 1 Government of Canada foreign policy, military deployments, trade and investment agreements, diplomatic engagements, international aid, and immigration policy are of interest to other states. Canada’s stance on an issue can affect the core interests of other countries, foreign groups, and individuals. Threat actors may use cyber tools to target Canada’s democratic process to change election outcomes, influence policy makers’ choices, impact governmental relationships with foreign and domestic partners, and impact Canada’s reputation around the world.

Canada is online, as are threat actors

According to the most recent estimates, approximately 94% of Canadians were using the Internet in 2021.Footnote 2 The vast majority of Canadians use the services provided by major Internet companies, such as Facebook or Google, to obtain information, communicate with one another, and build communities. As Canadians engage with each other and access information online, they become exposed to cyber threat actors and the tools they use to interfere with democratic processes. Threat actors who want to interfere with Canadian democratic processes may take advantage of Canada’s highly connected society and regularly used online services. Cybercriminals trying to make money and thrill-seekers searching for a challenge or notoriety may target Canadian democratic processes as well. While these activities lack a strategic agenda, they still impact the functioning of democratic processes and voters’ perceptions of the security, legitimacy, and fairness of the results.

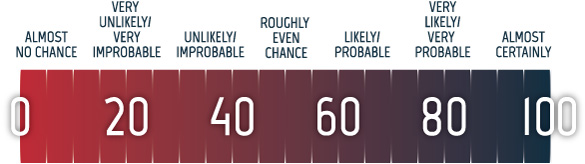

Figure 01: Frequency of social media use by adults, 2020

Long description - Frequency of social media use by adults, 2020

Bar chart showing statistics on the frequency of Canadian social media use by adults from 2020. This includes icons for the different social media platforms. The data is in the table below:

| Social Media Platform | Total Percentage of Canadian Adults Using the Platform | Percentage of Canadian Adults Using the Platform Daily | Percentage of Canadian Adults Using the Platform Weekly | Percentage of Canadian Adults Using the Platform Less Often |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 83% | 63.91% | 12.45% | 6.64% | |

| Messaging Apps | 64% | 44.85% | 13% | 6.5% |

| YouTube | 63% | 40.96% | 16.64% | 5.76% |

| 52% | 35.19% | 10.2% | 6.12% | |

| Linkedln | 44% | 11.88% | 14.08% | 17.6% |

| 42% | 21% | 9.6% | 10.92% | |

| 40% | 12.8% | 13.6% | 13.6% | |

| Snapchat | 27% | 15.39% | 6.21% | 5.4% |

| 15% | 8.1% | 4.05% | 2.85% | |

| TikTok/Douyin | 15% | 9.45% | 3.15% | 2.4% |

Data is from: “The State of Social Media in Canada 2020: A New Survey Report from the Ryerson Social Media Lab.” Ryerson University. 13 July 2020. https://socialmedialab.ca/2020/07/13/the-state-of-social-media-in-canada-2020-a-new-survey-report-from-the-ryerson-social-media-lab.

A Google search bar with the text: Google maintained 91.83% of the search engine market in Canada in January 2021.*

* Information from: “Search Engine Market Share Canada.” GlobalStats. Accessed February 2021. https://gs.statcounter.com/search-engine-market-share/all/canada.

An image of a smart phone with a magnet pointing towards three people on their phones accompanies the following information:

Of Canadian adults online in 2020, 94% of Canadians had a social media account on at least one platform.

An image of a pie chart with a Facebook like icon and an image of calendar icons showing seven days of the week accompany the following information:

Of Canadian adults online in 2020, 83% had a Facebook account and 77% of those used Facebook daily.

These two statements are based on: “The State of Social Media in Canada 2020: A New Survey Report from the Ryerson Social Media Lab.” Ryerson University. 13 July 2020. https://socialmedialab.ca/2020/07/13/the-state-of-social-media-in-canada-2020-a-new-survey-report-from-the-ryerson-social-media-lab.

Cyber tools and services improving and widely available to threat actors

In the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2020 (NCTA 2020), we assessed that the development of commercial markets for cyber tools and talent has reduced the time it takes for states to build cyber capabilities and increased the number of states with cyber programs. As more states have access to cyber tools, states that were interested in targeting democratic processes, but previously lacked sufficient capabilities, can now more readily undertake this type of cyber activity. The proliferation of state cyber programs also makes it more difficult to identify, attribute, and defend against cyber threat activity more broadly.

In addition, a large illegal market for cyber tools and services is greatly reducing the start-up time for cybercriminals and enabling them to conduct more complex and sophisticated campaigns.Footnote A Many online marketplaces allow vendors to sell specialized cyber tools and services that users can purchase and use to commit cybercrimes, including website defacement, cyber espionage, distributed denial of service (DDoS) attacks, and ransomware attacks.Footnote B Any of these tools could be used against democratic processes for financial gain, to send a political message, or to attempt to impact an election.

Deepfakes: beyond images and video

Evolving technology underpinned by artificial intelligence (AI) used by cyber threat actors to create false or misleading online content has become cheaper and easier to access.Footnote 3 In NCTA 2020, we discussed deepfake videos and how they can be used to create synthetic videos of events or public figures that look real. While technology companies have invested resources in advancing methods to automatically detect deepfake videos, other rapidly evolving forms of AI-generated media have emerged that are harder to detect, such as AI-generated writing (i.e., deepfake text) and deepfake audio.Footnote 4 Threat actors can use deepfake text against electoral processes, including targeting voters with disinformation, spear-phishing candidates and their staff, and abusing online governmental processes.Footnote 5 Deepfake text is now largely undetectable by humans. A 2019 study found that when humans were asked to classify deepfake comments as human or bot submissions, the results were no better than the results of random guessing.Footnote 6 Threat actors can also target voters using AI-generated audio to mimic the tone, inflection, and idiosyncrasies of candidates or poll workers.

Effects of cyber activity against democratic processes

Cyber threat activity against democratic processes around the world can have short-, mid-, and long-term effects. In some cases, the perception of successful cyber threat activity against democratic processes can undermine public confidence in democratic institutions, even if the cyber activity never occurred or had no significant consequences. For example, the US Intelligence Community found that during the 2020 US presidential election some foreign actors spread false or inflated claims about alleged compromises of voting systems to undermine confidence in the electoral process and results.Footnote 7 Many allegations of election fraud surfaced in relation to the 2020 US election and continued to persist even after they were proven false.Footnote 8 These allegations have had lasting implications for trust in democratic processes in the US.Footnote 9

When cyber threat activity against political parties or election infrastructure is combined with online foreign influence activities, these impacts can be greater. For example, cyber threat actors can steal sensitive information about a candidate and spread the stolen information on social media to decrease support for that candidate.

The short-term consequences of cyber threat activity include:

- amplifying false or polarizing discourse;

- burying legitimate information;

- affecting the popularity of or support for candidates;

- calling into question the legitimacy of the election process and results;

- promoting a desired election outcome;

- distracting voters from important election issues; and

- reducing voter turnout.

Mid-term and long-term consequences include:

- reducing the public’s trust in the democratic process;

- lowering trust in journalism and the media;

- creating divisions in international alliances;

- increasing polarization and decreasing social cohesion;

- weakening confidence in leaders; and

- promoting the economic, geopolitical, or ideological interests of hostile foreign states.

Figure 02: Short-, medium-, and long-term goals of state-sponsored cyber actors

Long description - Short-, medium-, and long-term goals of state-sponsored cyber actors

- Short-term Goals

- Call into question legitimacy of election process

- Amplify false or polarizing discourse

- Reduce voter turnout

- Medium-term Goals

- Polarize political discourse

- Weaken confidence in leaders

- Long-term Goals

- Reduce confidence in democracy

- Promote foreign economic, ideological, or military interests

- Create divisions in international alliances

The Short-, Medium-, and Long-term Goal headings are accompanied by images of a ballot box with an increasingly torn maple leaf on the front and an icon in the upper left-hand corner. The Short-term subheading has a slightly torn maple leave and an hourglass icon. The Medium-term subheading has a half torn maple leaf and a clock icon. The Long-term subheading has a fully torn maple leaf and an icon of a calendar with a bullseye on it.

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on democratic processes

In 2020, at least 40 countries and territories around the world postponed national-level elections and referendums due to the COVID-19 pandemic. At least 79 national-level elections and referendums were held during the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 10 Most states implemented sanitary and distancing measures and many created additional ways to vote, allowing those in self-isolation or at higher risk to vote more safely and reducing crowding at in-person voting locations. For example, states expanded mail-in voting, enabled voting over the phone, and expanded voting hours and locations.Footnote 11

Overall, the changes to electoral procedures due to COVID-19 appear to have had limited impacts on the cyber threat to elections. While these changes created additional opportunities for cyber threat actors, we did not observe a substantial change to the frequency of their activities. While threat actors can try to disrupt information about changes to voting procedures or target online campaign activities, we judge that the most significant new opportunities for cyber threat actors are COVID‑19‑related narratives that can be used to undermine confidence in elections.Footnote 12 These narratives include connecting voter fraud with mail-in voting and exaggerating the public health risk of in‑person voting.Footnote 13

Key targets in the democratic process

In the 2019 Update: Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process, we identified three key enduring targets within the democratic process: voters, political parties, and elections. The following section provides additional detail on the threats faced by each target and how they have evolved in recent years, including in the context of the COVID‑19 pandemic.

Voters engage with political parties, candidates, and other voters through social media. Voters also access information about voting processes online. Cyber threat actors manipulate online information to influence voters’ opinions and behaviours.

Political parties compete for attention and support in elections, relying heavily on the Internet, which they use to organize and to communicate with voters. This reliance is even more pronounced during the COVID‑19 pandemic where traditional in‑person campaigning and fundraising events face COVID‑19‑related restrictions. Cyber threat actors use cyber tools to target the websites, emails, social media accounts, networks, and devices of political parties, candidates, and their staff. Cyber threat actors also target consultants, polling firms, and research companies hired by political parties.

Elections include all the processes involved when individuals vote for their government representatives—registering voters, casting ballots, counting ballots, and releasing results to the public. Voters must have confidence in the legitimacy of the process. Cyber threat actors could attempt to undermine trust in elections or suppress voter turnout by altering content on the websites, social media accounts, networks, and devices used by election management bodies.

Targeting voters

Figure 03: Three components of online foreign influence activity

Long description - Three components of online foreign influence activity

Online foreign influence activity is covert, conducted by foreign actors, and uses cyberspace or cyber tools. The image has three miniature people tinkering with a laptop and computer. There are error messages floating around the laptop and computer indicating something has been hacked or stolen.

We assess that the most significant cyber threat faced by voters is online foreign influence, which is when foreign actors covertly create, disseminate, or amplify false and misleading material online to influence the beliefs or behaviours of voters. Cyber threat actors also target databases of information about voters held by political parties and election management bodies as well as websites used by voters to get the information they need to vote.

Online foreign influence has become a common tool for adversaries. They use online influence to further their core interests, such as national security, economic prosperity, and ideological goals.Footnote C Online influence campaigns can try to:

- impact civil discourse;

- influence policy makers’ choices;

- compromise government relationships and the reputations of politicians;

- delegitimize the concept of democracy and other values such as human rights and liberty; and

- exacerbate existing frictions in democratic societies.

Foreign influence and the domestic information ecosystem

Voters must contend with an online information ecosystem filled with false and misleading information. This information can come from both foreign and domestic sources. It is often difficult to determine the origin of information circulating online, who is spreading it, and why. While beyond the scope of this assessment, false or inaccurate information spread by domestic actors—with or without malign intent—can negatively impact voters and contribute to the goals of foreign threat actors, such as undermining voter trust in electoral processes or increasing polarization among voters.

Types of false information: disinformation vs. misinformation

Disinformation is false information that is specifically created and disseminated to cause harm.Footnote 14 This can include altering official documents to make false claims appear legitimate or otherwise creating official-seeming content, like deepfakes.

Misinformation is false information spread without the intention to cause harm.Footnote 15 In practice, it is often difficult to distinguish between misinformation and disinformation.

Social media provides a megaphone for domestic actors with many followers, such as influencers, individuals with verified accounts, or public figures. False information promoted by these prominent figures, including narratives that undermine democratic institutions and processes, can spread farther and have greater impacts on voters than when foreign actors try to do the same thing covertly. The disproportionate reach of public figures has been observed in the context of COVID‑19. Researchers at the Reuters Institute found that although COVID‑19 misinformation from prominent public figures made up just 20% of the claims of COVID‑19 misinformation studied, they accounted for 69% of total social media engagement.Footnote 16

Some governments and political parties employ disinformation or manipulate the online information ecosystem to influence voters.Footnote 17 For example, in the run-up to the 2021 Ugandan general election, Facebook took down a network of fake and duplicate accounts that were linked to the Ugandan government and were being used to boost the popularity of posts.Footnote 18 In the following days, the government banned social media and then shut down the Internet in Uganda.Footnote 19 Governments have increasingly restricted Internet access during elections, limiting access to information, curbing dissent, and limiting freedom of expression.Footnote 20

Online influence for hire

Private firms increasingly provide online influence as a service to governments and political actors.Footnote 21 A 2020 Oxford study identified 48 cases of private companies deploying disinformation on behalf of a political actor. Since 2018, the same researchers have identified more than 65 firms offering disinformation as a service.Footnote 22 Private firms spread disinformation through trolling, automated accounts, human‑curated accounts, and AI.Footnote 23 Governments and political actors who hire firms to conduct online influence campaigns on their behalf not only use domestic firms, but also turn to firms based in other countries.Footnote 24 For example, between 2019 and 2020, the Archimedes Group, based in Israel, ran online influence campaigns against elections in Africa, Latin America, and South East Asia.Footnote 25

State‑sponsored cyber threat actors, including from Russia and Iran, have taken advantage of domestic groups and movements in other countries and used the messages and reach of these domestic groups to better influence voters.Footnote 32 For example, state‑sponsored actors have promoted content and messaging related to QAnon for the purpose of reaching voters in the US. State‑sponsored actors have also pretended to be domestic groups in the US to send threatening messages to voters.Footnote 33

Case study: QAnon and online foreign influence

QAnon is a loose cluster of debunked conspiracy theories, whose content has increased in volume and frequency since late 2017.Footnote 26 While primarily based in the US, QAnon theories have gained a following in over 25 countries, including Canada, which is one of the top four countries driving QAnon content on social media.Footnote 27 State-sponsored groups in Russia and Iran have propagated content related to QAnon.Footnote 28 Social media and news accounts tied to Russia promoted QAnon in its early days.Footnote 29 On Twitter, accounts suspected of being controlled by Russian cyber threat actors sent a high volume of tweets related to QAnon in 2019.Footnote 30 To a lesser extent, Iranian actors have used QAnon references and content in their online influence activity, including activities during the 2020 US election.Footnote 31

Domestic journalists and intellectuals have also unknowingly been hired by foreign threat actors to write articles with a political angle that are then used in broader online foreign influence campaigns.Footnote 34 This further blurs the distinction between foreign and domestic actors. Co-opting legitimate sources to endorse specific perspectives lends credibility to messages promoted by online foreign influence campaigns.

The Internet, social media platforms, and voters

Voters around the world get a substantial amount of information online, often from social media.Footnote 35 However, social media platforms are a fertile environment for creating and disseminating false information. They rely on deep learning algorithms to suggest content to their users, which often prioritize posts that have greater prior engagement (e.g., shares, likes, comments) and end up amplifying inflammatory content.Footnote 36 As a result, voters are faced with a glut of misleading, false, and inflammatory information. In the context of COVID-19 and elections, some social media platforms have instituted measures to try to address the spread of false information by:

- demoting “borderline content” (i.e., content that almost violates community guidelines);

- shutting down inauthentic accounts;

- hiring personnel to screen posts and investigate malfeasance;

- collaborating with fact‑checking and research organizations;

- flagging or demoting misleading content; and

- directing users to authoritative sources.Footnote 37

Some social media platforms, tailored to niche audiences, play a critical role in the dissemination of hate and extreme content.Footnote 38 While sites such as 4chan, 8chan, Gab, and Parler do not have the reach of larger social media companies, they provide a space for like‑minded people to interact and perpetuate extreme narratives that can spread to the rest of the Internet.Footnote 39 As more mainstream platforms increasingly remove extreme and false content, they can push individuals interested in this information from an open community, such as Twitter, into fringe environments, like Gab, that pride themselves on allowing users to post anything they like.Footnote 40 Hostile foreign actors have used these platforms for online foreign influence activity. For example, during the 2020 US election, Russian actors targeted far-right American users on Gab and Parler with online foreign influence activity that promoted President Trump and denigrated then‑candidate Biden.Footnote 41

Some platforms are used primarily by specific communities and can be used to censor or cultivate messages within those communities. For example, WeChat, a do-everything app from China used by billions around the world, has magnified divisions and spread disinformation or propaganda specific to the Chinese diaspora on the platform.Footnote 42

Online foreign influence on encrypted platforms

Encrypted messaging apps (EMAs), like WhatsApp, Signal, and Telegram, make it difficult to trace and curb the spread of false information, which is why many groups that have been de-platformed from mainstream apps are flocking to EMAs.Footnote 43 For example, after far‑right groups in the US were removed from many mainstream platforms and Parler went offline due to actions by Apple, Google, and Amazon, many far‑right users adopted EMAs like Signal, CloutHub, MeWe, Telegram, and Rumble.Footnote 44 Further, the closed nature of EMAs means that most users are communicating with people they consider trustworthy. The ability to forward information to large groups of people also increases the chances for false information to be misinterpreted as fact. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, EMAs have also become a key distribution channel for medical misinformation, hoaxes, and scams.Footnote 45

COVID-19 and the cyber threat to voters

The COVID-19 pandemic offers new opportunities for online foreign influence aimed at undermining voter confidence in electoral processes and attempting to decrease voter turnout.Footnote 46 Many jurisdictions have expanded access to mail-in ballots and other alternative voting methods to decrease the size of crowds at voting locations and protect at‑risk voters. However, this has created an opportunity for cyber threat actors to create or amplify false narratives linking mail-in voting and other alternative voting arrangements with voter fraud. Hostile foreign actors can also create and amplify messaging to increase voters’ perception of the risk of contracting COVID‑19 at voting locations in an attempt to decrease turnout. Even if turnout is not reduced, the presence of these narratives and the perception that COVID-19 decreased turnout can reduce voter confidence in the results. Finally, changes to voting procedures, such as extended voting days and expanded use of mail-in ballots, can delay the dissemination of results. This delay presents an opportunity for threat actors to spread disinformation, such as false results, before the election management body has a chance to release accurate information.

Targeting political parties

Cyber threat actors target political parties, candidates, and their staff in many countries to:

- disrupt engagement with the public for financial gain, to harm the political party or candidate, or for publicity;

- steal sensitive or proprietary information, including from databases; or

- interfere with political party procedures that are undertaken online.

We assess that cybercriminals will almost certainly continue to take advantage of the online presence of political parties or politicians for financial gain, either by hijacking the websites or accounts of political parties or politicians or by creating fake websites, accounts, or emails and other communications that are designed to look official. Cybercriminals can use ransomware or DDoS attacks to disrupt online events or pages and attempt to extort funds from politicians or political parties. According to Cloudflare, an American website security company, there was a notable amount of DDoS activity against US political campaign websites in 2020.Footnote 47 Cybercriminals can also compromise the online resources of politicians and political parties in other ways. For example, in the 2020 US election, one candidate’s campaign website was compromised by cybercriminals who attempted to use it to collect cryptocurrency.Footnote 48 In addition, some cybercriminals leverage current events, including elections, to target their victims, sending phishing emails related to topics of interest to their victims so that recipients are more likely to open malicious attachments or click malicious links.Footnote 49 In the case of election-related lures, these victims can be members of political parties, candidates, their staff, voters, or other individuals interested in the election.

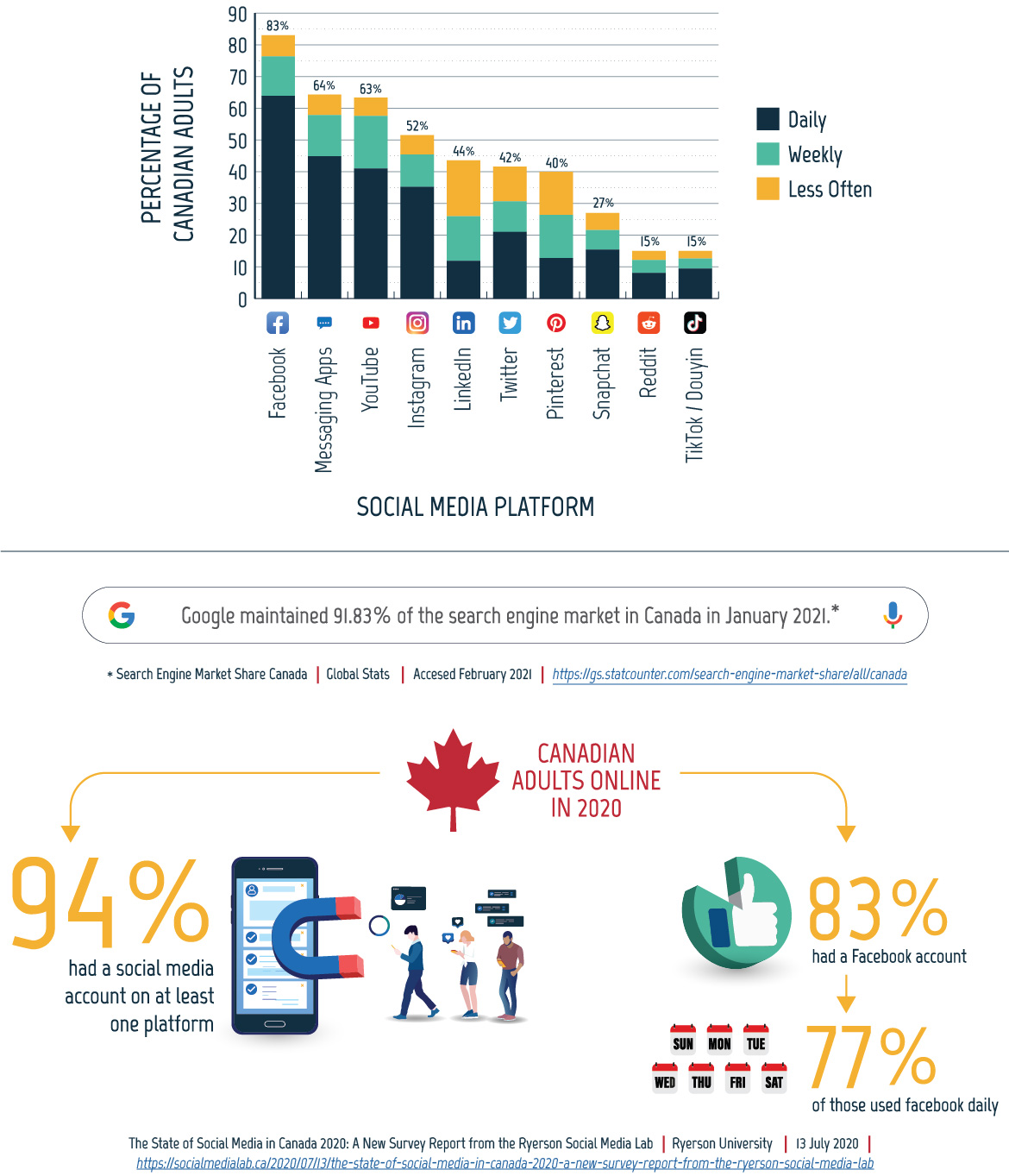

Figure 04: Political campaigning during the COVID-19 pandemic

Long description - Political campaigning during the COVID‑19 pandemic

A review of national elections in 51 countries held during the COVID‑19 pandemic in 2020 found that 22 of the 51 countries had COVID‑19 restrictions that limited opportunities for public gatherings, impacting political campaigns. In many countries candidates responded by campaigning online.

This is accompanied by an image of 51 ballot boxes, with 22 highlighted.

This information comes from: Erik Asplund, et al. “Elections and COVID‑19: How election campaigns took place in 2020.” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. 2 February 2021. https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/elections-and-covid-19-how-election-campaigns-took-place-2020.

State-sponsored actors are also interested in the networks, websites, and email and social media accounts of political parties, candidates, and their staff. Disrupting the campaign of a candidate or political party could influence support for that party or undermine confidence in the fairness of the electoral process. Hacktivists, politically motivated actors, and thrill-seekers have also targeted the websites and events of political parties and candidates to spread their own messages as well as for publicity.Footnote 50

In addition, sensitive information related to a political party or candidate as well as databases of personal information held by political parties are attractive to both cybercriminals and state-sponsored actors. Polling firms, research companies, and consultants that are hired by political parties or candidates also have information of interest to cyber threat actors. Stolen databases can be used for future cyber activity, including financially motivated activity as well as strategically motivated campaigns by state-sponsored cyber threat actors. Sensitive information stolen from compromised accounts can be leaked to tarnish the reputation of a candidate or used for extortion. Threat actors can focus online foreign influence activities against a specific candidate or party, attempting to drive voters away from that candidate and towards the opposition.

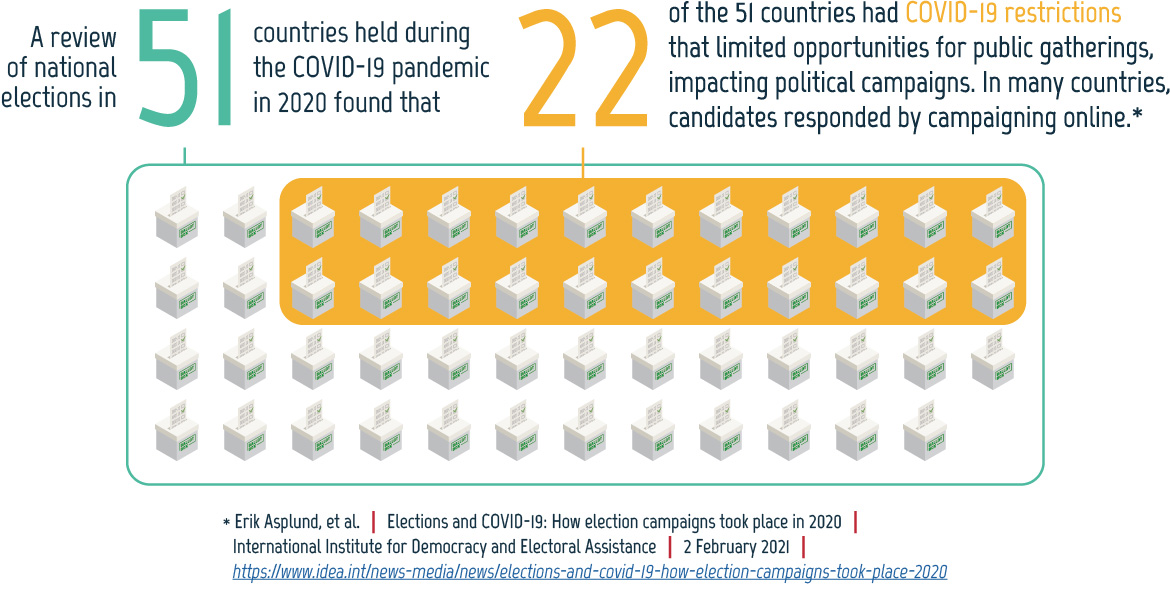

Figure 05: How candidates adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic

Long description - How candidates adapted to the COVID-19 pandemic

Figure describes how candidates campaigned in four different countries.

United States, November 2020: The two major parties held their conventions online.*

Kuwait, December 2020: Candidates used Twitter, Zoom, WhatsApp, YouTube, TV, and phone calls extensively in place of in-person meetings.*

Singapore, July 2020: Political parties held e-rallies on Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, TV, and radio.*

South Korea, April 2020: Political parties used social media, texts, and cell phone applications. Some candidates used augmented reality to engage with supporters remotely.*

The text describing each country is accompanied by the country’s flag and map.

* This information comes from: Erik Asplund, et al. “Elections and COVID-19: How election campaigns took place in 2020.” International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. 2 February 2021. https://www.idea.int/news-media/news/elections-and-covid-19-how-election-campaigns-took-place-2020.

Finally, some political parties vote online. In some cases, this allows more party members to vote in leadership races.Footnote 51 However, having these votes online makes them vulnerable to cyber threat actors who may want to change the results or sow distrust within a political party. In 2021, a German political party that held its leadership vote online during a virtual party conference was targeted by a DDoS attack. The attack interrupted the conference, but the vote was not impacted because it was intentionally hosted on a different server to protect the vote from cyber threat activity.Footnote 52

COVID-19 and the cyber threat to political parties

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in-person campaigning events, such as political rallies, fundraisers, or door-to-door canvassing, have been restricted or banned in some jurisdictions. In response, some political parties and candidates have adapted to comply with local public health restrictions through mailing information packages, car rallies, distanced door-to-door canvassing, and increasing their use of online tools for campaigning or taking internal party decisions.Footnote 53 Since the start of the pandemic, political parties have held virtual conventions, town halls, fundraisers, and turned to online video calling to canvas voters.Footnote 54 Election campaigning and fundraising had been moving online before COVID-19, but the pandemic has increased the use of digital tools.Footnote 55 This movement towards online solutions creates more opportunities for cyber threat actors interested in targeting political parties and campaigns to advance strategic goals or for financial gain and makes campaigns less resilient if online resources are compromised.

Adapting electoral campaigns in COVID-19: South Korea

South Korea was one of the first countries to hold a major national election during the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions on holding events, attending public gatherings, and social distancing requirements prevented conventional campaign activities like rallies, public speeches, debates, fundraising events, and door-to-door canvassing. Instead, candidates shifted to online and digital technology such as video messages disseminated via social media, texts, and mobile phone applications. Some candidates used augmented reality to engage with supporters remotely. Some candidates also campaigned outside the digital sphere, participating in COVID-19-related volunteer work and mailing printed materials to voters.Footnote 56

Targeting elections

Cyber threat actors interested in undermining democratic institutions or sabotaging election results can target electoral processes and infrastructure, altering content on the websites and social media accounts of election management bodies, stealing information such as voter registration databases, or compromising the systems or communications underlying the election. Election processes around the world involve four main steps, and each can introduce opportunities for cyber threat actors.

Voter registration is done online in many jurisdictions globally.Footnote 57 Cyber threat actors can target online voter registries to attempt to add fake voter records, erase or encrypt the data, make the website inaccessible for registration, or display misleading information. These activities can sow doubt in the minds of voters, slow down voting, cause voter frustration or suppression, and impact election results. Stolen voter registration data can be used for future threat activity, including strategic activity related to the election as well as cyber threat activity completely unrelated to the election.Footnote D

When voters go to cast their ballots in person, their identities must be checked against the list of registered voters contained in poll books. Electronic poll books are used in many countries to make it easier to look up voters. In some cases, these poll books are networked so that different locations can communicate with each other to allow people more flexibility when choosing where to vote while preventing people from voting at more than one location. However, connecting these devices and enabling them to communicate remotely increases their vulnerability to cyber threat activity. After a voter’s identity is checked against the list of registered voters, they can cast their ballot. In almost all cases, this step is paper based or electronic. Estonia is the only country that uses Internet-enabled voting for all jurisdictions in national-level elections.Footnote 58

Once ballots are cast, they must be counted and the results disseminated. Ballots are often counted electronically, but the results can also be tabulated by hand. The results of the count must then be submitted to a central body that tallies the numbers from different polling locations and jurisdictions. The results can be submitted via phone, fax, email, or electronically. However, many jurisdictions retain paper records to enable the results to be validated or audited. The final stage of the voting process is the dissemination of the results, which is frequently done over the Internet.

Most election management bodies use some degree of technology to improve their electoral processes (e.g., standard office tools and websites, biometric voter registration databases, and Internet-enabled voting systems).Footnote 59 These solutions can increase efficiency, accuracy, and transparency, but each component of the election process that is online or electronic could be targeted by cyber threat actors. The institutions responsible for elections implement a range of measures to protect the electoral process, such as keeping crucial parts of the process paper based, maintaining back-ups of important databases, and establishing alternative procedures to allow voters to cast their ballots if the technology involved in the process malfunctions or is compromised.

After some elections, cyber threat actors have conducted operations to discredit or undermine the elected government before it takes office. These efforts do not necessarily target voters, political parties, or elections. In many cases they target government institutions broadly or even critical infrastructure. Threat actors can also spread disinformation after an election to undermine trust in the results or attempt to stop the elected government from taking office.

Case study: Cyber protests in Belarus

The August 2020 presidential election in Belarus has been condemned as fraudulent by many countries, including Canada, the US, and the European Union (EU).Footnote 60 Following the count, the opposition refused to concede the election, triggering widespread protests.Footnote 61 In this context, hacktivists in Belarus used various tactics, including defacing government websites and targeting government institutions, to pressure the incumbent president into resigning. In one instance, hacktivists leaked the identities and addresses of 1,000 law enforcement officers who were violently responding to protesters.Footnote 62 In August 2020, hacktivists were responsible for at least 15 cyber incidents against state-owned online resources in Belarus.Footnote 63

COVID-19 and the cyber threat to elections

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, some parts of the election process, like voter registration, were moving online in many jurisdictions. However, very few jurisdictions were attempting to implement Internet-enabled voting at the national-level prior to the pandemic, and it is unlikely that countries that do not already have online voting systems in place would be able to or inclined to implement Internet-enabled voting at the national-level in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.Footnote 64

There have been some adjustments in response to COVID-19 for national-level elections worldwide, in particular new hygiene and public health requirements, changes to voting hours and registration deadlines, and additional voting options for at-risk populations and those in isolation. While most of these changes do not themselves create new cyber security threats, they must be communicated clearly to voters so that voters can take advantage of the changes and remain confident that their election remains free and fair.Footnote 65 Some democracies have relied on the Internet, email, and text messages to communicate these changes, and cyber threat actors can target these communications—disrupting them, modifying them, or disseminating false information designed to look authentic.Footnote 66

Disruptions from increased demand

Besides threat activity, online resources related to voting and elections, such as information pages, voter registration databases, and absentee ballot request portals, may face a higher than usual demand due to the pandemic. If not mitigated, such an increase could impede access to the resources voters need to participate in an election. This was a concern expressed by election officials in the US prior to their 2020 election.Footnote 67 However, we have not seen widespread outages due to higher-than-usual demand.

In addition, like many during the pandemic, some election management bodies have been forced to work remotely as they prepare for elections. Unless using cyber security best practices, remote work arrangements could introduce additional vulnerabilities as individuals access sensitive data related to their work over home Wi-Fi networks that are often poorly secured in comparison to corporate IT infrastructure.

Global trends

Global baseline of known events

Since the 2019 Update: Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process, the Cyber Centre has continued to monitor cyber threat activity against democratic processes around the world. Consistent with our previous reports, we assume that our combined data sources underestimate the total number of events targeting democratic processes around the world. Based on our observations from 2015 to 2020, we have identified four trends.

Trend 1 — State-sponsored cyber threat activity focuses on specific states and regions

We assess that state-sponsored actors with ties to Russia, China, and Iran are responsible for the majority of cyber threat activity against democratic processes worldwide. Since 2015, over 90% of the cyber threat activity against democratic processes we observed by these states focused on countries of strategic significance to them. Specifically, most of the observed cyber activity targeting democratic processes attributed to Russia targeted the US, Ukraine, and other European states. Most of the cyber activity attributed to China targeted the US, Taiwan, and other countries in Asia and the Pacific. For Iran, most of this type of activity was against the US. The focus of state-sponsored threat activity against democratic processes is dictated by the specific interests of the threat actors and the states these actors perceive as threats to their regional and global objectives.

Figure 06: Cyber threat actors target strategically significant states and regions

Long description - Cyber threat actors target strategically significant states and regions

Since 2015, over 90% of the cyber threat activity against democratic processes we observed by Russia, China, and Iran targeted states and regions of strategic significance to them.

This is accompanied by a map of Russia pointing to Europe and the US, map of Iran pointing to the US, and map of China pointing to Asia Pacific and the US.

Trend 2 — Most cyber threat activity against democratic processes supports strategic objectives

Figure 07: Strategic and incidental objectives

Long description - Strategic and incidental objectives

Strategic:

- State‑sponsored adversary with geopolitical motivation

- Hacktivists with ideological motivation

- Politically motivated actors motivated by power

- Terrorist groups motivated by ideological violence

Incidental:

- Cybercriminals motivated by profit

- Thrill-seekers motivated by satisfaction

From 2015 to 2020, the vast majority of cyber threat activity affecting democratic processes around the world has been carried out to advance the strategic objectives of the threat actor. State‑sponsored actors conducted 76% of the observed cyber threat activity against democratic processes for which we have an attribution. Given the potential payoff and relative ease of such an operation, we assess that state‑sponsored cyber actors very likely have a greater interest in targeting democratic processes than other cyber actors. Incidental activity refers to cyber activity that impacted a democratic process but was not conducted to advance a strategic goal. Cyber threat activity by cybercriminals was the most common type of incidental activity, representing 8% of the observed cyber activity against democratic processes for which we have an attribution.

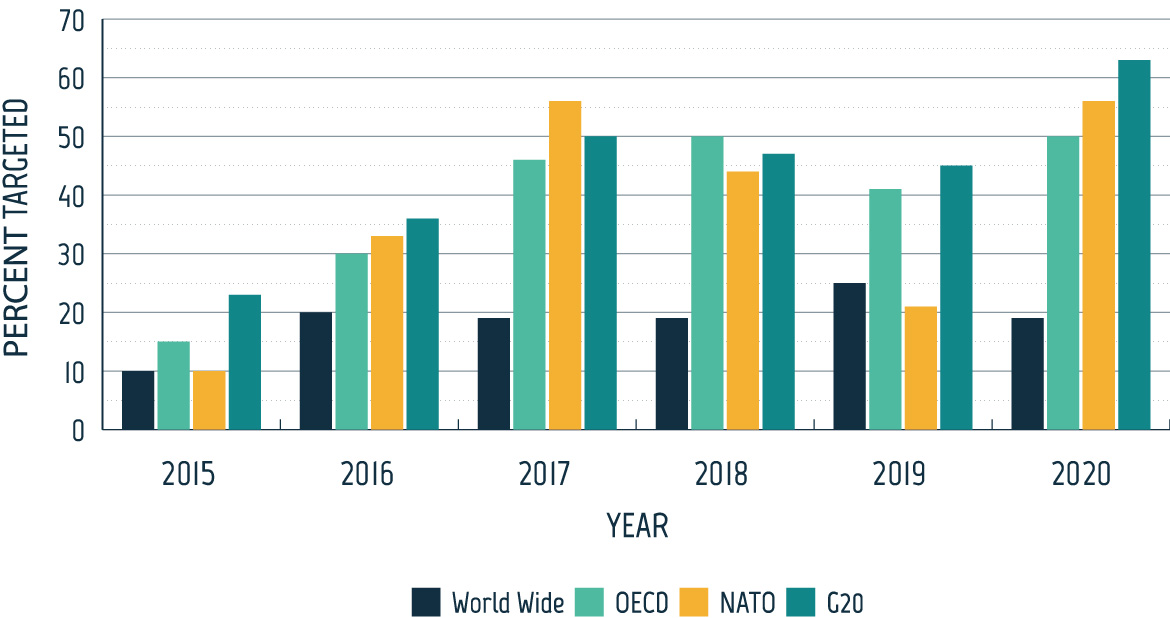

Trend 3 — Targeting of democratic processes remains high

Consistent with our previous reporting, cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes remains high. After a steep increase in the proportion of elections targeted by cyber threat activity from 2015 to 2017, the proportion of democratic processes targeted by cyber threat activity related to worldwide elections, elections of OECD countries, and elections of G20 countries remained relatively stable from 2017 to 2020. These numbers do not include cases where domestic actors engaged in covert online influence activities within their own countries or where public relations firms were hired to conduct this type of activity. These firms have operated in at least 48 countries.Footnote 68

Although the percentage of elections that have been targeted each year has remained stable since 2017, these statistics do not capture variations in the amount of cyber activity experienced by each country—extensive cyber campaigns against one country and a single cyber event against another are each counted as one country targeted.

There are also countervailing trends that act to decrease the level of cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes. These trends include:

- efforts by social media companies to identify and remove accounts engaging in coordinated inauthentic behaviour online as well as flagging problematic content;

- greater media coverage and public awareness;

- mobilization of government bodies, non-governmental and research organizations, and civil society to counter false content;

- improved cyber security practices; and

- public attribution and legal indictments against threat actors.

Although there has yet to be a systematic study of the effectiveness of these practices, a comparison of the 2016 and 2020 US elections suggests that identifying and publicizing potential online foreign influence campaigns, strengthening the cyber security postures of organizations involved in the election, and improving social media companies’ responses to malicious activity on their platforms can decrease the impact of hostile states’ efforts to influence democratic processes through cyber means.Footnote 69 Taiwan’s 2020 election also provides evidence that government investigations, civil society mobilization to counter false information, and social media company responses can mitigate foreign influence activity and protect democracy.Footnote 70

Figure 08: Cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes related to an election

Long description - Cyber threat activity targeting democratic processes related to an election

Bar chart with the following values:

| Year | Percentage of World Wide Elections Targeted | Percentage of OECD Elections Targeted | Percentage of NATO Elections Targeted | Percentage of G20 Elections Targeted |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 10% | 15% | 10% | 23% |

| 2016 | 20% | 30% | 33% | 36% |

| 2017 | 19% | 46% | 56% | 50% |

| 2018 | 19% | 50% | 44% | 47% |

| 2019 | 25% | 41% | 21% | 45% |

| 2020 | 19% | 50% | 56% | 63% |

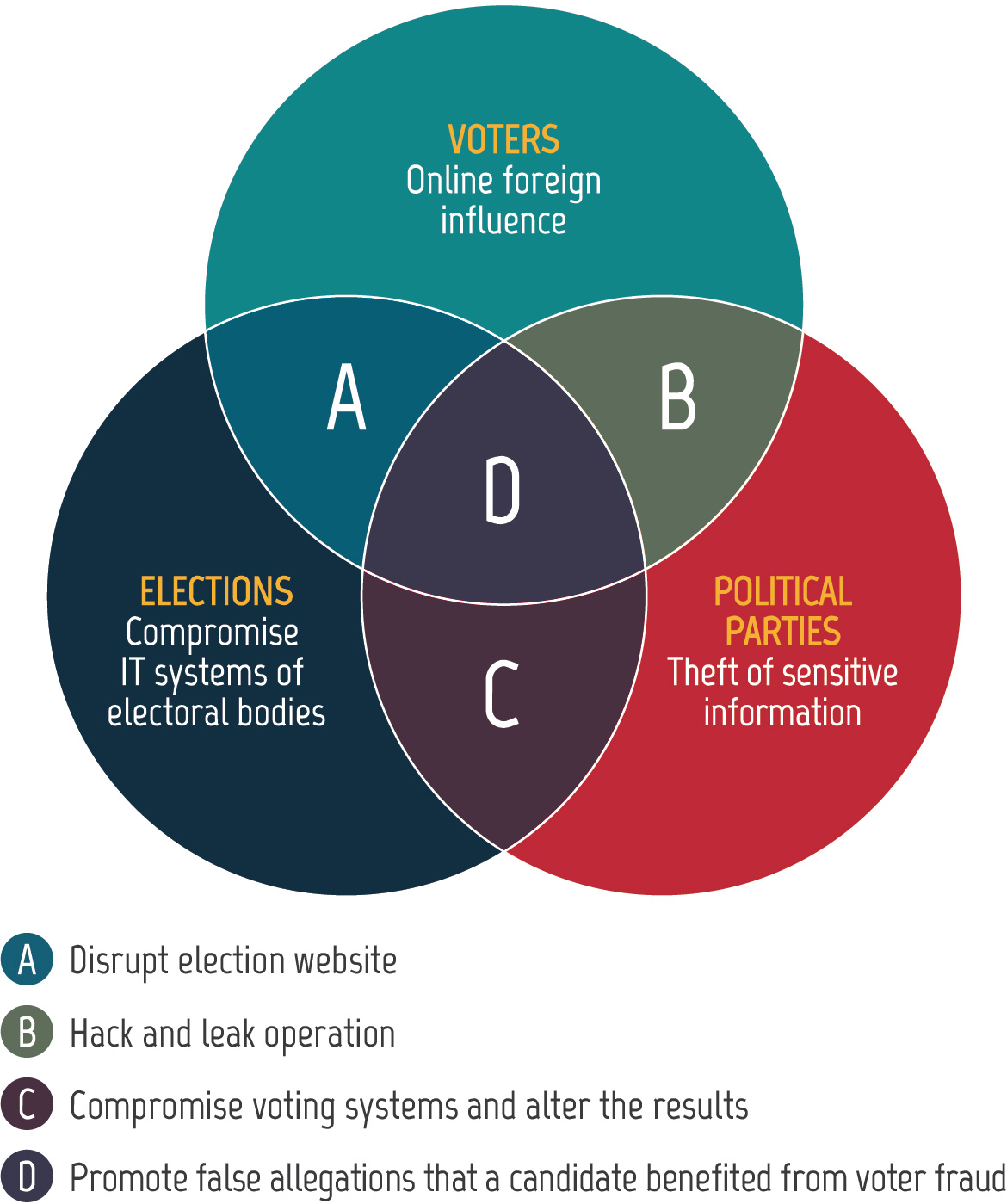

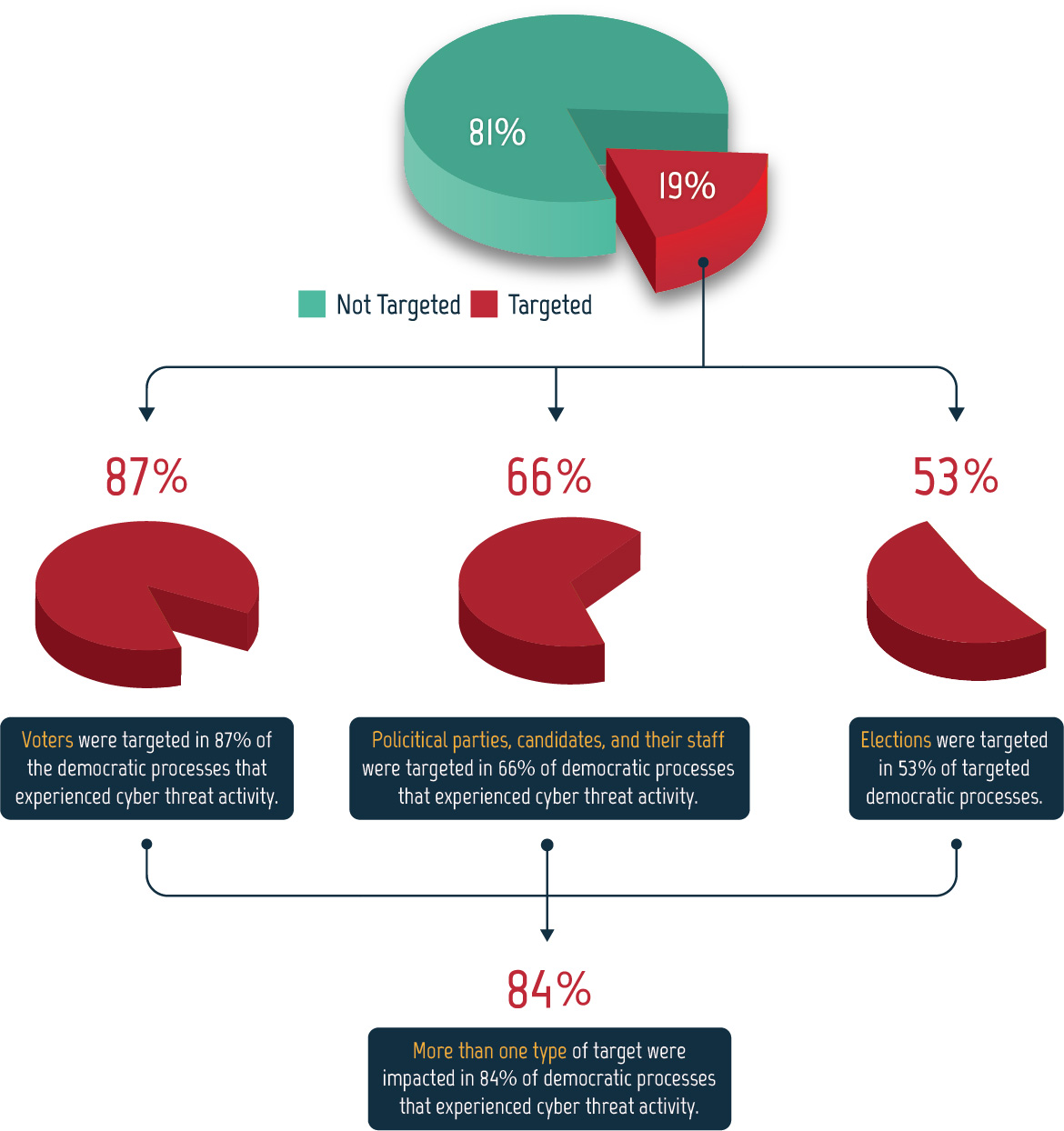

Trend 4 — Cyber activity frequently impacts multiple targets within the democratic process

Between 2015 and 2020, approximately one fifth of the democratic processes we studied were targeted by cyber threat activity. Of this, the majority (84%) experienced threats to more than one type of target—voters, political parties, and elections. In some cases, one incident impacted multiple types of targets, like a hack-and-leak operation that targets both a candidate and the voters exposed to the information.

Voters were victims more often than political parties and elections, being implicated in 87% of the surveyed democratic processes that experienced cyber threat activity from 2015 to 2020. Often voters were targeted in combination with political parties, elections, or both. Political parties were the second most common target after voters at 66%, followed by elections in third at 53%.

Figure 10 demonstrates that voters are targeted most often and that they are often targeted in conjunction with political parties, elections, or both. As a result, we assess that it is likely that cyber threat actors perceive targeting voters to be a more effective or efficient way to interfere with democratic processes or that targeting a combination of voters, political parties, and elections is more effective than targeting one group in isolation.

Figure 09: Cyber threat activity can impact multiple targets

Long description - Cyber threat activity can impact multiple targets

Venn diagram with three circles with examples of cyber threat activity targeting voters, elections, political parties, and combinations of the three.

Voters - Online foreign influence

Political Parties – Theft of sensitive information

Elections – Compromise of IT systems of electoral bodies

Voters and Political Parties – Hack and leak operation

Voters and Elections – Disrupt election website

Political Parties and Elections – Compromise voting systems and alter the results

Voters, Political Parties, and Elections – Promote false allegations that a candidate benefited from voter fraud

Figure 10: Democratic processes related to elections targeted worldwide, 2015-2020

Long description - Democratic processes related to elections targeted worldwide, 2015-2020

Pie chart showing that 19% of elections were targeted and 81% of elections were not. Of the 19% that were targeted

- Voters were targeted in 87% of the democratic processes that experienced cyber threat activity.

- Political parties, candidates, and their staff were targeted in 66% of democratic processes that experienced cyber threat activity.

- Elections were targeted in 53% of targeted democratic processes.

Multiple types of targets were often impacted—more than one type of target were impacted in 84% of democratic processes that experienced cyber threat activity.

Canadian context

Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process

Canada experiences only a fraction of the cyber activity we have observed targeting other democratic processes around the world. The Canadian federal election remains paper based, and Elections Canada has a number of legal, procedural, and IT measures in place that provide very robust protections against attempts to covertly manipulate election results in Canada.

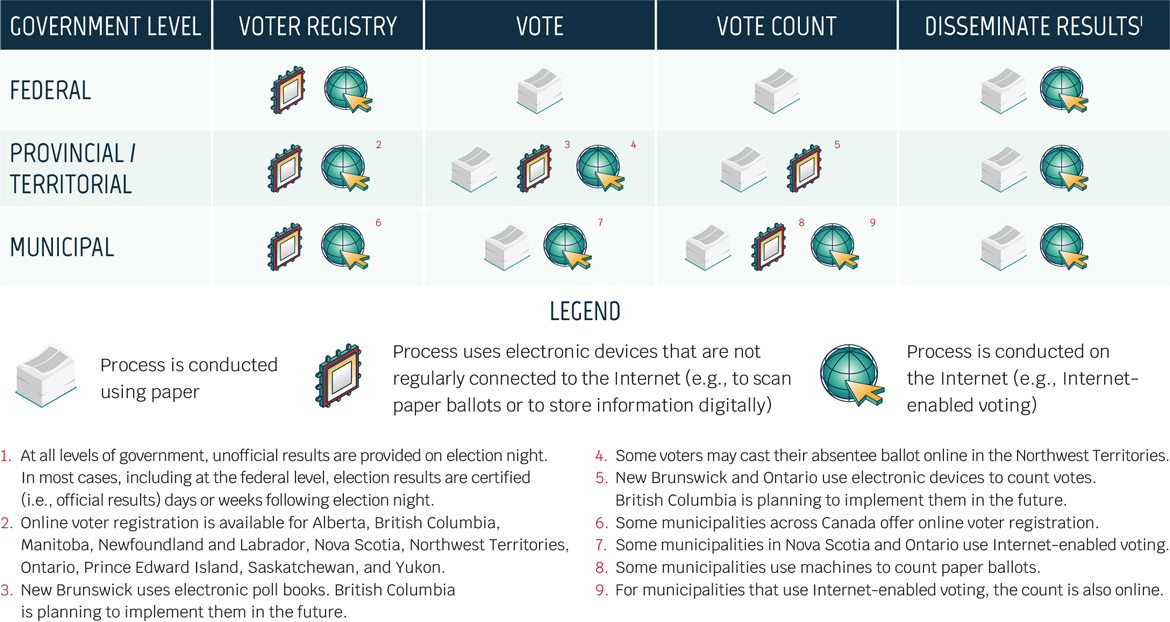

Although federal elections in Canada are paper based, in sub-national elections, Canada is leading adoption of Internet-enabled voting, with some municipalities in Ontario and Nova Scotia adopting the technology and the Northwest Territories allowing absentee ballots to be cast online. At the national level, however, Canada continues to use paper ballots. See Figure 11 for an update on how elections are run at the federal, provincial/territorial, and municipal levels in Canada.

In addition, political parties at the national and provincial levels have voted online to select party leadership.Footnote 71 However, having these votes online makes them vulnerable to cyber threat actors who may want to change the results or sow distrust within a political party.

Figure 11: Technology in Canadian elections

Long description - Technology in Canadian elections

| Government level | Voter Registry | Vote | Vote count | Disseminate resultsTable note 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Federal | Electronic, Online | Paper | Paper | Paper, Online |

| Provincial/Territorial | Electronic, OnlineTable note 2 | Paper, Electronic,Table note 3 OnlineFootnote 4 | Paper, ElectronicTable note 5 | Paper, Online |

| Municipal | Electronic, OnlineTable note 6 | Paper, OnlineTable note 7 | Paper, Electronic,Table note 8 OnlineTable note 9 | Paper, Online |

- Paper – Process is conducted using paper

- Electronic – Process uses electronic devices that are not regularly connected to the Internet (e.g., to scan paper ballots or to store information digitally)

- Online – Process is conducted on the Internet (e.g., Internet-enabled voting)

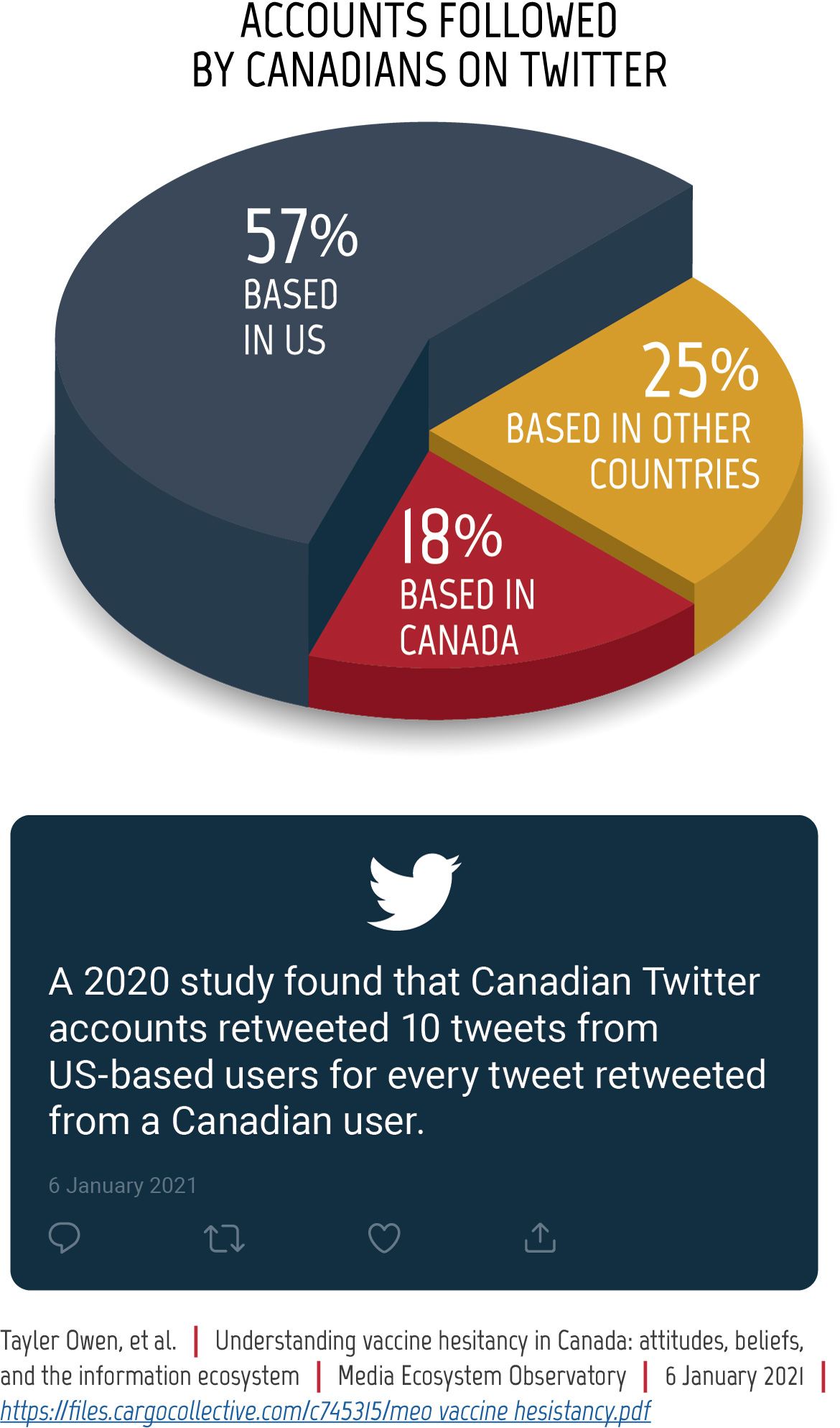

We assess that Canada remains a lower-priority target for online foreign influence activity relative to some other countries. However, Canada’s media ecosystem is closely intertwined with that of the US and other allies, which means that when their citizens are targeted, Canadians become exposed to online influence as a type of collateral damage. In 2020 and early 2021 we have seen how disinformation and misinformation that gain traction in the US and in other allied countries can impact Canadians.

In 2019, the Critical Election Incident Public Protocol (CEIPP) was established as the mechanism for communicating with Canadians in a clear, transparent, and impartial manner if there had been an incident that threatened Canada’s ability to have a free and fair election.Footnote 72 No threats met the CEIPP’s high threshold for public announcement during the 2019 General Election, but the panel responsible for making that determination was prepared to intervene if needed. In addition, other mitigation measures were put in place, including efforts to protect voters, political parties, and elections. See Figure 13 for examples of these measures.

Figure 12: Canadians on Twitter

Long description - Canadians on Twitter

Accounts followed by Canadians on Twitter (Pie Chart)

- 57% based in the US

- 18% based in Canada

- 25% based in other countries

A 2020 study found that Canadian Twitter accounts retweeted 10 tweets from US-based users for every tweet retweeted from a Canadian user.

Information from: Tayler Owen, et al. “Understanding vaccine hesitancy in Canada: attitudes, beliefs, and the information ecosystem.” Media Ecosystem Observatory. 6 January 2021. https://files.cargocollective.com/c745315/meo_vaccine_hesistancy.pdf.

Figure 13: Measures to protect Canada's democratic process

Long description - Measures to protect Canada's democratic process

Critical Election Incident Public Protocol

- Mechanism for communicating with Canadians if an incident were to occur that threatens Canada’s ability to have a free and fair election

Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections Task Force

- Comprised of officials from CSE, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Global Affairs Canada, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police

Cyber Centre Advice and Briefings

- Hotline with Elections Canada

- Briefings with political parties

- Cyber security resources for the public

Efforts of Elections Canada

- Improved cyber security posture

- Monitored information environment

- Corrected false or misleading information about electoral process

Agreements with Social Media and Technology Companies

- Canada Declaration on Electoral Integrity

Digital Literacy

- Digital Citizen Initiative

- Digital Citizen Research Program

- Public Policy Forum Digital Democracy Project

COVID‑19 and the outlook for democratic processes in Canada

Elections Canada has implemented measures to increase the capacity and convenience of the vote-by-mail system to meet a potential increase in demand and has indicated that an increased volume of mail-in ballots could delay the release of election results.Footnote 73 Some of these changes, such as allowing more voters to apply online to vote by mail or incorporating optical character recognition to help read some identification documents, increase the cyber threat surface. However, these changes are based on pre-existing systems, are being carefully tested and validated prior to implementation, and include a human fallback when needed. Therefore, we assess that, on balance, these changes do not substantially change the cyber threat to Canada’s democratic process, especially as Canada remains a lower‑priority target compared to other states and has a broad set of mitigations in place to defend Canadian elections.

COVID‑19‑related changes to Canadian elections, such as an increase in voting by mail or changes to voting locations, offer additional avenues for online foreign influence, providing opportunities for cyber threat actors to spread false information related to electoral processes and results. We assess that it is very likely that false information connecting voting by mail to voter fraud will circulate in Canada in relation to the next federal election. However, we assess that these false narratives will almost certainly be less prominent and less influential than they were in the US during their 2020 election.

The Cyber Centre has procedures in place to counter fraudulent attempts to imitate the Government of Canada online. Since March 2020, the Cyber Centre has worked with partners to take down more than 8,600 websites, social media accounts, and email servers impersonating the Government of Canada.

As discussed in the NCTA 2020, COVID‑19 has pushed many organizations to remote work, adding additional vulnerabilities. While Elections Canada has also shifted its operations toward a work-from-home posture, including delivering training related to the election online, we assess that it is unlikely that sensitive information held by Elections Canada will be compromised by cyber threat actors and very unlikely that cyber activity will disrupt critical voting infrastructure. As mentioned above, Canadian federal elections are paper based, with robust defences in place to ensure the legitimacy of the results.

Case study: Canadian provincial elections during the COVID‑19 pandemic

In 2020, the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, British Colombia, and Saskatchewan held elections during the COVID‑19 pandemic. While all four experienced a slight dip in turnout, they logged record numbers of mail‑in votes and online registrations. Each province made changes to how the vote was conducted to ensure voters could vote safely, such as implementing public health and sanitary measures at polling stations, adding additional voting days and voting locations, providing additional safe and accessible voting opportunities to at‑risk voters and communities, and ensuring voters who could not physically go to a polling station could still cast their ballots. All four provinces also provided guidance to political parties and candidates about how to campaign safely during the COVID‑19 pandemic. Several political parties held virtual town halls, increased digital and mail-in advertising, and relied heavily on canvassing via phone.Footnote 74 Candidates also engaged in physically distanced in-person campaigning.Footnote 75 Despite this increased reliance on technological tools and the online space, there was no evidence of sophisticated online foreign influence campaigns or cyber activity targeting voters, political parties, or the elections themselves.

If the next Canadian federal election happens before the COVID‑19 pandemic is over, Canadian political parties and candidates will almost certainly conduct more campaign activities online and use more online tools than in the past. We assess that it is very likely that the online activities of political parties and candidates will be targeted by cyber threat activity. We assess that this activity is very unlikely to be part of a sophisticated cyber campaign against a particular Canadian political party or candidate.

Consistent with our judgement in the 2019 Update: Cyber threats to Canada’s democratic process, we assess that an increasing number of threat actors have the cyber tools, the organizational capacity, and a sufficiently advanced understanding of Canada’s political landscape to direct cyber activity against future Canadian federal elections, should they have the strategic intent. We judge it very likely that Canadian voters will encounter some form of foreign cyber interference ahead of, and during, the next federal election. However, we consider foreign interference on the scale of state-sponsored activity against US elections to be improbable in Canada at this time.

Conclusion

Canada remains a lower-priority target for cyber threat activity targeting its democratic process relative to some other countries. However, we judge it very likely that Canadian voters will encounter some form of foreign cyber interference ahead of, and during, the next federal election, although it is unlikely to be at the scale seen in the US.

The COVID‑19 pandemic has altered democratic processes and has affected how elections are held, bringing changes that may extend beyond the duration of the pandemic. Some of these changes have increased the threat surface available to cyber threat actors. COVID‑19 has also created new narratives that can be used by threat actors to undermine the perceived legitimacy of an election or weaken trust in democratic institutions, such as narratives falsely linking mail-in voting and voter fraud.

This assessment focuses on online foreign influence against democratic processes, but it is important to note how pervasive falsehoods on social media and in the domestic information ecosystem create opportunities that foreign cyber threat actors can exploit to covertly disseminate disinformation.

The Government of Canada’s Security and Intelligence Threats to Elections (SITE) Task Force, comprised of officials from CSE, the Canadian Security Intelligence Service, Global Affairs Canada, and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, continues to help the government assess and respond to foreign threats to Canada’s electoral process.

The Cyber Centre provides cyber security advice and guidance to all major political parties, in part through a Cyber Security Guide for Campaign Teams, and works closely with Elections Canada to protect its infrastructure. The Cyber Centre has also published Cyber Security Guidance for Elections Authorities and a Cyber Security Playbook for Elections Authorities.

We encourage Canadians to consult the Cyber Centre’s Focused Cyber Security Advice and Guidance During COVID-19. CSE’s Get Cyber Safe campaign will also continue to publish relevant advice and guidance to inform Canadians about cyber security and the steps they can take to protect themselves online.